‘Under magnification [of Oscar Romero’s black woollen trousers] it became clear that [there] were salt crystals – the residue of a sudden and profuse sweat...Whether or not he had time consciously to realise that death was imminent, his body reacted and sweated heavily. One cannot but think of the Garden of Gethsemane.’ For the anniversary of Oscar Romero’s death on 24 March, Jan Graffius writes movingly about the preservation of his possessions and those of the El Salvador Jesuit martyrs.

It is very pretty to like a piety only of songs and prayers, only of spiritual meditation, only of contemplation. The hour for such things will come in heaven, where there won’t be any injustices, where sin will not be a reality that Christians will have to dethrone. Now, Christ said to the contemplative apostles who wanted to stay forever on Mount Tabor, ‘Let’s go down, we have work to do.’ (Archbishop Oscar Romero, 19 November 1978)

I have been privileged over the last five years to work towards the preservation of the possessions of Archbishop Oscar Romero, murdered on 24 March 1980, and the Jesuits of the University of Central America in El Salvador, killed on 16 November 1989. In the course of this work, on behalf of the Romero Trust and aided by Jesuit Missions, I have encountered people and objects which have brought me to a deeper understanding of the tragedy of the Civil War in El Salvador. They have shown that truth can be found in objects as well as in words.

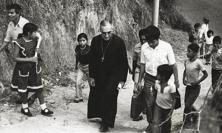

Monseñor Oscar Romero became the spokesman for the oppressed poor of El Salvador. During his brief time as Archbishop of San Salvador, he called unceasingly and authoritatively for an end to the violent repression taking place in his country. The quotation above is typical of the man, practical and determined. He was murdered saying Mass on 24 March 1980 in the chapel of the hospice where he lived, on the orders of a government who could find no other way of silencing him. Nine years later, a group of six Jesuit theologians at the University of Central America (UCA) in El Salvador were murdered by the army death squads. Their offence had been to work for reconciliation between the government and the rebels who opposed them. Romero and the Jesuits were repeatedly traduced as Marxists and traitors by the official voices of the press and the government. Their words live on to belie that smear, and the few small possessions they left behind have their own story to tell.

Sister Maria Julia runs the Carmelite Hospitalito di Divino Providencia for the terminally ill, and is the custodian of Romero’s little house and its contents. Jon Sobrino, the renowned Jesuit theologian and co-worker of Monseñor Romero, was also a colleague of those murdered in 1989 and is responsible for the ‘Sala de los Martires’ shrine and display at the UCA. Along with many others who work with them, Fr Sobrino and Sister Maria Julia have saved and made accessible a powerful group of objects, ranging from simple socks, spectacles, manuscripts and woolly hats, to eloquent, blood-soaked clothing, cut with machetes, pierced with bullet holes, engrained with dirt and worse. Visited by thousands of pilgrims every year, they have a powerful effect on all who see them.

Everything in a curator’s care is treated equally, be it a Leonardo drawing or a 1930s tin of beans. But some objects seem to have a deeper and more profound importance. Those who first saved the Salvadoran objects understood that they are truthful witnesses to courageous lives lived in the light of the gospels, and to violent deaths in the service of Christ and His poor. They have a vital role in a country where official distortion and lies were commonplace, and in a world which often struggles to understand integrity, courage and holiness. Curators rarely get to deal with objects that speak as powerfully as these.

In many ways, museum professionals spend their lives trying to delay inevitable decay, to extend the life of objects which demonstrate a perverse and ungrateful determination to return to the dust from which they came. In Spanish, as Jon Sobrino once pointed out to me, the word curador means both ‘healer’ and ‘curator’, and it is easy to see the role in terms of a medic in an intensive care unit striving to keep ailing artefacts going just a little bit longer (although the job is just as much that of cleaner, story-teller, Dickensian scribe, embalmer and amanuensis).

Stonyhurst College, where I work, cares for a unique collection of objects which illuminate the history of English Catholicism from the 7th century onwards, and the work of the Society of Jesus as missionaries, priests, teachers and martyrs in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was working with this important collection, partly the property of Stonyhurst and partly that of the British Province entrusted into the College’s care, which led to my involvement in El Salvador. As this project has progressed, I have been repeatedly struck by the parallels between the 20th century Salvadoran martyrs and the English martyrs of four hundred years earlier. Both were in conflict with established authority, both denounced entrenched injustice, both were declared traitors, both struggled to work as pastors under constant fear of death, both were executed on official orders, and the relics of both were, and are, treasured and preserved, giving hope to those who follow in their footsteps and those who suffer from similar injustice and repression.

Relics are a touch unfashionable these days. They have a whiff of traditionalism, and are, perhaps, associated with a love of elaborate liturgy, the use of ‘correct’ form, and a slightly embarrassing piety which has passed into history. They are definitely not part of the British cultural mindset. But my experience demonstrates their deep and enduring power to speak of bravery, faith and commitment, of injustice resisted and the harsh price exacted in return.

Community memory is preserved in material artefacts, and we have an entrenched need to keep things which belong to those we have loved; ask any mother about baby shoes, locks of hair, handmade birthday cards and the like. The early Church collected what shattered fragments it could from those first martyrs, and built its first altars over the blood-soaked earth consecrated by the deaths of Lucy, Agnes, Cecilia and so many others. And my work with pupils at Stonyhurst has shown me that nothing emphasises the reality of sacrifice and devotion quite like a sliver of bone or the skin or hair of a human being who has died in Christ, collected clandestinely by followers who risked their own freedom to show honour to those who have given their lives for their beliefs.

The objects I worked with were divided between two sites in San Salvador: the tiny house where Romero lived as archbishop, within the precincts of the Hospitalito, and the Sala de los Martires in the UCA. I recorded, photographed, catalogued, carried out basic conservation, made new supports for fragile vestments and artefacts and gave advice on display methods, light levels and environmental control.

Romero’s house consists of three small rooms and a bathroom. It contains books, a desk with his typewriter and tape recorder, a single bed, a few chairs, a wardrobe, and his much-loved white cotton hammock slung across the smallest back room. Most of his possessions are now, necessarily, behind glass to prevent damage by the many pilgrims who visit daily. Outside, in the drive, sits his beige Toyota Corolla, once a familiar sight in the city. Visitors are struck by the simplicity of his accommodation and his sparse possessions. Some have the power to move, such as his personal diary with bookings and appointments scribbled in for the weeks following his murder, or his instantly recognisable spectacles. His clothes, many handmade, are immaculately pressed and hung in a glass-fronted wardrobe. Romero was aware that as an archbishop he had a duty to be appropriately dressed, but he achieved this without excess or lavish expenditure (although there is a particularly beautiful charcoal grey suit with an apricot silk lining, bought in Rome, which made me smile, so incongruous it seemed amongst the black soutanes and grey shirts). While recording his clothing I was surprised to find that there were only three pairs of socks, and was told by one of the sisters that he would wear one pair, have one in the laundry and one in the drawer – the bare minimum.

Most visitors come to see the Martyr Vestments, as they are known. In a glass-fronted case in the back room hang a simple purple cotton chasuble, a white alb and cincture, a grey cotton shirt and a pair of black woollen trousers – these are the clothes he was wearing when he was murdered while saying Mass. At first glance, one’s eye is drawn to the alb, which is shockingly stained with quantities of blood. A large area of cloth around the chest is missing altogether, hacked away by doctors trying to get to the bullet wound. The chasuble seems unstained, but this is because the purple cotton makes it difficult to see the blood. What you do see though, is a tiny opening, barely a centimetre in length and more of a cut than a hole, directly over the heart. A single, high velocity bullet entered almost without trace, but once in his body it expanded causing massive, irreversible organ damage, guaranteeing death. This tiny incision speaks of a professional gunman, cool enough to walk into a crowded church and aim his rifle at a priest saying Mass, needing only one shot to kill.

The environmental conditions in El Salvador are far from ideal for the preservation of organic materials. The temperature is considerably in excess of the desired 18-20°C, and the humidity levels are heart-stoppingly high. I recorded levels of over 90% regularly; the optimum is 55% and at 70% spontaneous mould growth appears. The Romero Trust installed a dehumidification and cooling system in the house, which has helped considerably, but constant vigilance is necessary as nature has a way of circumventing human ingenuity.

Mould spores attack fabric fibres, weakening the structure of the cloth until holes develop. Indeed it was during a minute examination for mould on the black woollen trousers that I had my most moving insight. They were covered with a white, speckled deposit, formed into circular pools, which at first sight appeared to be some kind of mildew, although it did not resemble anything I had come across before. Under magnification it became clear that these were salt crystals – the residue of a sudden and profuse sweat. According to eyewitnesses at his last Mass, Romero suddenly flinched, having seen the gunman at the door of the church. Whether or not he had time consciously to realise that death was imminent, his body reacted and sweated heavily. One cannot but think of the Garden of Gethsemane.

For me, such a revelation was profoundly moving, reminding us that martyrs are also truly human. Romero was very aware of the risks he ran in opposing the government; how could he not be, with death threats landing on his desk almost weekly? He persevered in his fight against injustice strengthened by his deep love for Christ. But he feared the prospect of death, as is shown by his personal record of a conversation with his private confessor about a month before his murder,

My other fear is for my life. It is not easy to accept a violent death, which is very possible in these circumstances, and the apostolic nuncio to Costa Rica warned me of imminent danger just this week. You have encouraged me, reminding me that my attitude should be to hand my life over to God regardless of the end to which that life might come; that unknown circumstances can be faced with God’s grace; that God assisted the martyrs, and that if it comes to this I shall feel God very close as I draw my last breath; but that more valiant than surrender in death is the surrender of one’s whole life – a life lived for God.

The Sala de los Martires is a powerful record of the sufferings endured by so many Salvadorans during the Civil War of the 1980s, when some 75,000 were murdered. It contains army mortar shrapnel and spent bullet cases from the infamous massacre at El Mozote in 1981, where nearly 1000 died unspeakably, more than half of them children. It contains the bullet-riddled shirt of Rutilio Grande, the first Jesuit to be murdered in El Salvador in 1978, and some of the clothing of the Maryknoll Sisters and churchwomen raped and murdered in 1980. Most compellingly, it contains the clothing worn by the six Jesuits on the night they were murdered in 1989, and a single blood-stained white shoe belonging to Celina, the 16-year-old daughter of Julia Elba, the Jesuits’ housekeeper; mother and daughter were both killed so as to leave no witnesses. The circumstances of all of their deaths at the hands of the infamous Atlacatl Battalion, who were also responsible for El Mozote, are made clear in a breathtaking, unbearably graphic collection of photographs taken on the morning that the tortured and shattered bodies were found, by Julia Elba’s husband.

Like Oscar Romero, these were men who lived simply, as their clothing bears out. Dragged from their beds in the early hours of the morning, tortured and shot, their pyjamas, dressing gowns and vests are stained with blood and body fluids, slashed with machete cuts, holed by machine gunfire, ground into the dirt. Such things are hard to deal with objectively, and many times during my work I had to turn away. I remember spending hours carefully removing dust from a pair of green rubber flip flops, avoiding disturbing the blood and dirt caked onto their soles. In need of a break I wandered over to the supermarket opposite the university gates and there, among the bags of coffee and sachets of frijoles, were exactly the same flip flops, on sale for $2, over twenty years later.

For me, the most powerful objects in the Sala are six simple glass coffee jars, seemingly containing some earth, twigs, leaves and the odd button. Each is labelled with the name of one of the Jesuits. They contain the brains and blood of the men, scraped from the earth where they fell. At Stonyhurst is a famous relic, encased in silver. It is the right eyeball of Edward Oldcorne, a gentle Jesuit missionary working in Worcestershire, martyred in 1606. A distance of some four hundred years has dulled the horror of a man condemned by the state to be dismembered while still alive, whose parboiled remains were collected by those who loved and respected him, to honour his sacrifice and inspire those who might follow his path. The glass coffee jars, now arranged into a simple cruciform display, bear witness to the fact that such things still happen today. The importance of these stark, human exhibits is underlined daily by the groups who come to learn and pray, guided by students of the university who tell hard stories with simplicity and honesty. These things matter, and must be preserved.

I have mentioned my awareness of parallels between the martyrs of El Salvador and the English saints and martyrs whose relics are cared for at Stonyhurst. Shortly after Romero’s murder, Jose Maria Valverde, Professor of Aesthetics at Barcelona University, wrote a poem comparing him with an English archbishop and martyr also murdered at the altar by order of his government,

Dark centuries ago,

It is told, a bishop died

by order of a king,

spattering the chalice with his blood

to defend the freedom of the church

from the secular might.

Well enough, surely. But

since when has it been told

that a bishop fell at the altar

not for freedom of the church,

but simply because

he took sides with the poor-

because he was the mouth of their thirst for justice

crying to heaven?

When has such a thing been told?

Perhaps not since the beginning,

when Someone died

the death of a subversive

and a slave.

And now as we look to a new pope, a Jesuit from South America, one wonders how long it will be before the Church catches up with the Salvadorans, who have been saying with pride and gratitude for years,

San Romero of the Americas, pray for us.

Jan Graffius is the Curator of Stonyhurst College.

![]() ‘Romero: the voice of those who had no voice’ by Michael Campbell-Johnston SJ

‘Romero: the voice of those who had no voice’ by Michael Campbell-Johnston SJ

![]() ‘Oscar Romero: the people's saint’ by Rt. Rev. Maurice Taylor

‘Oscar Romero: the people's saint’ by Rt. Rev. Maurice Taylor

![]() ‘The Continuing Presence of Archbishop Romero’ by Rodolfo Cardenal SJ

‘The Continuing Presence of Archbishop Romero’ by Rodolfo Cardenal SJ

![]() ‘Remembering the Jesuit Martyrs of El Salvador: Twenty Years On’ by Dean Brackley SJ

‘Remembering the Jesuit Martyrs of El Salvador: Twenty Years On’ by Dean Brackley SJ

![]() ‘Crosses and Resurrections: Good news from Central America’ by Dean Brackley SJ

‘Crosses and Resurrections: Good news from Central America’ by Dean Brackley SJ

![]() ‘The Martyrs of our Modern Church’ by Michael Campbell-Johnston SJ SJ

‘The Martyrs of our Modern Church’ by Michael Campbell-Johnston SJ SJ

![]() Jesuit Missions

Jesuit Missions

![]() The Romero Trust

The Romero Trust