On 14 October, Pope Francis will declare Archbishop Oscar Romero a saint, along with Pope Paul VI and several other beati. Martin Maier SJ, who has a longstanding connection with El Salvador, traces Romero’s personal transformation up to the moment of his martyr’s death in the middle of a sermon.

It has been a beatification and canonisation process dogged with obstacles and delays. In El Salvador, the vast majority of the population began venerating Archbishop Oscar Romero as a saint a long time ago. The impact of his murder during the celebration of Mass on 24 March 1980 was still fresh when the Brazilian Bishop Pedro Casaldáliga wrote his famous poem, ‘San Romero de América’.[1] It includes the line, ‘no one shall silence your final homily’. Yet members of the political elite in El Salvador set every possible wheel in motion to prevent any official recognition of Romero by the Church. They had allies among some influential cardinals in the Vatican curia. Romero, they argued, had not died for the faith, but because he had interfered in politics.

Pope Francis has made the beatification and canonisation of Oscar Romero a very personal priority. For the pope, Romero is a martyr and a bishop who exemplifies what it is to be a poor Church for the poor. It was only a few weeks after Francis’ election that he had a meeting with Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, the man responsible for Romero’s cause, and challenged him to ‘unblock’ the process and to move it on quickly. On 18 August 2014, while speaking to journalists on a plane on the journey back from Korea to Rome, he described Romero as a martyr for the love of neighbour, who had died for justice. The beatification took place on 23 May 2015 in El Salvador. On 30 October 2015, in a memorable address to a delegation of 500 Salvadorans, the pope said that the martyrdom of Romero had continued even after his death. Romero was ‘defamed, slandered, dragged through the mud’ – even among his fellow priests and bishops. And Pope Francis himself had witnessed this. ‘How often does this happen? People who have already given up their lives, who are already dead, are pelted still more with the hardest stone in the world, the tongue.’

On 14 October 2018, Pope Francis will canonise Archbishop Oscar Romero in Rome, together with Pope Paul VI, during the Synod on Young People, the Faith and Vocational Discernment. Alongside them, Maria Katharina Kasper, founder of the Dernbach Sisters (1820-1898), the Italian priests Francesco Spinelli (1853-1913) and Vincenzo Romano (1751-1831), Nazaria Ignazia March Mesa from Spain, founder of a religious order (1889-1943), and the Italian Nunzio Sulprizio, who died at the age of 19 (1817-1836), will all be added to the roll of the saints.

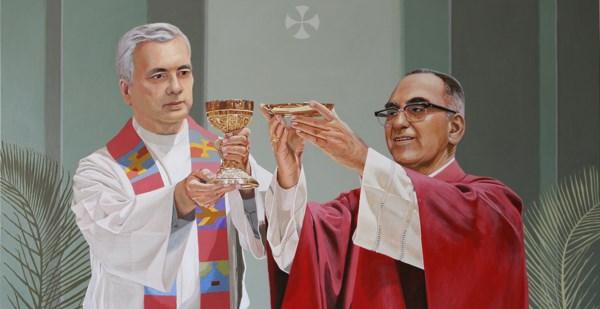

There are many points of connection between Oscar Romero and Paul VI. Paul VI guided the Second Vatican Council to its conclusion, and Archbishop Oscar Romero became one of the most important interpreters of the council for the Latin American context. The opening up to the modern world that marked the council became, for the Church in Latin America, an opening up to the world of the poor. This was expressed programmatically in the ‘preferential option for the poor’ to which the Latin American Bishops Conferences in Medellín (1968) and Puebla (1979) committed themselves. It was also Paul VI who appointed Romero as an auxiliary bishop in 1970, as bishop of the Diocese of Santiago de María in 1974, and as archbishop of San Salvador in 1977.

The relationship between Oscar Romero and Paul VI was marked by great affection. After the first complaints against Romero’s prophetic stand on justice had already reached Rome, he had a meeting with Paul VI in the course of an official visit, who showed him great understanding and kindness.[2] What was of special significance for him was that the pope blessed a picture of Rutilio Grande SJ, the first priest to be murdered in El Salvador. Romero had his last meeting with Paul VI in 1978, a few weeks before the pope’s death. On his next visit to Rome, he visited Paul VI’s grave. Its simplicity brought home to him ‘the new style of simplicity and humility in the service of the Church’ that Paul VI had left as his mark.[3]

The story of a great transformation

Oscar Romero’s story is one of a great personal transformation. Some would even call it a conversion.[4] He was born into a poor family, and was twelve years old when the desire to become a priest stirred in him. Thanks to a scholarship, he was able to study theology in Rome, which was where he was ordained priest in 1942. Back in El Salvador, he became a widely appreciated pastor. However, he was considered a conservative and wanted to keep the Church apart from the growing social unrest. When he was named archbishop, this was a disappointment for all those who had been hoping that the social engagement that had characterised the approach of his predecessor, Archbishop Luis Chávez y González, would be continued.

Nevertheless, Romero was deeply shaken when the Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande was murdered, along with two others who were with him, at the instigation of the major landowners. Grande, as parish priest, had encouraged the peasant farmers in the village of Aguilares to organise themselves and lobby for a more equitable distribution of land. Romero was a friend of his, though he distanced himself from the way Grande went about his pastoral work. Now, as he stood with the three bodies in front of him, the blood still fresh, Romero sensed that he would have to walk the same path as Rutilio. Within a few weeks, he had become that eloquent advocate for the poor. Romero’s successor, Archbishop Arturo Rivera y Damas put it powerfully: ‘a martyr gave another martyr the gift of life’.[5]

In the context of this complete change, many have spoken about ‘the Romero miracle’ and attribute it to the death of Rutilio Grande and his two companions. Where before he had been shy, even anxious, and more at home with books, so now Romero went out of his way to meet people. ‘A bishop always has a lot to learn from his people,’ he used to say, and set off for the parishes in the slums of San Salvador and in the countryside. This meant arduous journeys on foot to far-flung hamlets in tropical heat; it meant sharing the meagre food of the poor, suffering with them under the insecurity and constant threat from the military government. He set up a cafeteria in the archbishop’s offices, so that those who called could meet and talk with one another. Whenever he was able, he sat down with them and joined in their conversations.

Though he had never before quoted the documents from the Bishops’ Conference in Medellín, now they became one of the most important sources for his sermons and his pastoral letters. Where before he had sought advisers from the circles of Opus Dei, now he worked most closely with precisely those whom he had, a few years before, regarded as suspect and had given a bad name in Rome. The rich, who before had been his friends, now, by and large, rejected him. We can read in his diary on 21 August 1979 after celebrating Mass: ‘At this Mass, I had a difficult encounter with a lady who said I wasn’t the same as I used to be, that I had betrayed her. I absolutely refused to respond. I fully realise that this slander comes from all those who do not like it when the Church begins to impact on their rotten concerns.’ [6]

Full-page advertisements were published in the principal newspapers controlled by theoligarchy from ostensibly religious groups, who called themselves ‘The Salvadoran Catholic Society’ or ‘Catholic Women’s Union’. They contained vile attacks on Romero and the Jesuits. A far-right campaign leaflet even suggested that the pope should perform an exorcism on Romero. On 21 June 1977, the death-squad ‘Union of White Warriors’ demanded that the Jesuits leave the country within 30 days – otherwise they and all their institutions would become ‘military targets’. Romero uncompromisingly took the side of the Jesuits. They stayed in the country and (for the time being) nothing happened after the 21 July deadline.

Although previously he had taken his decisions on his own, now Romero took advice from the most varied people and groups. Dialogue became his hallmark. He surrounded himself with three advisory bodies: one for pastoral matters, another for legal affairs, and a third for political questions. In this way he let go of any top-down, authoritarian model of Church, where the bishop commands and everyone else obeys. In a sermon, he said of the participative model that he was now exemplifying: ‘we cannot speak and impose, but we have to invite to a dialogue of reflection in the light of the Gospel’ (III, 222).[7] He gave up his hierarchical authority and thereby won a towering moral authority.

Even his pastoral letters were no longer written just by him, instead they were the product of a process of dialogue and consultation. When he was preparing his third pastoral letter on the Church and the grassroots organisations, he sent out questionnaires to the local communities, so that he could bring into it the experiences and opinions of the people. Once he even sent a survey round the clergy and the religious orders so that he could hear any criticism they had of his conduct of his office and of the pastoral direction of the archdiocese. When he was on retreat with priests, he explicitly asked them to let him know his failures and weaknesses.

From charitable work to structural reform

With this transformation in Romero, there also came the insight that the problems of El Salvador could never be solved by charitable work alone; rather, questions needed to be asked about the causes of poverty and injustice. He made this clear in his sermon on 16 December 1979: ‘A genuine Christian conversion today has to unmask the social mechanisms that marginalise workers and farmers. Why is there only income for the campesinos, poor as they are, during the coffee harvest, the cotton, the sugar-cane harvest? Why does this society require farmers who have no work, badly paid workers, people without a just wage?’ (VI, 63). He saw it as a duty above all for Christians to unmask these interconnections, so that they would not become complicit in the dominant system that was producing ever more poor, marginalised and indigent people.

Thus Romero made the step from a charitable to a structural approach in his war on poverty. It was the step that Archbishop Hélder Câmara once pithily described thus: ‘When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why the poor have no food, they call me a communist.’ Following his own logic, Romero moved away from any paternalistic concept of aid, in the way that he himself had once practised it: ‘We do not serve the poor with paternalism. Aid from those above to those below. That’s not what God wants, rather a relationship between brother and brother.’ (V, 272).

Anyone who asked about the reasons for injustice called the system in power into question. So those who profited from that system felt their interests were being threatened. ‘Those’ included the USA. In the wider geopolitical context of the Cold War, the government of the USA was supporting military regimes in Latin America and attempting to prevent the emergence of left-leaning governments. A few weeks before his murder, Romero wrote a letter to the then president of the USA, Jimmy Carter, and asked him to halt the supply of weapons to the Salvadoran army, because they were being used to massacre the civilian population.

Romero was accused of betraying his proper work as a pastor and of involving himself in politics. But he had learnt to see ‘eternal salvation’ and ‘earthly justice’ in a new light, as bound to one another. He explained this point in his second pastoral letter:

The Church is persecuted because she wants to be the real Church of Jesus Christ. As long as the Church proclaims a redemption in the beyond, without plunging into the harsh realities of this world, she is respected and praised and showered with favours. But when she is true to her mission and points out the sin that casts so many into misery, when she proclaims the hope for a more just, a more human world, then she is persecuted and abused, and called ‘subversive’ and ‘communist’. (VII, 72)

A bishop in the spirit of the Second Vatican Council

In the course of his lifetime Oscar Romero lived out the fundamental transformation in the understanding of the Church that came with the Second Vatican Council, from a societas perfecta, closed and hierarchical, to ‘the people of God’ and ‘Church of the poor’. One of his earliest printed documents is a sermon for the funeral of his friend, Auxiliary Bishop Rafael Valladares, on 2 September 1961. It shows an understanding of Church that is still triumphalist and purely supernatural. But in the years that followed he made his own the council’s new understanding of the Church as the people of God, on pilgrimage through history, in service of the world and of humanity. The Church of the council understood itself as the sacrament of salvation and unity among people, which made the historical and social dimension integral. Accordingly, Romero set himself against ‘a merely spiritualised Church, a Church of the sacraments, of prayer, but without any social engagement, without any engagement with history.’ (I, 101)

For Romero, one of the essential characteristics of the Church is its concern for the poor. ‘Incarnation and repentance, for us that means drawing closer to the world of the poor. We have not brought about the transformations in the Church, pastoral care and education, in religious and priestly life and in the lay movements, by giving ourselves over to introspection. We achieve them, when we turn to the world of the poor’ (VII, 193). This is closely bound up with the Church’s prophetic task to proclaim the truth and challenge injustice. By performing it, she exposes herself to contradiction and persecution. Yet persecution for the sake of justice is a sign for Romero that the Church is accomplishing her mission. Thus he added to the classical list of distinguishing features of the Church that of persecution, and applied to the Church the Gospel claim that that the ultimate consequence of following Christ is to give one´s life.

For Romero, the Church is always a Church of sinners, and he acknowledges himself to be the foremost of them. In his second pastoral letter he spoke, too, about ‘sinfulness in the Church itself’, which also needed repentance. The cardinal sin of the Church consisted for him in the times when its teaching was contradicted by its actions. It is a fundamental temptation for the Church to come to an understanding with the powerful. When necessary, she has to be ready to lose all her privileges.

It is no honour for the Church to be on good terms with the powerful. The honour of the Church consists in this, that the poor feel at home in her, that she fulfils her mission on earth, that she challenges everyone, the rich as well, to repent and work out their salvation, but starting from the world of the poor, for they, they alone are the ones who are blessed. (VI, 283)

The Church falls short of her commission when she tries to keep herself out of history, when she takes the side of the mighty, when she does not seriously and faithfully accept the Easter message of death and resurrection as intended for herself. The Church fulfils her mission by building up the Kingdom of God, and as the first Beatitude proclaims, that Kingdom belongs to the poor. The motto Romero chose at his episcopal ordination was Sentire Cum Ecclesia – literally, ‘“feeling”’ with the Church’. And that meant more and more for Romero, as time went on, feeling as the poor felt. It was in the poor that he encountered Christ present, living on in history, as he put it so powerfully in his second pastoral letter on ‘the Church as the body of Christ in history’. It was in them that he encountered the suffering Christ, which led him to use the language of ‘the crucified people’.[8]

Romero and Liberation Theology

One of the major reasons that the beatification and canonisation of Romero has taken so long is that he was identified with Liberation Theology, which emerged 50 years ago in Latin America and was highly contested within and beyond the Church, but at whose centre lies the option for the poor and the connection of faith and justice. [9]

Before his conversion, Romero opposed Liberation Theology. It seemed to him dangerous for Church and theology to get involved in social and political questions. During his own theological studies at the Pontifical Gregorian University he had studied neo-scholastic theology, which at that time was obligatory. In this system, sharp boundaries were drawn between ‘grace’ and ‘nature’ and as a consequence of that, between God and humanity, Church and world, faith and history. Together with this went a particular understanding of spirituality, with just as clear a demarcation between the world and God, body and soul, action and contemplation. Life in this world was understood as just as a way-station on the journey towards eternal life. That was why the Church had to concern itself with the salvation of souls. Her primary goal had to be to ensure that as many people get to heaven as possible, and the most important means to this were the sacraments.

Within this ecclesial, theological and spiritual framework, it was only logical that Romero would for a long time put the sacraments at the centre of his priestly activities, and not concern himself unduly with secular affairs. Accordingly, until 1977, Romero had a negative view of Liberation Theology. He described it as a ‘theological fashion’, and dangerous for Christian faith. In a confidential memorandum that he drafted in 1975 while a consultor on the papal commission for Latin America, he took critical issue with the theology of Ignacio Ellacuría SJ and Jon Sobrino SJ. The Vatican authorities reacted swiftly and for the first time Ellacuría and Sobrino were forced to defend their theological position. But after his transformation, his attitude to Liberation Theology altered as well and he made Ellacuría and Sobrino his closest advisers. A diary entry gives an indication of the change in Romero and of his later thinking, where he describes with satisfaction how, while in Louvain at the beginning of 1980, he managed to lay to rest the reservations of a Belgian theologian concerning Liberation Theology.

Another accusation was that Romero was a puppet of the Jesuits. Ignacio Ellacuría SJ, Rector of the Central American University, who was himself murdered in 1989, gave a clear rebuttal of this in 1985, in a speech at the award of a posthumous honorary doctorate to Romero.

People claimed, with malicious intent, that Archbishop Romero was manipulated by our university. It is fitting at this moment to say publicly and solemnly, that that is not true. Certainly, Archbishop Romero on many occasions asked us to work with him. For us this meant – and still means – a great honour: both that he asked for our help, and the object of his concern… but in all this co-operation there was never any doubt about who was in charge and who was the assistant, about who was the shepherd, setting the guidelines, and who carried them out, about who was the prophet, who opened up the mystery, and who was the disciple, who gave the impulse and who received it, who was the voice, and who was the echo.[10]

A political and ecumenical saint

The Salvadoran bishops had asked Pope Francis to canonise Romero in El Salvador. But the fact that he is being canonised in Rome underlines his significance for the Church worldwide. As a Latin American saint, he highlights that transition from a European-centred Church to a genuinely global Church, whose accomplishment can be seen in the election of Pope Francis. For the latter, Oscar Romero is a model for imitation. In the witness of his life, we can see what the pope means by his vision of ‘a poor Church for the poor’. Romero is an example of a bishop who has ‘the smell of the sheep’ and who walks alongside his flock.

In his efforts for justice and human rights, Romero was political. Pope Francis, too, wants the Church to take on a political role, through a commitment to peace, justice and the care of creation. In the same spirit he himself has played an active role in setting up a dialogue between the governments of the USA and Cuba, with the goal of lifting the decades-long US sanctions against the Caribbean island. With his encyclical Laudato si’, he had a significant impact at the world summit on climate change in Paris in December 2015. Again and again, Pope Francis has involved himself in the European political debate on migration. Standing before the European Parliament in Strasbourg and to the applause of the MEPs, he warned that we could not allow the Mediterranean Sea to become one giant graveyard.

One other important aspect is that Romero has an ecumenical significance. He is an ecumenical martyr. Just how important he has long been in the eyes of other Christian Churches is made clear visually above the Great West Door in Westminster Abbey, where, since 1998 his statue has stood with nine other martyrs of the 20th century including Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Martin Luther King. And Romero is a saint for the whole world, far beyond El Salvador. You could say that he is just the saint for the global context in which we find ourselves today. It is not only in Latin America, but in North America, Europe, Africa and Asia, that groups have formed who live out the option for the poor in his spirit. The United Nations has declared his anniversary an ‘international day for the right to the truth concerning gross human rights violations and for the dignity of the victims’. On 16 January 2015, the then General Secretary of the UN, Ban Ki-Moon, visited his tomb in the crypt of the Cathedral in San Salvador. Romero inspires many people beyond the confines of the Church who are committed to a more just and a more human world.

Romero’s legacy

Judged by human standards, Oscar Romero is a failure. After his murder, El Salvador was plunged into a twelve-year civil war that claimed 75,000 victims. Even today the country is suffering under a wave of violence, because the real cause of the civil war has not been dealt with: extreme social injustice. But in spite of that, Romero still radiates hope today: hope that both at the personal and structural level, it is possible to change; that humanity is more powerful than violence; that the gift of one’s life is the greatest testimony of love. If you ask poor people in El Salvador what he meant for them, the answer comes: ‘he told the truth and defended us, and that’s why they killed him.’

‘Raising someone to the altar’ can bring the risk of making them remote and idealised – Jesus himself pointed out the ambiguities surrounding the tombs of the prophets. We can only fittingly venerate Saint Oscar Romero when we walk his way. When we speak the truth about this world, a world of victims; when we ask the question about the reasons for poverty and injustice; when we call the idols of our age by name and resist them; when we are prepared for danger and conflict; when we are borne by the conviction that self-gift is more powerful than egoism and that love is stronger than death.

The clearest indicator of the humanity of a society is how it deals with its weakest members. Pope Paul VI, in his address to the United Nations in New York in 1965, described the Church as ‘an expert in humanity’. Therein lies the task for the Church in today’s world, the claim by which she must also allow herself to be judged, in nations of the south as in the nations of the north. Everywhere, she has to take the part of the weakest. In Europe that means quite specifically the refugees, the jobless, the homeless, the victims of sexual violence and exploitation, the unborn children and those who are born and neglected, the abandoned elderly. To venerate Romero means to walk his way: to call injustice by its true name and to promote justice. ‘Raising Romero to the altar’ has to go with raising the poor and the marginalised of this world to ‘a life worthy of a human being’. Then, in his words, ‘The glory of God is the poor, fully alive’.

Martin Maier SJ is the Secretary for European Affairs at the Jesuit European Social Centre in Brussels.

This article was translated from the original German by John Moffatt SJ, and is also published in German by Stimmen der Zeit, in French in Études and in Swedish in Signum.

[1] Klaus Hagedorn (ed.), Oscar Romero: Eingebunden: Zwischen Tod und Leben (Oldenburg, 2006), p.33 ff.

[2] Oscar Arnulfo Romero, In meiner Bedrängnis: Tagebuch eines Märtyrerbischofs 1978 – 1980, (Freiburg, 1993), p. 40 ff. This is an abridged version from the Spanish original. [English version: Irene Hodgson (trans.), Oscar Romero: A Shepherd’s Diary (St. Anthony Messenger Press: Cincinnati, 1993) available online at http://www.romerotrust.org.uk/documents/books/Ashepherdsdiary.pdf]

[3] Ibid., p.119.

[4] For a more extensive treatment. see Martin Maier, Oscar Romero: Prophet einer Kirche der Armen (Freiburg, 2015).

[5] Arturo Rivera y Damas, ‘“Presentación” in Jesús Delgado’, Oscar Romero: Biografía (San Salvador, 1990), p.3.

[6] Romero, Tagebuch, p. 185.

[7] Citations for Romero come from the seven-volume critical edition, Homilias: Cartas Pastorales: Discursos y otros Escritos (San Salvador, 2015 – 2017). Roman numerals denote the volume, Arabic numerals the page numbers.

[8] Cf. Martin Maier, ‘On the theology of crucified peoples’ in Klaus Hagedorn (ed.), Biotope der Ermutigung: 25, Jahre Hochschulpastoral in Oldenburg, Oldenburg, 2008), pp. 371 – 388.

[9] Cf. Martin Maier, ‘Monseñor Romero y la teología de la liberación’ in Revista Latinoamericana de Teología 99 (2016), 201 – 214. Also on: www.romerotrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/Romero%20and%20Liberation%20Theology%20Maier.pdf

[10] Ignacio Ellacuría, Escritos Teológicos III (San Salvador, 2002), p. 103 ff.