Of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales canonised on 25 October 1970, ten were Jesuits. Among them were saints such as Edmund Campion, Nicholas Owen and Robert Southwell, whose stories are well known. Yet on the fiftieth anniversary of the martyrs’ canonisation, occurring as it does amid a pandemic, Michael Holman SJ invites us to study the life of a lesser known Jesuit martyr, St Henry Morse, ‘priest of the plague’.

On 25 October 2020, the Church in England and Wales will celebrate a significant anniversary. On that day fifty years ago, in St Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Pope Paul VI canonised forty men and women all of whom were martyred in England and Wales during the Reformation and the years that followed, between 1535 and 1679.

In his homily, the pope, while praising the martyrs’ ‘fearless faith and marvellous constancy’, noted that in so many other respects they were so different: ‘In age and sex, in culture and education, in social status and occupation, in character and temperament, in qualities natural and supernatural and in the external circumstances of their lives’. What united them all was an ‘interior quality of unshakeable loyalty to the vocation given them by God and the sacrifice of their lives as a loving response to that call’.

In 1970, I was a pupil in the Jesuit college in Wimbledon. Devotion to these martyrs was a prominent feature of school life: we were encouraged to think of them as our heroes. Stories of their lives and especially their bloody, violent deaths, were often told in assemblies and during religious education lessons. Their portraits hung on the walls of the corridors and classrooms. There was one painting which featured all forty of them, standing in their lay or religious dress around an altar underneath a gallows with the Tower of London, where many were imprisoned, looming in the background. Two of the four houses to which we belonged were named after two of these martyrs, Edmund Campion and Robert Southwell, and the others after St Thomas More and St John Fisher, martyrs who had been canonised 35 years previously.

Even as a schoolboy, I was conscious of being part of a minority Catholic community, separate from and to some extent feeling threatened by the dominant Protestant culture of the country in which we lived, and which even then regarded us as somehow foreign. I remember discussing with one much admired history teacher the number of high offices of state from which we Catholics were excluded and I was fascinated by how Catholic historians would interpret the history of the Reformation period differently from most of those who wrote our textbooks. Every Friday afternoon the whole school would attend benediction in the nearby Sacred Heart church at which we would recite a prayer for the conversion of England.

Some of these divisions were reflected in my family life. My mother was born Catholic and my father a life-long member of the Church of England. I remember the upset I felt when I was told that, as theirs was a ‘mixed marriage’, they were not allowed singing, only organ music, at their wedding and that it took place not inside but outside the sanctuary of the church. At Easter and Christmas when I was a small boy my father would take himself off to Christ Church, the nearby Anglican church, and to this day it saddens me that he always went there alone.

When martyrs are canonised, we are encouraged not only to honour what they did and how they died but to take them as models for our own lives as well. We can also ask them to intercede for us, that their virtues might be ours too. We live in happily more ecumenical times and Catholics, by and large, find themselves accepted in public life, so do these martyrs have anything to say to the way we live our discipleship of Jesus today?

This question has surfaced for me a good deal in recent months as the anniversary approached. Ten of the forty martyrs were brother Jesuits which has made the question still more poignant. What, if anything, do they have to say to my living the Jesuit vocation in a very different world? Furthermore, we have recently reorganised our seven Jesuit houses in London into one community in seven locations, a structure curiously similar to that which existed in the seventeenth century. Might our new community’s patron be found among these ten?

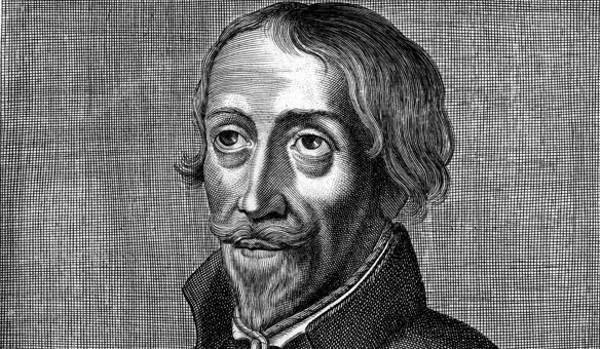

One of these martyrs has particularly caught my attention. Less well-known than St Edmund Campion, who left behind a stellar career at Oxford to become a Jesuit and priest, or the poet St Robert Southwell, or the builder of priest-holes St Nicholas Owen, St Henry Morse ministered in London and became known as the ‘priest of the plague’. As our one London community was established during a pandemic, with a number of our men engaged in work not unlike his, he appeared to be one suitable candidate for our patron.

Henry Morse was born in 1595 in Broome, a small Suffolk village less than a mile from the Norfolk border where he was baptised into the Church of England. He was executed before a crowd of thousands on 1 February 1645 at Tyburn in London. Fr Philip Caraman SJ’s biography of Morse is more than 60 years old and aspects of it have no doubt been superseded by more recent scholarship, but his account of Morse’s life is well worth reading: it is vividly told and packed full of detail drawn for the most part from primary sources. Caraman paints a picture of an unfailingly generous man who in the most adverse of circumstances served the poorest with little or no regard for his own safety and with great kindness.

Many aspects of Morse’s life raise questions. By the age of nineteen, after a year in Cambridge and another at the Inns of Court, he had taken himself off to the English College founded by Cardinal William Allen at Douai in northern France where he became a Catholic. He returned to England to settle his family affairs prior to beginning his studies for the priesthood. He was arrested, probably at Dover, and thrown into a prison for four years where he ministered to the sick. He was eventually released when improved relations with Spain led to an amnesty for imprisoned Catholics. Seemingly undeterred, he returned to Douai before being sent to the English College in Rome where he was taught by Jesuits and where he was ordained priest in 1624. It was here he conceived the idea of joining the Society of Jesus. He served his novitiate while ministering in the Newcastle area and while serving another period of imprisonment in York, where again he engaged in charitable work among his fellow prisoners, Catholic and non-Catholic alike. On release in 1628, he was banished from England and then acted as a chaplain to English and Irish troops attached to the Spanish army in the Low Countries before being sent back to England in 1633.

What was it that enabled him to defy convention and choose a way of life that was not only unconventional but which put his life at risk? What was it that enabled him again and again while in prison to turn his attention from himself to the needs of others? How was it that, despite years of imprisonment, he longed to return to England even though he knew of the dangers that awaited him there?

His freedom was remarkable. Where did it come from? Certainly, he had a strong conviction that the Catholic Church was the one true Church. Certainly too, he had an equally strong desire to be of service to his brothers and sisters whose eternal salvation, as he understood it, was at risk so long as they were separated from this Church. But especially significant, it seems to me, is what one contemporary of his in Rome, Ambrose Corby, wrote in a memoir of Morse: he was a ‘lover of the cross of Christ’. Was this love the source of his freedom? A love that led him to desire to be as closely associated with Jesus as he could be; to share Jesus’s sufferings and to be with Jesus as he shared the suffering of others?

It’s this desire to be with Jesus, wherever that love may take us, which Fr Gerald O’Mahony wrote about in the context of the third week of the Spiritual Exercises when the retreatant prays for ‘sorrow with Christ in sorrow, anguish with Christ in anguish, tears and deep grief because of the great affliction Christ endures for me’ (Spiritual Exercises §203):

I would rather

be here with you

than anywhere else

without you

I would rather

have nothing

and be with you

than have everything else

without you

I would rather

be mocked and ridiculed

with you than be living comfortably

and well thought of

without you

Morse’s freedom was much in evidence when he was sent by the Jesuit superior in London, Fr Matthew Wilson, to work in the area of the parish of St Giles in the Fields, near present day Tottenham Court Road station and to the south of Bloomsbury, then a poor and densely populated area of London. His ministry amongst the plague victims was undertaken together with the secular priest John Southworth, also one of the canonised martyrs whose body now lies in the Chapel of St George and the English Martyrs in Westminster Cathedral. He began with some days of prayer in a Jesuit rest-house near the village of Cheam in Surrey, an hour’s ride from London.

Morse arrived in St Giles in the spring of 1635. It was with the coming of warmer weather in April that the extent of the outbreak of plague was recognised as more than a minor occurrence. Reading Caraman’s account, one is struck by the at least superficial similarities of conditions then with those that mark today’s pandemic. The best scientific advice was followed, as then supplied by the Royal College of Physicians. Plague victims and their families were placed in strict social isolation; others avoided eating and socialising with them lest they caught the plague. With visiting forbidden, loneliness became a problem. Business collapsed and unemployment increased with consequent lawlessness. Some refused to report their illness and failed to isolate, and consequently the plague spread and the number of victims increased. Theories about the cause of the plague abounded. Some ‘conversed with the infected’ to find out ‘the nature, origin and way of curing the plague’, while others saw it as the judgment of God with puritan preachers blaming it on papist idolatry.

Morse and Southworth set about bringing relief both to Catholic families, who were denied support from the Anglican parishes, and others as well. Funds needed to be raised for food, medicines and clothing. This required considerable organisational skill and a special committee was established for the purpose. The first to be asked to contribute were wealthy Catholics in London. Collections were then extended to Catholic congregations throughout the country. The principal donor was the Catholic Queen Henrietta Maria. Elizabeth Godwin gave testimony to Morse’s work at his trial: ‘I being a poor labouring woman never did or was able to keep a servant, and being shut up seven weeks, buried three of my little children, which Mr Morse relieved with Her Majesty’s and divers Catholics’ alms’.

It was the personal nature of Morse’s ministry which, it seems, made the deepest impression. Each week, a list of the sick was presented to the parish from which Morse made his own. When visiting their houses, he wore a mark on his clothing and carried a white stick so that others could avoid him. ‘All the while he was in close contact with the plague-stricken’, wrote Fr Alegambe, one his first biographers, in 1657, ‘entering rooms infected with foul and pestilential air, sitting down on a bed in the midst of squalor of the most repulsive and contagious nature’.

Surprisingly, perhaps, Fr Southworth complained of the ‘unworthy timidity of his companion’. Morse did not at first touch the victims he visited, administering confession and communion but not extreme unction. Morse accepted the rebuke and thereafter gave all three sacraments to the dying.

Morse’s care for the sick and dying is all the more remarkable as he himself caught the disease. He was cared for by a Catholic, Doctor Turner, who massaged the boils on the priest’s body and then lanced them. When Morse complained of the risk Turner ran by treating him in this way, Turner replied that it was his duty to serve personally a priest who had devoted himself to saving the lives of the poor.

His care extended to the dead as well, at a time when they were denied the rituals of the Church, and bodies were removed by night on carts and tipped into common graves. He would sit with the dying, close their eyes after death, wash and layout their bodies and bless them before burial. It was said of him that it was his kindness that prompted men and women to seek repentance, and kindness that won many converts.

It was on the charges of being a priest and of winning converts, thereby withdrawing them from their faith and allegiance to the king, that Morse was arrested in August 1636. When he was found guilty of the first charge, he thanked the judge ‘from the bottom of my heart’. Of the second he was found not guilty. On 23 April 1637 he made his solemn profession in prison before Fr Edward Lusher who was so inspired by Morse’s example that he himself cared for the victims of the Great Plague in London nearly 30 years later and died from the infection.

Morse was released from prison never having been sentenced on the first charge following the intervention of the king. He left the country, served as a chaplain to an English regiment in the service of Spain and returned to England for the last time in 1643. Another period of imprisonment in Newcastle and Durham followed, and once again Morse ministered to his fellow prisoners. In January 1645, he was arraigned before a court and sentenced to death on the first charge of which he had been found guilty nine years before.

In the early morning of 1 February, Morse celebrated his final Mass in Newgate prison and bade farewell to his fellow prisoners. He was then dragged on a hurdle through the streets of London and, with the noose round his neck, he struck his breast three times as a sign to a priest in the crowd to give him final absolution. ‘In the presence of an almost infinite multitude looking on in silence and in deep emotion’, wrote Ambrose Corby, ‘died Fr Henry Morse, a saviour of life unto life … upright sincere and constant. May my end be like his’.

I found myself physically moved by Caraman’s account of Morse’s last morning and death. It was as though I had lost a friend. A friend, maybe; but a model, a patron?

A younger Jesuit said to me recently that for him there were two qualities at the heart of a Jesuit vocation. These were ‘obedience’ and a commitment to the magis: doing willingly whatever our superiors ask us to do and always giving it our best. Morse is certainly an outstanding example of both, as he surely is of that quality often identified in him, kindness. Morse shows us all what kindness is: going to the help of those who are poorest, bringing that help with tenderness and compassion, paying attention to the organisational matters without which that help is not possible, focussing more on their needs than on our own safety while all the time seeking to bring about in those whom we help a reconciliation, a closer relationship with Jesus. Without this our kindness is not complete and Morse shows us that it is this very kindness which the Lord uses to bring reconciliation about. As my younger Jesuit friend also reminded me, love always begets love.

What accounts for the quality of this man’s life? We can point to his love for Jesus on the cross: his desire to be with Jesus, to become like Jesus, to go with Jesus wherever Jesus went. But I wonder if his gratitude is not more fundamental still. We get a glimpse of this gratitude of his in a prayer he wrote shortly after Fr Lusher had received his solemn profession in prison:

May God grant that while I live I may never cease to act in a manner worthy of this high honour which I acknowledge I have done nothing to deserve from his hand and providence; and may I bear always in my heart the testimony of my gratitude, and, as long as I live never cease to give thanks for it, if not by the increase of good works, at least by the desire to accomplish them.

Today we are all walking through very strange times when we need the example of men and women who can help us find meaning in what is happening. St Henry Morse, priest of the plague, is one such outstanding example. He encourages us to respond to events happening around us in the spirit of Jesus by making the most of the opportunities we are given to serve those who have least with generosity, with compassion and with his hallmark kindness, knowing that thereby we may bring them closer to God. His inspiration reaches across the centuries.

St Henry Morse, pray for us!

Michael Holman SJ is a former Provincial of the Jesuits in Britain and is Acting Superior of the London Jesuit Community.