A conversation with the author of a powerful novel about the six Jesuit priests who were killed in El Salvador on 16 November 1989 prompted Mark Dowd to reflect deeply on the final few hours of the martyrs’ lives. How might their experience have compared to others in which mortal danger was only days, minutes or even seconds away? Is there a way in which faith and prayer can shape our response in so-called ‘fight or flight’ situations?

These last few days I’ve been obsessed with the human autonomic nervous system. One particular element has captured my attention: the so-called ‘fight or flight’ response. When faced with a violent threat to life, the body goes into overdrive. The tiny amygdala in the brain sends out signals via the hormone, epinephrine, and within seconds, via a chain reaction of neurotransmitter responses, the heart is pumping blood, lungs are taking in more oxygen, pupils are dilated to increase awareness of danger and sweat covers the skin. It will evaporate within seconds, keeping the human body cool under pressure. All of these physiological responses will assist you whether you opt for either ‘fight’ or ‘flight’. But that decision to stay or bolt can never be a purely physical one: it is ultimately one rooted in a deeper moral identity. As the celebrated rock song from the Clash asks, ‘Should I stay or should I go?’

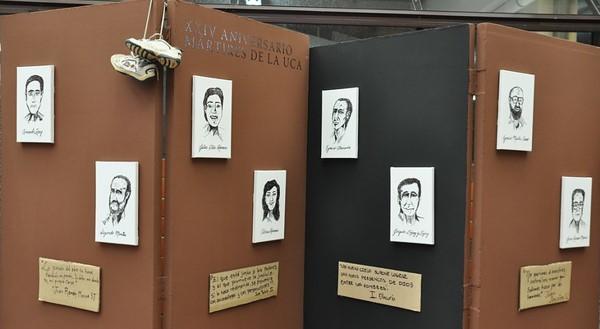

What provoked such musings was a session I chaired last week at the London Review Bookshop with the Salvadoran author, Jorge Galán. He was discussing his new book, Noviembre, about the events surrounding the murder of the six Jesuit priests and their housekeeper and her daughter on 16 November 1989. It was the evil work of a ruthless, army-sponsored death squad during the civil war which raged in the tiny Central American country between 1980 and 1992. In his gripping account, Galán refers to a visit by soldiers to the Jesuits’ house at 6.30pm in the evening, just hours before the brutal massacre. He calls it El Cateo, ‘the search’. In effect, it was a reconnaissance mission, to check out who was around and the configuration of the rooms in the building. Once the soldiers had come and gone, imagine the atmosphere in that house. The principal target for the Atlacatl Battalion was Father Ignacio Ellacuría SJ, who was said to be close to brokering a peace deal between the guerrilla insurgency and the military government. But his Jesuit brothers must have all known they were in mortal danger. They held their ground and paid the price only hours later, in the dark of the night, with their lives. And because the assassins were under orders to leave no witnesses, so too did Elba and Celina Ramos. The international revulsion to the murders was so great that many, in hindsight, saw it as a turning point on the road to an eventual peace.

What values, what deep-rooted loyalties in the human soul can combat the ‘fight or flight’ syndrome and opt for a third way: submission to a fate that almost certainly leads to the surrender of one´s own life?

My conversation with Jorge Galán prompted me to revisit the 2010 film, Of Gods and Men, which centred on the French Cistercian community at their monastery at Tibhirine in Algeria in 1996, when the gentle monks came face-to-face with the threat of Islamist militias during the civil war. They too faced a Gethsemane moment, and the film chronicles the tensions within the brethren about a decision to stay or leave, which reaches a dramatic climax with a show of hands. A decision was made to honour their decades of service administering medicines and education to the local town community. Both the Jesuits of El Salvador and the Trappists of Tibhirine were fortified in their resolve by having taken a collective decision. Any subsequent wavering by an individual motivated by an understandable, instinctive sense of self-preservation might have been tempered by the bonds forged of acting together. All for one and one for all, if you will.

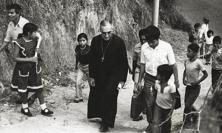

Such ties and loyalties are not, alas, available to those who act in isolation. When Saint Oscar Romero preached his unforgettable sermon on 23 March 1980 in San Salvador’s packed Metropolitan Cathedral, in which he urged the death squads to cease the repression and desist from murdering their fellow campesinos, he must have known his days were numbered. We will never know how much Romero saw of his sniper assassin the following day as he celebrated Mass in the chapel at the Hospital of Divine Providence. The temptation is to assume that saints are superhuman and immune from the fears of mortals. But all the evidence points to the contrary. Jan Graffius, curator of Stonyhurst College, who was entrusted with the task of preserving Romero’s possessions, wrote in these pages six years ago about a shock discovery when she was in the capital of El Salvador and carrying out her work:

…it was during a minute examination for mould on the black woollen trousers that I had my most moving insight. They were covered with a white, speckled deposit, formed into circular pools, which at first sight appeared to be some kind of mildew, although it did not resemble anything I had come across before. Under magnification it became clear that these were salt crystals – the residue of a sudden and profuse sweat. According to eyewitnesses at his last Mass, Romero suddenly flinched, having seen the gunman at the door of the church.

In this sudden moment staring at death, quite literally down the barrel of a gun, no-one was in the frame alongside Monseñor Romero. He was totally exposed and defenceless. Yet he also had Christ alongside him. Surely that was his firm conviction when one considers how he responded to those around him who gave warnings that his ever more trenchant criticisms of the military government were going to lead to his premature death? ‘If they kill me,’ he said, ‘I will rise again in the Salvadoran people.’ When you have such faith, anything is possible, even if you are doing everything possible to combat the urge to fight or to flee. Such faith, nevertheless, does not inhibit the spontaneous workings of the automatic nervous system.

In the aftermath of Gethsemane, of course, Jesus neither fought nor fled. As a keen and inquisitive primary school child at St Mark’s in Salford, I recall the perplexed looks on the teacher’s face when my curiosity got the better of me. If the apostles had all fallen asleep and Jesus was left totally alone to ponder his fate in the garden, who on earth was around writing down all his words?

My Father, if it is not possible for this cup to be taken away unless I drink it, may your will be done. (Matthew 26:42)

I never did get a satisfactory answer to my question as a ten-year-old, but fifty years on different questions remain. For Jesus, in nature both truly divine and truly human, what was the essence of that existential hour of torment? Was there some flash-frame of fast-forwarding horror to physical glimpses of what was to occur in under 24 hours? Does advance premonition of fate produce the sweat that results in drops of blood? Or was there an even more profound dread and sense of torment? Only three years after I posed those primary school questions I became enamoured of the music of Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar. The song that made its greatest impression on me was the Gethsemane solo, ‘I Only Want to Say’, sung on my MCA label recording by Deep Purple’s Ian Gillan.

Why should I die? Oh why should I die? Can you show me now that I would not be killed in vain? Show me just a little of your omnipresent brain Show me there's a reason for your wanting me to die You're far too keen on where and how, but not so hot on why.

The precise detail of what went through the mind of Jesus in his passion is, of course, pure conjecture. But this suggested notion of wasted mission, of it all being ultimately pointless I find on a par with the cry from the cross, ‘My God, My God, why have You forsaken me?’ It is a cry of despair and abandonment.

The Cistercians had each other as they were led away to their fate by their captors. So too, in their savage moment of annihilation, the Jesuit martyrs were together in that sense of shared destiny; and, of course, they had an inspirational loyalty to Romero who had gone before them nine years previously. Saint Oscar Romero no doubt cleaved to the inspiration of Christ’s kenosis, his self-emptying to the will of the Father.

But in all this reflection, I sense the utter aloneness and bleakness of an unsupported Jesus in that garden. It has taken sixty years of my life for this finally to feel real, to feel its call to stare into a nihilistic void. The very grounds of his deepest nature summon him, ultimately, to choose a course which transforms the world.

‘Love endures’, says Father Christian de Chergé, head of the Cistercian community as they vote to stay and face their aggressors. ‘Love endures.’

Mark Dowd is a freelance writer and broadcaster. He is the author of Queer & Catholic: A life of contradiction (Darton, Longman & Todd, 2017).

Jorge Galán’s novel, Noviembre, won the Premio Real Academia Española in 2016, and is now available in an English translation by Jason Wilson as November, published by Little, Brown Book Group in 2019.

Listen to a reflection on the Jesuit martyrs of El Salvador that was produced by Pray as you go for the martyrs' 25th anniversary: soundcloud.com/pray-as-you-go/reflection-on-the-jesuit-martyrs-of-el-salvador