A Mass of thanksgiving for the beatifications of Rutilio Grande SJ, Nelson Rutilio Lemus, Manuel Solórzano and Cosme Spessotto was held at the Sacred Heart Church in Edinburgh on 22 January 2022, the day of their beatification in San Salvador. In his homily, David Stewart SJ spoke about how Rutilio’s witness to the option for the poor was the hallmark of his life as a Jesuit, a pastor and a friend to Óscar Romero.

Rutilio the Jesuit

At the time of his death, unusually for a member of the Society of Jesus, Rutilio Grande was ministering in his home district. He, like every Jesuit, had heard the call of Christ the King in the Spiritual Exercises, the ‘long retreat’. These Spiritual Exercises test your call to mission. A vocation is tried and affirmed in the intense prayer of the Exercises; your initial orientation is purified, then confirmed, then set free from disordered attachments. It’s deepened as you place yourself, in Ignatius’s words, under the banner of the cross. You pray for inner freedom to be sent anywhere; think of St Francis Xavier, think of St John Ogilvie. Grande walked the same pathway of prayer as all other Jesuits. He suffered from poor mental and physical health, and frequent bouts of depression and self-doubt, but his passion for ministry transcended all that. While most Jesuits in El Salvador at the time were committed to university-level education, academic research and formation, and indeed Grande did serve for a time at the seminary, the Jesuits worldwide, at their meeting, or General Congregation, in 1975, discerned that the order’s mission was ‘the service of faith, of which the promotion of justice is an absolute requirement’. Grande went out into the villages, alongside the poorest.

Rutilio the pastor

Tilo, as he was affectionately known, was a pastor. He died a pastor: he was driving with his companions, Nelson Rutilio Lemus and Manuel Solórzano, to celebrate a novena Mass when the soldiers ambushed them. It was said of St Ignatius that he loved the big cities, but Grande was drawn to leave the city for a mission to the poorest and most neglected areas. He was excited and energised by what the Second Vatican Council, the Latin American bishops and the Jesuits worldwide had discerned. He knew from personal experience the tough lives of the campesinos, their hard labour in the coffee and sugarcane fields, their struggle for land and for a decent life. He learned that most of the productive land was owned by about two percent of the population. But he had also learned that the gospel speaks to such injustice, that to follow Christ did not mean passively accepting poverty and oppression as the will of God. Grande developed ways of encouraging the people to challenge their situation, ‘reading the signs of the times through the eyes of faith’. When Grande was installed as the new priest in Aguilares in 1972, he was determined to be a pastor among the oppressed, shaped by Vatican II’s rediscovery of the Church as the people of God, a community not a hierarchy, committed to a ‘preferential option for the poor’. In Luke’s Gospel we hear how Jesus launched his ministry by citing Isaiah’s words about bringing the good news to the poor, setting the downtrodden free and proclaiming the Lord’s year of favour. Father Rutilio was murdered for doing just that. But as then-archbishop, now Saint Óscar Romero preached at Rutilio’s funeral Mass on 14 March 1977, Grande became a pastor to the peasants out of ‘an inspiration of love and not revolution.’ His love for the people whom he served led to his martyrdom.

Rutilio the friend

Pope Francis has said that the ‘great miracle of Rutilio Grande was Archbishop Romero’. When the quiet, shy Romero had returned from Rome and been made a bishop, El Salvador’s fourteen leading rich families were relieved; they had a tame cleric, untainted by all this new theological and pastoral thinking. Grande and Romero had become close friends, despite their very different reception of what was flowing from Vatican II, but Bishop Romero was one of many who disapproved of how Rutilio was encouraging the seminarians out of the building and into the villages. It was only two weeks after Óscar became Archbishop of San Salvador that Tilo, Nelson and Manuel were intercepted by state security forces on their way to El Paisnal, Tilo’s birthplace, and met with a hail of bullets. Archbishop Óscar came to the spot as soon as he heard. He later said that, when he saw the bullet-riddled corpses of his friend and the two parishioners, he knew that if they had done this to Rutilio, it would be his path too. It’s not quite right to see here the moment of Óscar’s conversion to the option for the poor, because that had been growing in him for some time. But he knew that this moment was its confirmation.

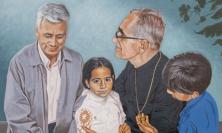

Blessed Rutilio Grande, his two lay friends and Fr Cosme Spessotto (an Italian priest who was also killed in El Salvador after denouncing the military), who was beatified with them, are an inspiration to all who do pastoral ministry in the Church: clergy, catechists, young activists, community organisers. Together they form an image, a symbol of the Church as the people of God. We’re setting out on a pathway too, the pathway of synodality, the largest ever listening exercise in the Church and, indeed, in human history. Once again, we read the signs of the times with the eyes of faith. May the prayers of Blessed Manuel, Nelson, Rutilio and Cosme, and of St Óscar, support us as we try to be the people that God wants us to be.

This article is adapted from a homily delivered on 22 January 2022 at Sacred Heart, Edinburgh, where David Stewart SJ is a member of the parish team.