The 2009 Archbishop Romero Lecture, organised by the Archbishop Romero Trust, was delivered in venues across the UK by Dean Brackley SJ. In the first of a two-part serialisation of the lecture on Thinking Faith, Professor Brackley discusses the polarisation of the population of El Salvador, and the mission of the Church in Central America.

This is an important time for the country of El Salvador and our Church. Next November marks the 20th anniversary of the deaths of the six Jesuits and two women who were murdered at the University of Central America, in El Salvador. We will commemorate the 30th anniversary of Archbishop Romero’s death in March of next year. So, we are beginning a kind of jubilee year of anniversaries. In addition, last Saturday José Luis Escobar Alas was installed as the new archbishop of San Salvador. Finally, as the global economic crisis spreads and our ongoing regional crisis deepens, Salvadorans go to the polls next month to elect a new president. Surveys suggest that a major shift in national political life may be in the offing. As we struggle to respond to these new challenges and opportunities, we will look to the life and witness of Archbishop Romero and our other martyrs to guide us.

I want to share with you some of our pain and suffering, as well as the consolation that springs from the deep faith of our people. I also want to say a word about the growing movement of international solidarity that is such a promising sign of our times. You will see that the crosses and resurrections of Central America can inspire all of us to respond better to our broken world.

1. Overview of El Salvador: Polarisation

By world standards, El Salvador is an “average” country in an average region. We are in the middle of the U.N. Development Programme’s Human Development Index, along with most of Central America - not with Haiti, the Congo or the poorest countries of Africa but certainly not with Europe and North America. But, internally, El Salvador, like most of Central America, is a place of extremes. That makes this an ideal place to observe crucial tendencies in society, to see where the world is going and maybe where the Church is headed, too.

1.1. Economic polarisation. If I had to use one word to characterise El Salvador, and most of Central America, it would be polarisation. First of all, we are polarised economically.

As I was preparing these remarks, my friend Alfredo stopped by to talk. He is a bricklayer and can’t find work. Only 20% of the national workforce has a decent, stable job, according to a new study. Alfredo isn’t one of them. Now he can’t pay for his electricity bill or his children’s school fees. They barely scrape by on tortillas and beans and some extras his sick mother contributes. She cannot afford the surgery and medicine she needs. Alfredo is tempted to migrate to the United States, or do something more desperate. But he cannot pay the $7,000 for ‘the coyotes’ who guide migrants past rapists, thieves and murderers as they trek northward through Mexico.

Alfredo’s household is all-too-typical of the struggling poor in Central America, a region of 40 million people, where the per capita income is $7.00 a day. But, since ours is one of the most unequal regions in the world, the average person doesn’t receive anything like that. In El Salvador, which is typical of the region, the richest fifth of the population receive 56% of national income, and 21 times what the poorest fifth, including Alfredo, receives. So, in El Salvador more than 40% of the people live on less than $2.00 a day. (Last August the World Bank reported that 2.6 billion people, almost a third of the world’s population, consume less than $2.00 a day) However, prices in El Salvador are especially high. I estimate that two-thirds of Salvadorans live in poverty, and half of these, or one-third of the population, in extreme poverty.[1] When things were getting better elsewhere in Latin America, they were getting worse in Central America, where US-supported neoliberal policies followed on from devastating civil wars. For example, while malnutrition in Latin America and the Caribbean fell between 1990 and 2003, in Central America it increased from 17% to 20% of the population.[2] With the surge of fuel and grain prices in the last two years, millions more people have joined the ranks of the poor.

Social spending is abysmal and fails to alleviate the suffering. The Salvadoran government spends less than 3% of GDP on education.[3] Although young people, especially girls, now receive more education than their grandparents did, almost two-thirds of the population (64%) has not finished elementary school. Less than 15% have finished secondary schooling. More than three-quarters (78%) have no health insurance.[4] A surgeon-friend of mine who works in the main public hospital tells me, ‘We ask the government for $5 million worth of medicines for the year. That is what we need. They refuse to give us a penny more than $2 million.’ She pauses for emphasis and adds: ‘Many people die because of that.’ According to an inside source of mine, social spending is very low despite the fact that large and medium businesses typically make more than a 50% profit on gross income. Businesses massively evade taxes, which are low in any case, to a huge extent.

When I worked in the South Bronx in New York in the 1980s, I saw how the exclusion of large sectors of the population from a decent way of life produces a threefold crumbling: of communities, families and individuals themselves. In El Salvador it feels like I’m witnessing the globalisation of the old South Bronx. In today’s more urban society, social exclusion generates tremendous insecurity, rampant delinquency with urban gangs that, in tandem with organised crime, drug dealing and violence, undermine a state of law. The violence sometimes surpasses that of the civil wars in the 1980s. With 92 homicides per 100,000 young people, El Salvador is among the most dangerous places for young people in the world.[5]

In different forms,this kind of inequality and exclusion has characterised El Salvador and Central America since the Spanish conquest. The ‘safety valve’ for the social pressure generated has historically been that poor people simply died before their time, or were killed for rebelling. The twentieth century witnessed many attempts to modernise society, and the hoped-for changes served as a kind of second safety valve for historic social pressures. Unfortunately, from the very beginning, these efforts were crushed, sometimes by the United States alone, sometimes by local elites, sometimes by both together. As the century progressed, reformers grew more radical – like Fidel Castro and the leftist movements in Central America from the 60s to the 90s – and the reaction grew more brutal and violent. Today the fundamental social contradictions remain in place, and nobody expects things to change soon, even with a big change in government, as we shall see.

As a result of this situation, people are heading north, literally, in droves. The new safety valve is California, Texas and Arlington, Virginia. Hundreds abandon the country each day to make their way north. The same is true of Guatemala and Honduras, our neighbours.

Clearly, as Ignacio Ellacuría said some years ago, “It remains an urgent task in El Salvador to give sight to the blind and to set free the oppressed in a global process of liberation which continues to have the poorest and those most in need as the first ones to whom all good news is addressed.”[6] Ellacuría called for a transformation of our civilisation of capital into a civilisation based on work, solidarity and participation.

1.2. Political polarisation. Especially in countries with leftist parties and movements –Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador – politics is sharply polarised around the interests of rich and poor. In El Salvador the ultra-right ARENA party has been in power for 20 years. It is likely that elections in March will bring to power a centre-left president from the FMLN party of the former guerrillas, led by more hard-liners. The prudent choice of a moderate candidate masks the unwillingness of these hard-liners to reach out to centre-left forces. As a result, anyone who wants to oust the present government must vote for the FMLN. The result has been an eclipse of centrist parties which, in the end, favours the right. However, since the 1992 peace accords, the political opposition has gained ground, as the level of political fear subsided in most areas.

But by itself a change of government will not produce the liberation Ellacuría calls for. Even if the FMLN candidate wins, fundamental inequalities will not change soon. Politics isn’t what it used to be, especially in small countries so dependent on big economic powers and so intertwined in the broader international economic and political relations. Capital rules, even dependent capital.

1.3. Polarised Generations? A new kind of generation gap has opened up in Central America. The median age in the region is 21; in Guatemala, 19.[7] The younger half of the population is the first generation that is predominantly urban, the first generation raised universally in front of the TV set, the first exposed to modern, even post-modern pluralism and the first not to see themselves as fated to live just like their parents. From the impoverished countryside, young people typically want to move to the city to work or study or even migrate to the United States. Not that they are at constant odds with their elders, but they are more critical, more open to what is new and less sure of things.

1.4. Morally Polarised. El Salvador is polarised morally. One either opens one’s heart to the kind of suffering I have described or closes oneself to it. Ours is a region of cruel negligence of people and their needs, as I have already described, but also of great kindness, solidarity, sanctity. It is a place of death squads and of martyrs.

For inspiration consider my good friend Teresa Perez. Ignacio Martin-Baro, one of our martyred Jesuits, was pastor of her poor rural parish. At a commemorative Mass for ‘Nacho’, Teresa recalled how, after the murders in the UCA, soldiers occupied the local chapel, and some abandoned parish work in fear. Teresa, a grandmother and catechist, did not. She testified, “If death finds us here working for the Church, let’s welcome it!”

Recently I stopped by to visit her. Knowing she had been sick, I asked if she was eating enough. With grandchildren scurrying about the dirt floor, she leaned close so no one would hear. Smiling she answered, “Don’t you think it’s more important that the little ones eat?”

In Central America we live with daily crucifixions, but also resurrections, which help to bear our crosses. Grace abounds and manifests itself in deep reserves of humanity and Christian spirit, especially among the poor. This is a major source of hope in these hard times.

Those who suffer most celebrate life with profound gratitude; they share what little they have, practice hospitality and stubbornly resist the lethal forces around them. Their faith and solidarity spreads out in concentric circles, like a contagious medicine. They build up the Church, which they serve generously. They are the foundation on which to build a more human future and a more faithful Church.

2. The Church and the churches

In El Salvador practically everyone believes in God,[8] and 87% consider religion to be very important in their lives.[9] I confess that sometimes I wonder what god people actually believe in; and with the cultural transformation now underway, we dare not take the future of the faith for granted. But for now, with all its ambiguities, this religious spirit is one of the greatest riches of this suffering region.

Today 55% of Salvadorans say they are Catholic, which is low for Latin America. Pentecostal protestants made spectacular gains during the 70s and 80s, in part because Catholics were slow to respond, in the light of Vatican II and the Conferences of Medellín and Puebla, to a rapidly urbanising society, suffused with the mass media and more critical of traditional authority. Today protestants number about 29%. They are mostly Pentecostal evangelicals. Among mainstream protestant denominations, only the Baptists, with a long history in El Salvador, have a large following. During the years of political and military conflict, the Pentecostals kept a scandalous silence in the face of atrocities, while the government rolled out the red carpet for evangelicals from the US, as a counterweight to more prophetic voices, especially in the Catholic Church. In recent years, though, the leaders of two large Pentecostal groups have adopted a more sophisticated and responsible stance in the face of systemic injustice. The Pentecostal churches are late arrivals to the kind of polarisation that has characterised the Catholic Church for a long time.

Where populations are both religious and divided, it is hardly surprising that the churches are polarised, principally over the massive poverty and injustice. What does the plight of the poor majority mean for the Church? Where does their plight fit in to the Church’s agenda? Not everyone responds in the same way.

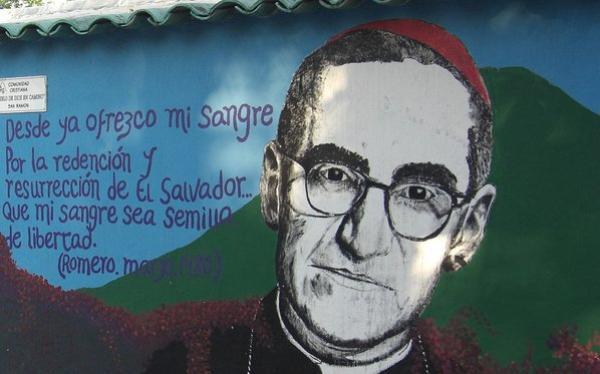

Since the Second Vatican Council, many Christians in Central America have come to understand that God is the first to stand with the poor, to take up their cause in the name of universal love, and that the faith requires that we, too, stand with them, that we be a Church of the poor. In taking that prophetic stand, the Church in Central America has been blessed with many martyrs, including dozens of priests and religious and three bishops – Monseñor Romero (1980) and Monseñor Joaquín Ramos (1993) in El Salvador, and Bishop Juan Gerardi in Guatemala (1998) – as well as a cloud of catechists and committed lay Catholics and many protestants as well. They have given the credible testimony that the 2007 Aparecida Conference (of Latin American Bishops) called for.

And yet, many in the churches find their memory unsettling. In El Salvador, as elsewhere, this prophetic vision of a Church of the poor has never been the majority view. For some, massive injustice is not a major issue for the Church, whose proper concern is the salvation of souls. However much we are obliged to feed the hungry, our job is not to criticise the institutions and practices that generate misery and exclusion. That is the task of the government and other social actors, including Catholic laypeople. But many others of us reject this reduction of the Church’s mission. For us, the poor are the crucified vicars of Christ. If we don’t walk with them, then we are not walking with him. If the message is not good news for the poor, then it is not the gospel of Jesus Christ. That vision and practice, sealed in blood, continues to shape the religious culture of country and the wider region. It must continue to leaven the whole Church, even as it evolves to face new circumstances and generational change.

In their turbulent cultural surroundings, young people suffer frequent periods of disorientation and personal crises. The majority lacks a solid Christian formation. Still, many do participate actively in Church and show up in large numbers at events commemorating Romero and the other martyrs. In a cynical and suffering world, the martyrs inspire. When the Church walks with the poor, as they did, it draws on the power of the cross and the faith appears credible. Young people respond to the good news of a credible love.

At the UCA, our theology department and the Romero Centre strive to hand on that legacy of the Church of the poor, to present and future generations, but also to the stream of visitors from abroad that seems to swell each year.

Dean Brackley SJ is Professor of Theology and Ethics at the University of Central America in San Salvador.

[1] See the United Nations Development Program, “Human Development Indicators,” in Human Development Report 2007-2008.

[2]Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación (FAO), “Estrategia para extender a escala nacional el Programa Especial para la Seguridad Alimentaria —PESA-- en América Central 2005-2009”, p. 2. (http://www.fao.org/spfs/pdf/Estrategia_PESACAM.pdf). Cfr. idem, The State of Food Security in the World 2006, p. 19 (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/bsp/hi/pdfs/30_10_06_fao.pdf)

[3] Ibid.

[4] Lilian Vega, head of the Economics Department of the UCA, “Cátedra realidad nacional. Conmemoración,” unpublished paper delivered at the UCA for the 19th anniversary of the UCA martyrs, San Salvador, Nov. 12, 2008.

[5] La Prensa Gráfica, 26 November, 2008, reporting on a new study by The Red de Información Technológica Latinoamericana (RITLA). The average rate for Latin America as a whole is 36.6 per 100,000, far higher than the second-place region, Africa, with 16.1 per 100,000 (ibid.).

[6] I. Ellacuría, “Los retos del país a la UCA en su vigésimo aniversario”, Conference delivered on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Universidad Centroamericana José Simeón Cañas (UCA), September, 1985. In Planteamiento universitario 1989 (San Salvador: UCA, 1989), p. 164.

[7] Extrapolación de United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population División, “National Trends in Population, Resources, Environment and Development: Country Profiles”, http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/countryprofile/profile.htm, consultado 10-09-06.

[8] En 1995 sólo 1.1% dijo no creer en Dios. IUDOP-UCA, “La religión de los salvadoreños en 1995”, Estudios Centroamericanos, 563 (sept. 1995), p. 853.

[9]IUDOP-UCA, “Encuesta sobre valores”, Serie de Informes 80 (sept. de 1999), p. 14.

![]() Read Part Two of the 2009 Romero Lecture

Read Part Two of the 2009 Romero Lecture

![]() Romero Trust

Romero Trust