In the final part of the 2009 Archbishop Romero Lecture, Dean Brackley SJ speaks of the encouragement he receives from visitors to El Salvador, and of the need for the global community to grow in support of one another to make this the ‘Century of Solidarity.’

3. International Solidarity

The crosses and resurrections of Central America draw pilgrims from far and wide. These present and future collaborators are another major source of hope.

Pilgrims. Since the UCA is on the route of many visiting groups, it is rare that a week goes by without a delegation from abroad requesting a talk –in English! I always look for a chance to tell them why we think their visit is important. It is important for the communities they visit, but also for the visitors themselves.

First-time visitors arrive apprehensive, asking themselves half-consciously: What will happen when we arrive at these poor communities where the memories of war crimes remain fresh? Will I have a massive Catholic (or Methodist, or Jewish) guilt attack? Will I have to sell my car back home to buy medicines for these people, trade in my laptop for a wheelchair? Fears like these evaporate on contact with the people, and the visitors spend the rest of their visit wondering why these people are smiling, how they keep going and why they insist on sharing what little they have with perfect strangers.

The Salvadorans smile because they feel honoured by the visit. While everything around them says, ‘You don’t count’, ‘We don’t need you’, ‘No social services for you’, ‘Better to migrate North’ – the visitors from so far away are saying something different: ‘You are important’, ‘you count for us’, ‘you matter’.

If the visitors have the courage to listen to the stories that no one else will hear – of massacres yesterday, and cruel injustice today – these poor people will break their hearts, the visitors will fall in love and then return home renewed in hope and “ruined” for life. That will be the most important thing to happen on their pilgrimage. What does in fact happen? The visitors see their reflection in the eyes of their poor hosts. With that, the ground begins to shift under their feet; the anonymous poor masses of the world suddenly take on three dimensions. They are moving from the periphery of the visitors’ world and closer to the centre. The world seems to change before the visitors’ eyes – the world they have until now half-consciously divided into important people and unimportant people. Their horizon opens.

For many younger visitors, this is a watershed experience. Their consumer society makes it difficult for them to find their way, to find themselves. Whatever they may know of the Gospel of Matthew, they are bombarded with others: the gospel of conspicuous consumption, the gospel of Wall Street, or maybe now, just Walmart, the gospel of MTV and the sweet life. Engaging with this pluralism is disorienting and leads many to question early on whether everything their parents taught them is untrue. What is right, after all? What is wrong? What is true or false? What about God and Church? All this combined with limited life experience makes it hard to find one’s way.

When young visitors enter communities like Jayaque and Tonacatapeque, they forget their problems back home. If they have the courage to listen to those heart-rending stories I mentioned, they will experience a question welling up within them: If this is how the world is – if this is an average country – then how do I want to live my life? The wonderful thing about this question is that this is not their parents nagging about when they are going to get it together and settle down. It’s not the priest. No, it’s coming from within them. It’s their deepest voice, frequently accompanied by joy and enthusiasm which are signs that the Spirit is nudging them to take up their deepest vocation in life.

Let me dwell on that word “vocation” for a minute, since it has no place in the lexicon of our consumer culture. Capitalist society might offer us a job or a profession, but the closest thing to a “vocation” it proposes is getting and spending and just having fun. In our hearts we know that aiming so low degrades us. The temptation is to live in permanent childhood.

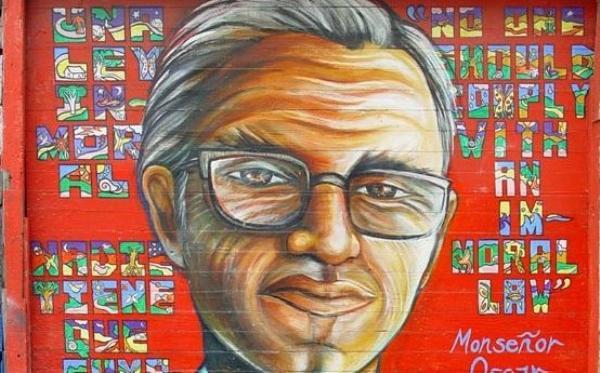

Our vocation might be to parent, to teach, to lead a social movement or a combination of such activities. But engaging with the victims of injustice surfaces the deepest vocation we have as human beings: to spend our lives in love and service. Ita Ford, the Maryknoll sister who was raped and murdered with three companions in El Salvador in 1980, wrote to her niece Jennifer a few months before she died: “I hope you come to find that which gives life a deep meaning for you. Something worth living for –maybe even worth dying for—something that energises you, enthuses you, enables you to keep moving ahead. I can’t tell you what it might be. That’s for you to find, to choose, to love.” Ita invited Jennifer to discover her deepest calling. Life is short; we only get to do it once. We can sleep through it. Consumer society is designed for dozing. Christians recognise the still, small voice that invites us to find ourselves by losing ourselves as the call of Christ. This, finally, is how God changes the world – by calling people like Abraham and Sarah, Jeremiah and Mary, Peter and Paul, Oscar Romero, Dorothy Day, and you and me.

The victims not only evoke our deepest calling. They put us in touch with the deepest mystery of our lives: the dying and the rising going on in us and around us. They reveal to us that the world is far more cruel than we usually suppose; and at the same time, they help us see that something is underway that is much more marvelous than we usually imagine, a revolution of love and goodness in the teeth of cruelty and contempt. Sin abounds, but grace abounds the more. In places like El Salvador, where we face crosses and resurrections at every turn, the coming of God’s reign sometimes seems palpable.

This is how bad things are globally: Over 100 governments today practice torture[1]; the war in the Democratic Republic of Congo goes unnoticed, while as many as 5 million die there, mostly through sickness and hunger.[2] In Darfur more than 5,000 displaced persons have been dying each month. Up to 300,000 have been killed in this Sudanese conflict and 2.7 million displaced. Poverty kills more people each year than all those who died in World War II; 963 million people are chronically hungry, and the number is rising[3]; more people (about 25,000) die daily from hunger or hunger-related causes[4] than die from terrorism in an entire year;[5] a fifth of the population lacks drinking water and basic health services; global unemployment has increased more than 20% in the last ten years and is now poised to skyrocket.[6] One billion people in rich countries receive 80% of world income, while 3 billion in poor countries receive 1.2% of total income.[7] It is a world that is organised in such a profoundly unjust way that for several decades Popes have been calling for deep changes in economic policy and political institutions.

This easily tempts us to throw up our hands in despairing resignation, or, at best try to love the people in our family and forget about the rest. But the good news overwhelms the bad for those who have eyes to see and ears to hear. As my friends on the left say, ‘¡Otro mundo es posible!’ – another world is possible! As a Christian, I want to say: This new world has already begun and it is destined to triumph. I’ve seen it in El Salvador. That’s the reign of God, God’s revolution. I mean to suggest that God is at work full-time to overcome this bad news with good news of life and love and to enable us to participate and bear abundant fruit. One palpable sign of hope is the movement of international solidarity.

Globalising solidarity.I like to invite visiting delegations to see their engagement with El Salvador as part of the worldwide movement of international solidarity that has been growing exponentially in quantity, in sophistication and in effectiveness. As national governments, even at their best, lose their effectiveness, this is one of the most hopeful signs of our times, although the media and their powerful backers seem not to notice. As markets and arms sales and narco-trafficking globalise, so, too, does solidarity. Solidarity builds clinics in El Salvador, but also campaigns to ban cluster bombs and antipersonnel mines. The Jubilee 2000 campaign and its sequels forced the G7 governments to concede debt relief to the world’s most highly-indebted nations. None of that would have been possible twenty years before, without internet, e-mail and cheaper international air travel. And notice, too, that the churches, and the Catholic Church in particular, are better positioned than anyone else to globalise international solidarity. No other organisations have the people on the ground working among the poor all over the world and, let’s hope, the motivation and tenacity to help empower the poor, resist violence and defend the environment at the grassroots level.

Besides helping the poor, international cooperation changes the visitors, as we have seen. This is crucial, because unless things change in places like Europe and North America, they will continue to go badly in places like Central America. In particular, engaging the poor of the South renews the Church in the North. I’m tempted to suggest an appendix to Pope Benedict’s encyclical Deus caritas est, which specifies that the practice of love is indispensable to church and parish life. My appendix would recommend that every parish in the North form a sister-relationship with a congregation in the poor South – for the good of all concerned.

So, as the powerful globalise markets, finance and communications, we need to globalise the practice of love and turn this violent new century into the Century of Solidarity, and to transform our civilisation based on capital into a civilisation based on people and their labour. More than anything else, this will require “new human beings,” including a critical mass of people in Europe and North America, with hearts capable of identifying with the poor majority of the planet. They must also be able to address complex issues of trade, finance and human rights law in their home countries.

Where will these new human beings come from? If they don’t come forth from the churches, I doubt anyone else will fill the need. The Church must form these new human beings with hearts of flesh. Its schools should give a privileged place to the intellectual and moral formation the world calls for.

4. Education and Formation

This brings me, a little awkwardly, to the question of formation. During the past week in Great Britain, many people have expressed concern about declining participation of young people in church life and how, despite the great need and despite generosity and creativity, not everyone in the Church embraces the cause of justice and peace as a central dimension of the Church’s mission. This seems to me a major challenge and opportunity.

While I cannot offer any solution to these problems, I think what we have already said here throws some light on them and also on how we can help form that critical mass of “new human beings” that I mentioned. For that purpose I append these final reflections. While they are partly autobiographical, they also reflect the philosophy of education that motivated Ignacio Ellacuría and his colleagues and that continues to guide us at the UCA.

In these confusing times, it is difficult to find our way, as I said, especially for young people. Like most of them, when I was in college, my own world-view unravelled, precipitating a difficult time of searching for what is true and for what I should do with my life. That searching taught me crucial lessons, most of which I could only formulate clearly years later. What I discovered was that, if we want to search with integrity for what is true and what is right, we have to attend to the three sources of truth: concrete reality, the voice within us, and the truth that comes from a wise community. Let me say something about each of these.

First, we have to face up to reality in all its starkness and beauty. Ellacuría always insisted on that, and it remains fundamental for us at the UCA. Of course, reality is vast and complex, so we must specify the priority of facing up to the drama of life and death, good and evil, oppression and liberation, sin and grace. That is the nucleus of reality, where meaning is most dense. So, we need to feel the impact of the victims, the poor, taking in how bad things are, as I said earlier –and responding to it. It is only then that we can appreciate how good things are at the same time. Life is not a spectator sport. From the sidelines we may be able to analyse the football game, but in the moral game of life we have to participate in order to appreciate what is going on. This means that we need to challenge our friends who want to interpret our situation in practical isolation from the most pressing human and environmental problems. Hot tubs are not the place from which to discern what we should do.

Since reality is too rich and complex to catch on the first bounce, contemplation is strictly necessary to assess it. So too are responsible leaps of faith, as Augustine saw so clearly. Belief in God is a crucial, illustrative case, though not the only one. It deserves special mention, I think, because it is such a hot topic in Great Britain these days. If we believe in God, that is because the evidence points in that direction, not just the measurable evidence but especially the moral, existential evidence. In that case, not taking that leap would be less reasonable, less responsible than leaping.

All this implies that pure reason is insufficient for learning the meaning of life. Much less can we reduce rationality to the empirical method of the natural sciences. In pursuit of wisdom, only reason integrally considered will do: reason rooted in reality and in ethical practice and contemplation. The exercise of reason must also be purified.

That is to say, second, that we need cognitive liberation, which entails freeing ourselves from the fears and idols that fuel our prejudices and hide our blind spots. Since these are rooted in our commitments, we need to undergo conversion. As we saw earlier when reflecting on the experience of pilgrims in El Salvador, engaging with the crosses of the poor and the victims provokes the kind of wholesome crisis that fosters cognitive liberation.

More than anything else, the conversion in question entails the basic commitment to follow our conscience as best we can and come what may. That crucial turn allows us to see straight. Above all, it allows God to work on us and to guide us via the consolation of the Spirit into the light. Reason integrally considered includes all that, too.

Third and finally, we need community to both challenge us and to support us in an alternative vision and way of life. Not any community will do for this. It behooves those of us who have only lived a few years on the planet to recognise that the human race, for all its foolishness, has collected some extraordinary treasures of wisdom to help guide us in life. So, the community we need to help us search must be a wisdom-bearing community. We need to identify ourselves, critically, with some wisdom tradition. Catholicism does that for me. With all its limitations, it has a prophetic corrective built in to it. But in any case, this seems to me a good basis on which to challenge our friends who want Jesus without the Church, who are spiritual but not religious.

It also implies that we, in church, must challenge and support one another in our searching. Since we love others, we will challenge the authenticity of their searching and welcome that kind of help from others. To what extent are we searching and discerning authentically, attentive to the three sources of truth: the truth of the creator of all reality, the truth of the Spirit who moves us inwardly, the truth of the Word who is the source of all truth and the criterion for purifying and perfecting all cultures? All three sources point us to the crucified victims who usher us into the deepest meaning of our lives, the dying and the rising. They draw us into our deepest vocation to love and serve.

I have shared with you some of the crosses and resurrections of El Salvador and Central America, which show us, I think, how the world and the Church are faring today. The deep humanity and Christian spirit of our people have fostered the commitment of our martyrs. I have tried to show how important the growing movement of international solidarity is for suffering peoples and for the Church as a whole. Finally, I have shared with you how I think we have to help people search for the truth today and how we can support and challenge one another to respond with integrity to our suffering neighbour.

May Archbishop Romero and our other generous witnesses inspire us, and may we inspire each other, to overcome our fears and idols and engage our broken world. May God strengthen the Church and make us more and more the sacrament of that new human family which has already dawned and is destined to triumph.

Dean Brackley SJ is Professor of Theology and Ethics at the University of Central America in San Salvador.

[1] International Rehabilitation Council for Torture Victims, Annual Report, 2007, p. 4; <http://www.irct.org/IRCT-Annual-Reports-60.aspx>, consulted Jan. 28, 2009.

[2] New York Times, Dec. 13, 2008, p. A5.

[3] http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/8836/icode/ (consulted Jan. 28, 2009).

[4] “Hunger and World Poverty,” www.Poverty.com, cited by Bill Quigley, “Twenty Questions: Social Justice Quiz 2008,http://www.truthout.org/article/twenty-questions-social-justice-quiz-2008

[5] “Terrorism Deaths Rose in 2007,” Voice of America, May 2, 2008; cited by Quigley, “Twenty Questions.”

[6] Eduardo Galeano, Patas Arriba. La escuela del mundo al revés. México: Siglo XXI, 1998, pp. 29-30.

[7] Lilian Vega, Cátedra Realidad Nacional, UCA, Nov. 12, 2008.

![]() Read Part One of the 2009 Romero Lecture

Read Part One of the 2009 Romero Lecture

![]() The Romero Trust

The Romero Trust