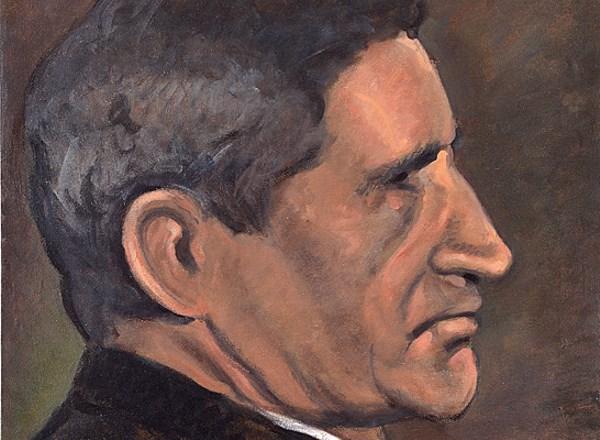

The penultimate Jesuit in the 2014 calendar produced by the Jesuits in Britain is Blessed Rupert Mayer. After serving as a chaplain in the First World War, he became an outspoken critic of the Nazis, which led to his imprisonment on more than one occasion. Peter Knox SJ tells us more about the ‘Apostle of Munich’ who cared deeply for the poor of that city and left a deep impression on its residents.

The first time I visited my grandparents in Bavaria, my grandfather, then in his eighties, took me into Munich to see the sights. After the mandatory stops in the cathedral and the neighbouring Jesuit parish of St Michael’s, we went into the basement of the town hall. There was a stream of people laden with their shopping bags quietly going in and out. It was strange to see candles in the town hall and to hear such reverential silence. But of course the people weren’t coming to pay their electricity bills in the basement. They were coming to pray at the tomb of Rupert Mayer, Munich’s 20th Century saint. Because of the stream of people coming to venerate him, Rupert’s remains had been transferred from the Jesuit cemetery in the suburb of Pullach to the city centre. Some 38 years after his death, Blessed Rupert was still drawing a daily crowd of thousands. The only other place I have seen such posthumous veneration is at the tomb of Pope John Paul II in the crypt of St Peter’s Basilica.

After spending some time at the tomb, we went out into the busy city centre. My grandfather told me something of the life of Rupert Mayer, a prominent figure during his youth in the city. In the fashionable streets of Bavaria’s capital it was difficult to imagine the same city populated with indigent people needing a full-time chaplain. But between the Hauptbahnhof and Marienplatz, queues of people would wait for hours outside St Michael’s Church to speak to Fr Mayer. This was in the Weimar Republic, when the German economy had folded after France insisted on imposing the crippling settlement conditions of the Treaty of Versailles which compelled Germany to repay millions of American dollars it could ill afford. In 1923 hyperinflation was the order of the day, and 1929 saw the Wall Street Crash. Impoverished citizens of Bavaria came flocking to Munich looking for a means to survive.

Having been appointed to work with these refugees, Rupert personally collected and distributed food and clothing, and found jobs and accommodation for the homeless and desperate. Serving Christ in the poor of his day, he was not naïve about the possibility of being taken for a ride. He said, he would rather be deceived into helping nine people who didn’t really require help than risk turning away a tenth person who was in real desperation.

Behind the prosperous façade of boutiques and pavement cafés, the city still has a less well-to-do underbelly. The homeless and the substance-dependent still hang around the Hauptbahnhof waiting for a meal or a fix. Fleiss (hard work) is not enough to guarantee prosperity in tough economic times. To this day, charitable societies founded by Rupert Mayer or named after him still serve the poor and those in need in Munich.

Rupert was born in Stuttgart in 1876 to a family of six children. He trained as a diocesan priest and was ordained at the age of 23, and joined the Jesuits the following year. After completing six years of further Jesuit training, he criss-crossed The Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany giving retreats to laypeople. In 1912 he began his life’s work with the poor of Munich. This apostolate continued until his death in 1945, apart from his period as a volunteer military chaplain in the First World War and extended periods of incarceration for his outspoken opposition to Nazi ideologies in the 1930s and ‘40s.

As chaplain to Bavarian forces during the First World War, Rupert turned down the position of working in a field hospital, opting rather to be a consoling presence to soldiers on the front lines. In the trenches of the battlefields in France, Romania and Poland, Rupert inspired and consoled men to whom he ministered, Catholic and Protestant alike. He was known for his bravery under terrifying conditions. His major tasks as chaplain were to celebrate the sacraments – particularly the Eucharist and Reconciliation, preparing men for their likely deaths – to care for dying men and then to bury countless soldiers. He was also known for rescuing injured men from the line of fire. In March 1915, Rupert was awarded the Iron Cross, 2nd Class, for his exemplary valour, the first time this recognition was bestowed on a chaplain.

In 1916, in Romania, Rupert’s left leg was shredded by shrapnel from a grenade and had to be amputated. Using a prosthesis, Rupert limped for the rest of his life, not unlike St Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit order, who as a young soldier had his leg shattered by a cannon ball in the siege of Pamplona. The leg was to cause Rupert great suffering in his subsequent years of pilgrimages and processions, earning him the nickname of the ‘limping priest.’

Returning to Munich after World War One, Rupert resumed his ministry of caring for the poor of the city. Inspired, perhaps, by his namesake, Saint Rupert, the 7th Century apostle of Bavaria, Rupert Mayer built up not monasteries, but associations of laypeople to bring Christian compassion to Munich. For example, during his time as the chaplain to the Men’s Congregation of Mary, its membership doubled to over 7000. People who came to him found an understanding priest who was suffering in a similar way to them. He dispensed not only food and clothing, but also realistic spiritual advice and was a renowned preacher in particular demand in the confessional

In the inter-war period Rupert not only served the poor of the city, but extended his ministry to whoever needed it. My grandfather, at the time a young man in Munich, told me how he would sometimes encounter Fr Mayer on Sundays, celebrating Mass at the main train station at 3:10 and 3:45 a.m. so that people who could afford a day out in the countryside would be able to fulfil their Sunday obligation before the departure of the first train.

Perhaps his experience of so much carnage and pointless death in the trenches of World War I gave Rupert a loathing for any ideology of hate. With equal vehemence he denounced both communist and national socialist programmes to which Germans in the 1920s and 1930s were turning in ever greater numbers in their economic crisis. The Weimar state was weak and extremist voices like Hitler’s promised a resurgent, prouder Germany. It took a strong character to speak out against such populist ideology. Rupert’s forthright denunciation of the Nazis’ attempts to close church schools made the government of the day ban him from preaching. But he continued to do so, and in 1937 received a six-month suspended prison sentence. Still continuing to preach, he was silenced by church authorities anxious not to incur the wrath of the state. But after the Prefect of Munich made a particularly defamatory statement, Rupert’s superiors allowed him to preach again in public. For this he was promptly arrested and imprisoned in Landsberg Prison, where, in a twist of irony, Adolf Hitler had been imprisoned after his abortive 1924 Beer Hall putsch, and where, after World War II, hundreds of condemned war criminals were executed. Five months later, upon his release from Landsberg in a general amnesty, Rupert continued to spread Christian doctrine and to denounce Nazi ideology in small discussion groups.

I find it interesting that as a former military chaplain Rupert seems not to have denounced military build-up during that period, as his contemporary Albert Einstein did:

The worst outcrop of herd life [is] the military system, which I abhor. That a man can take pleasure in marching in fours to the strains of a band is enough to make me despise him. He has only been given his big brain by mistake… Heroism on command, senseless violence, and all the loathsome nonsense that goes by the name of patriotism - how passionately I hate them! How vile and despicable war seems to me!

… words that inspired me as a young South African expected to participate in the proxy ideological wars being fought out in apartheid Southern Africa.

After the outbreak of World War II, Rupert was incarcerated in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside Berlin. My grandfather had taken me to visit Dachau, and I subsequently went to Sachsenhausen to see where Rupert had been held captive. I marvelled at how harsh, heartless and efficient the Germans had made this British invention of the South African War. As half-Jews, my relatives were held in some of these camps and forced to work in munitions factories. Unlike millions of others, they escaped with their lives. My grandfather’s brother, Franz, an art dealer, was imprisoned during the war for helping Jewish people to sell their treasures.

While in Sachsenhausen, Rupert’s health declined steadily. The Nazis, not wanting a high-profile martyr on their hands, transferred him to house arrest at the Benedictine Abbey in Ettal in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the Lutheran theologian and pastor, was also a guest of the abbey during the winter of 1940. He, however, was less fortunate than Rupert Mayer and was executed in Flossenbürg concentration camp just 23 days before the German surrender in April 1945. Rupert stayed in Ettal from August 1940 until his release in May 1945, when he returned to a devastated Munich and died of a stroke while celebrating Mass on 1 November 1945.

During his various incarcerations, Rupert was particularly concerned that his silence may be misconstrued by the faithful as capitulation to the Nazi demands that he stop preaching against the state. The churches in South Africa could also not afford to concede to the state. Victimising Jews, communists, homosexuals, foreigners, intellectuals, church people, conscientious objectors or artists, and blaming them for national woes is not too dissimilar from what the South African government was doing under apartheid. Rupert’s was a voice of uncompromising rejection of anti-Christian ideology, that made the sometimes mealy-mouthed official church line seem a bit timid. Prophets like Archbishops Desmond Tutu and Denis Hurley OMI of Durban are equivalent voices for my time, also persecuted for their outspoken condemnation of similar hateful ideology. Bishop Kevin Dowling CSsR of Rustenburg is also known for his bravery and loving care for people with AIDS, advancing church teaching on a subject that touches the lives of millions of people across the world.

It pained Rupert that he was isolated and unable to minister to his suffering compatriots. The beauty of Ettal was no substitute for being able to care for the urban poor of war-torn Bavaria. Rupert’s zeal for the poor has challenged me often as I have grown weary of feeling that I am being taken advantage of in our parishes in Soweto, Braamfontein, or Stamford Hill or now on the streets of Nairobi. Rupert wouldn’t allow this weariness deter him from caring for the next person who came to ask for help.

Two other things from the life of Rupert strike me particularly as I now teach Vatican II to scholastics in Nairobi: firstly, throughout his life he anticipated this greatest of Church councils in promoting the apostolate of the laity. Rupert was unable to take care of all of the poor who came to him. Rather, he helped lay people to grow in their spiritual life, not only developing adult prayer lives, but directing this in an apostolic care for the poor. This was taken up by the fathers of Vatican II in their decree on the Apostolate of the Laity.

Secondly, Rupert’s ministry to soldiers of all or no denominations was a feature of the world wars, and was later a motivating force for the ecumenical movement. If one could pray in the trenches with Christians of other persuasions, why not in church in peacetime? This insight eventually paved the way for the decree on ecumenism at the Second Vatican Council.

Rupert’s dying words were ‘The Lord… The Lord…’ Was this the start of his beatific vision? Or a summary of his apostolic endeavours in caring for the poor? Or both?

Peter Knox SJ