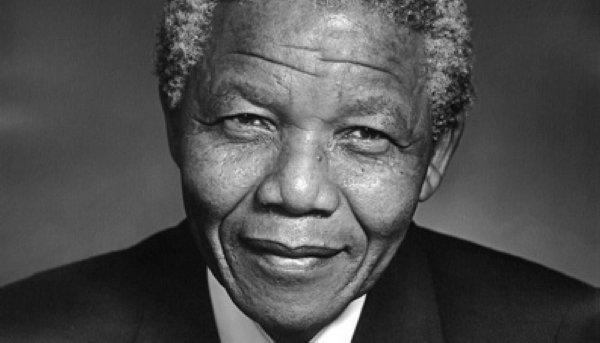

As the world learns of the death of Nelson Mandela, Thinking Faith asks two South Africans to reflect on the life and legacy of a great leader. Frances Correia and Fr Peter-John Pearson tell us what Madiba means to them.

Frances Correia

I was 16 when the ANC was unbanned. We were sitting, appropriately, in our History class and suddenly over the school loudspeaker they began to play FW de Klerk’s speech from the radio. As a Catholic school we were, by South African standards in 1990, very unusually multi-racial. In fact, Sacred Heart College had a number of children and grandchildren of struggle activists who were in hiding, in exile or in prison. As we started to realise what we were listening to, some of us began to cry. The hoped-for, but undreamed-of, end was in sight.

My memory is of it being a very solemn day: the sudden about-face of the Nationalist party caught many on all sides of the political spectrum by surprise. I also remember people immediately analysing what de Klerk had said, looking for the hidden sting in the tail and wondering what the unsaid compromise was that had resulted in this day.

In the months and years afterwards, it became common knowledge that the Nationalists had been attempting to negotiate with the ANC and especially Mandela for many years prior to 1990. Mandela had been offered compromised and compromising changes to legislation with his own freedom as the bait. This is what anti-Apartheid activists feared but it was consistently rejected. When we saw the complete dismantling of the legal apparatus of Apartheid, the recognition of true equality before the law of all South Africans, we saw also Mandela’s own personal commitment to accept nothing less than justice for all.

Since his release from prison, Mandela has been loyal to all the people of this country. He took the responsibility for leadership of all South Africans – those who had voted for him and longed for what an ANC government would mean, but also those on other sides of South Africa’s political fences. His presidency was marked by his deep courtesy and a profound desire for healing and reconciliation.

One of the words that defines Mandela for me is loyalty. He was profoundly loyal to the people of South Africa, to the ideals of the ANC, and to all who had been in the struggle movement. Reading between the lines of his alienation from de Klerk, it seems that Mandela felt personally betrayed by de Klerk in the negotiation process. He trusted in personal relationships and was appalled by de Klerk’s blatant political manoeuvring. In the years since his presidency, many political analysts have criticised him for being somewhat naive in his loyal appointments of those who had been in the struggle with him. The loyalty that was for me his greatest strength was seen by some to be a weakness.

Yet it is a weakness that I am glad we, as a country, have had. As we celebrate his life, as we mourn the death of a leader, who was also Madiba, father of this new nation, we are expressing our deep need for heroic leadership. We are like sheep that have lost their shepherd. Mandela, our elder, dies leaving us with the challenge to live as he lived; with integrity, loyalty and compassionate love.

Frances Correia works at the Jesuit Institute, South Africa.

Fr Peter-John Pearson

One of the rather touching aspects of the time over which anxiety mounted over the health of former President Nelson Mandela was the way in which everyone felt that they were witnessing the closing chapter of a loved one, a family member. So many conversations in diverse situations begin with ‘When I saw Mandela’ or ‘When I met Mandela’ – even if that meeting was somewhat vicariously over the television or in newspaper pages, it remained somehow personal.

I met Mandela a few times, mostly in a reception line or as a part of a delegation, and on each of those times the same things struck me. He invariably said how honoured he was to meet you; he took his time with each person, holding their hands, his eyes focused on the person in front of him; his old world charm and manners made you feel so special. If you happened to be wearing a clerical collar he inevitably spoke of his deep respect for the Church, of how the Church provided for his early formal education and how, were it not for the Church, he and many of his generation would not be where they were. He was generous in his praise for the Church’s role in the fight against apartheid.

It was one of his quite remarkable characteristics that he never forgot a personal kindness and remembered the generosity of others. We saw this when he visited Ireland: in the midst of a busy state visit schedule, he traced a former chaplain to Robben Island, Fr Brendan Long, to his hospital bed and spoke with him over the phone, reminiscing about life on the island and thanking Fr Long for his years of service, graciousness, generosity and kindness. Those indelible marks of the Spirit certainly showed forth in a most unselfconscious way in this former prisoner.

I have another memory of a church encounter with Mandela. In the days running up to the first democratic elections, he, with friends and colleagues (and no doubt with an eye on the upcoming elections!), attended Mass in the Capuchin-run parish church in Athlone in Cape Town, in what was designated a residential area for ‘coloured people’ in the old apartheid parlance. It was a church which had been a focal point in the struggle against apartheid, which made his presence there all the more poignant.

In his dignified manner, Mandela joined the line to receive Holy Communion from the hands of Archbishop Henry, even though he was not a Catholic! He received Communion reverently and afterwards, when questioned about this rather unexpected gesture, he spoke of the need for spiritual sustenance in times of great challenge! Unbeknown to him, his answer seemed for many to indicate an intuitive grasp of an important aspect of Eucharistic theology.

Whatever Mandela’s own theological understanding might have been, the occasion did underline his deep sense of the power of the spiritual life. This can also be glimpsed in his writings: from his days on the hills of his hometown as a young herdsman, to the long years of imprisonment, he had learnt, consciously or unconsciously, the truth that Paul enjoined on the Corinthians as a source of reassurance and as a lodestar for the future: that where the spirit is, there is freedom. Something of the greatness of Mandela’s extraordinary legacy is surely rooted in this abiding truth.

Fr Peter-John Pearson is the Director of the Parliamentary Liaison Office of the Southern African Catholic Bishops’ Conference.