Yesterday, 24 March, was the thirtieth anniversary of the assassination of Oscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador. Bishop Maurice Taylor, who knows the country well, preached this homily at a memorial Mass at St Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh, to mark the occasion. Who was Oscar Romero? How did he make such an impact on the Church in El Salvador? And why was he killed?

When Central America gained independence from Spain nearly 200 years ago, it soon split into five separate and different republics: Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and El Salvador.

Of the five, El Salvador is the smallest in area. It is also the only one whose name is a Christian name – a name that could not be more Christian: El Salvador, The Saviour – yet its people are probably the most argumentative and combative in all of Central America. Nonetheless, as if the name of the country were insufficient, its capital city is San Salvador (Holy Saviour) and many of the towns have saints’ names. For example, I spent some time as the temporary priest in charge in the town of Dulce Nobre de María (literally, Sweet Name of Mary).

El Salvador, like the other independent republics of Central America, inherited from Spain a legacy of autocracy. Power and wealth lay with a minority, even an oligarchy, whose members, generation after generation, succeeded in retaining their wealth and power. The great majority of the people were poor, ill-educated, kept marginalised and without prospects. Proper reform was not on the agenda – neither political nor judicial reform, nor land reform. The status quo had to be maintained and it was maintained principally because the few had most of the land and the best of the land, the most productive land. And why should they give up such a comfortable and privileged lifestyle by allowing a more equitable sharing of nature’s riches and life’s opportunities?

Of course, this unjust state of affairs began to be challenged. There were some attempts at armed rising earlier last century, but they were suppressed ruthlessly and without great difficulty. In the 1970s, unrest began to grow in a serious and widespread way and the army was used for what was called counter-insurgency. In addition to the uniformed forces of the republic, officered by men from the privileged classes, there also began to exist death squads, employed by powerful and brutal elements. The result was that the poor, whether the urban poor or the peasants, were living in fear as well as in poverty and in the midst of conflict.

Gradually, those brave enough actively to fight the structural injustice coalesced into an armed organisation called the Farabundo Martí Front for National Liberation and usually known as the FMLN (Farabundo Martí had led an unsuccessful revolt earlier in the century). Thus, around the year 1980, civil war began in El Salvador, a war that, from the army’s point of view, was waged on a ‘search and destroy’ basis while the FMLN fought a guerilla type of campaign.

Since Central America is in what is called the United States’ sphere of influence, the US government was, in various ways, active in El Salvador. It had much financial and commercial involvement in the country and that, along with an obsession about communism in the hemisphere, ensured that the United States provided financial, diplomatic and even military support to the regime and its policies of repression.

During this time what was the Catholic Church in El Salvador doing? Rather, let me phrase that differently: What was the Church leadership doing? On the whole, the bishops supported the status quo, either by giving active encouragement or by their silence and non-intervention. There are several possible reasons for this. Some bishops came from the wealthy sector of the population; some feared the opposition to right-wing governments was Marxist-inspired; others perhaps on the specious grounds that the Church should not interfere in politics (even when those politics are blatantly unjust).

Despite the very encouraging teachings coming from meetings of Latin American bishops in Medellín and Puebla, many bishops in that part of the world have either been hostile to those actively engaged in trying to change the unjust structures so widespread, or, at least, have shown little or no enthusiasm for such endeavours. And, since bishops are appointed by Rome and only after careful investigation into their backgrounds, opinions and suitability, one sometimes wonders. Similarly and personally, I have to say that the Holy See’s attitude to liberation theology and to Small Christian Communities has often been suspicious and negative; but to say more on that would take us down another path.

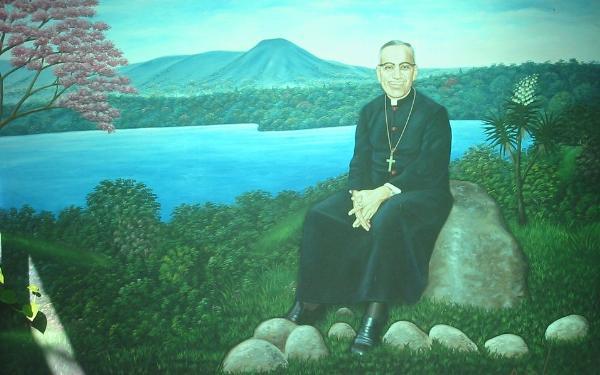

When the Archdiocese of San Salvador needed a new archbishop in 1977, there was satisfaction in government circles that the Vatican’s choice fell on the relatively little-known Oscar Arnulfo Romero. He was bishop of Santiago de Maria, a small rural diocese in the east of El Salvador. The general expectation was that he would have little to say about the injustice and violence rampant in the country. Perhaps Oscar Romero himself, when nominated to the capital, had little thought of getting deeply involved. But it is one thing to be bishop of a small diocese away from the centre of things and another to be archbishop in the capital city and very much in the public eye.

His tenure of office in San Salvador was very short – only three years, but what a heroic and inspirational leader he turned out to be. He probably knew that, as archbishop of the nation’s capital and the seat of the government, he could not ignore the prevalent and intolerable situation. God gave him the wisdom and the courage that he needed and he did not fail in his duty.

The new archbishop did not have long to wait before having the opportunity to declare where he stood. The Jesuits had been particularly courageous and outspoken on behalf of the victims of the oppression and in their criticism of injustice. Soon after Romero became archbishop, Father Rutilio Grande, a Jesuit and the parish priest of a village in the archdiocese, was assassinated by a death squad. The archbishop was swift, unequivocal and public in his condemnation of the crime.

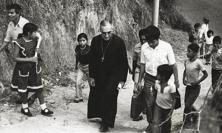

Thereafter, his weekly homilies at Mass in his cathedral were broadcast nationwide by Radio Católica. As the violence increased, as the army became more and more ruthless against the peasants, as death squads operated with impunity, the archbishop’s homilies became increasingly critical and proved a much-needed solace for the oppressed and fearful people. He condemned the violence and declared that it was the consequence of the injustice in Salvadoran society. He called on the authorities in God’s name to halt their policy of cruel and unmerciful repression. Each Sunday, as well as the archbishop’s homily, a list of the names of the victims killed in the previous week was broadcast.

The government objected to the archbishop, denied his accusations and called on him to desist. Not for the first time nor for the last, a veritable reign of terror gripped the country. Archbishop Romero became so distressed about the situation that he even appealed to the ordinary ranks in the army not to obey orders to kill their innocent fellow-citizens. For the archbishop’s enemies, that was the last straw. He had to be silenced.

He spent Monday 24 March 1980 with a group of his priests, relaxing at the beach, an hour’s drive south of San Salvador. In the afternoon he returned to the city and to his own house, a little cottage in the grounds of a hospital. He then walked the short distance from his cottage to the hospital chapel. He had arranged to celebrate an evening Mass there. Having completed the Liturgy of the Word, he had just taken the bread in his hands to commence the Liturgy of the Eucharist when a shot was fired and he fell to the floor behind the altar, dying or already dead. A hired marksman had been driven into the hospital grounds and, from the vehicle and through the open door of the church, had fired the fatal shot.

Oscar Romero’s death shocked millions of people throughout the world, nowhere more so than in El Salvador. No doubt his assassination satisfied many powerful people in the military and the government. No one has ever been brought to trial for the crime. It is believed that the hired assassin and the car driver were themselves soon murdered to ensure their silence.

The archbishop’s funeral in San Salvador cathedral was attended by huge crowds, including bishops and others from abroad, which served to highlight the absence of all but one bishop from El Salvador itself. The absence of the local bishops has sometimes been attributed to disagreement with the archbishop’s very public views or to apathy and indifference. It is neither our right nor our duty to judge. But unfortunately also, the lack, so far, of official Church recognition of Romero’s murder as truly a martyrdom causes sadness and dismay to many. The lack of progress towards beatification and canonisation is hard to fathom, but perhaps it is unimportant. Millions of ordinary people who, after all, are the Church and provide a sensus fidelium do not doubt that he is a saint.

Oscar Romero had declared that, even if he were killed, he would live on in the hearts of his people. This he assuredly does – not only in the hearts of his fellow Salvadorans but also in the hearts of countless people throughout the world who venerate him. They – we – believe he is a martyr-saint and pray that we may be inspired by the faith and courage of a heroic disciple of Jesus Christ, Oscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador.

Rt Rev Maurice Taylor is Bishop Emeritus of Galloway and Vice-President of Progressio. He was Bishop of Galloway from 1981 to 2004.