‘Both sides are kissing their relics and ignoring living men’. So wrote Daniel Berrigan SJ of Christianity and Marxism in a letter to his brother, Philip, on Christmas Eve 1963. The comment captures the spirituality and convictions of both men. They shared a profound desire that Christianity resist the distractions of clericalism and be constantly and fundamentally concerned with changing human realities, materially and spiritually.

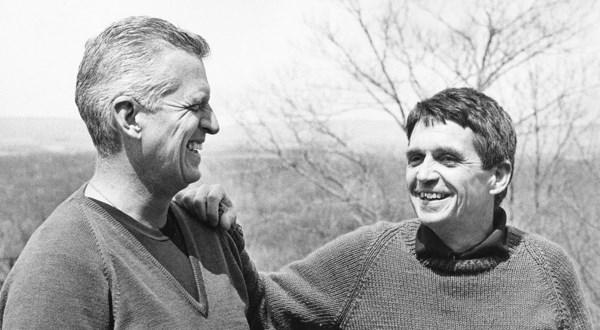

Daniel Berrigan, a Jesuit priest who was celebrated as a poet and peace activist, was born in 1921. Philip, two years younger, was similarly famous for his peace activism; he too was a priest, until he married in 1970. This new collection of their correspondence, edited by Daniel Cosacchi and Eric Martin, was in planning well before Daniel’s death on 30 April 2016, and contains excerpts of letters sent between the brothers across a stretch of seven decades until Philip’s death in December 2002.

Reading the letters is a moving, even meditative, experience, and only partly because of the things the brothers discuss. What resonates most is the intimacy with which Dan and Phil write to one another. Immense love and care fill every letter, as much at moments of misunderstanding or confrontation as at birthdays and anniversaries. Most letters give thanks for their presence in each other’s lives. In the introduction, the editors quote Dan: ‘I find it very hard to separate Phil’s fate from mine, as a matter of affection and existence itself. I wouldn’t know where his life began and mine ended’.

This deep intimacy is the great gift of the letters. As the editors say, ‘this book is a story of mutual love more than anything else’. That love penetrates every aspect of the brothers’ writing, right down to the sign-off. ‘I love youse’, writes Philip, or ‘With mucho love’. It is in the playful spelling, too. Dan writes in June 1978 to tell Phil, who is in prison:

I hope you are receiving some books regularly, today I sent Flannery O’Connor a coupla books of pomes. Plus Simone Weil…

Yestidday was pretty good. We had some 400 arrests, the pooolice were on their best behaviour. Citations for ‘disorderly conduct’. I marched with the Cath. Worker, who were in full force. Prior to that we had a mass at a good Franciscan house for street women on 40 st. It was jammed, just like the ol days.

As well as O’Connor, the Berrigans knew Dorothy Day and were close friends with Thomas Merton until his death in 1968. I would love to know which book of Simone Weil’s Daniel sent to O’Connor: I imagine him responding strongly to Weil’s L’Enracinement (‘The Need for Roots’), especially in its concern to replace the discourse of ‘rights’ with that of ‘obligations’. Recognition of the obligations humans have to treat one another humanely is a recurring theme throughout the letters, for both Phil and Dan, who share a deep desire to reanimate the Church so that it holds love of the vulnerable at its centre.

Cosacchi and Martin have put together an edition of letters that offers fascinating insight into the spiritual, moral and political worlds of the two brothers. The trouble with any selection is that it leaves tantalisingly open the question of what is missing, and it would be helpful to have more information on how the editors made their choices as well as more guidance on the letters they have included. Sometimes it is not clear which brother is writing (‘Dear Bruv’; ‘Love, Bruv’) or what is being discussed.

Yet that hardly matters when the letters offer such a strong example of what is meant by ‘brotherly love’. ‘You are never out of my Mass’, writes Dan to Phil in 1954, two years after the former’s ordination to the priesthood. Dan joined the Jesuits straight out of high school and the early letters show his concern that Phil also find his vocation, that he discover or create a path along which he can devote his gifts to others. In a letter from 1942, when he was 21 and Phil not yet 20, Daniel writes:

The spiritual advantages you have at your disposal are magnificent; and make full use of them. You have so much power at your beck and call to pray for all – for great, far-reaching good. And pray for me. I need more of the aid and strength of supernatural oneness with our Lord. You see, my boy, a Jesuit is not in existence for himself – he is an instrument of our Lord sealed and set apart as the servant of men – to bear their burdens and forget his own.

It is an extraordinary statement from one so young, and it fits entirely with the spirituality of both men, which is what stirs their peace activism. As the quote I began with demonstrates, the brothers’ fight is as much against distortions of Christianity that manifest as distractions from what really matters, as it is against a government intent on war.

Both brothers were imprisoned numerous times for their radical anti-war protests and advocacy of non-violence. Phil spent about eleven years of his life in prison, and was last in prison less than a year before his death from cancer. But the letters that most attest to hardship are the few in which the pair argues. In one notable exchange, when the brothers are in their late sixties, it is clear both that they cause each other profound pain, and, significantly, that they struggle for genuine loving reconciliation even in the midst of confrontation.

Here is Phil, in June 1989, writing to Dan after an argument in Berlin, expressing admiration and frustration:

I approach working with you in reverence. Need I spell that out? You are the best interpreter of God’s Kin-dom and the life of our Lord in the Engl. speaking world – mebbe in the world itself. And your life solidly backs your eloquence. As for me – and perhaps here my ego speaks – I would prefer being treated by you as an equal. In my sight, perhaps not in God’s, I have expended as much for peace as you have.

But Dan’s reply refuses Phil’s terms altogether. He expresses bafflement at even the notion of competition between them, asking, ‘What in me offends you?’ In line with his Ignatian spirituality, Dan’s response is a ‘long review of conscience’, trying to see, ‘In what had I offended my brother?’

How could it be, I tormented myself, that two brothers, who so love and respect one another, could have such different views of the same events, – almost as though they were receiving and sending signals from two planets? I am dumbfounded.

Dan’s suggestion is that Phil’s letter has fallen prey to a logic incompatible with the conviction that it is love, properly understood, that gives meaning to their lives. He writes, ‘Dear brother, there’s a certain violence that afflicts you’, offering a poised and deliberate reminder to Phil to honour the best of their relationship, and not to be drawn into a more cynical mode of assessing their relative merits and accomplishments. The editors do not provide Phil’s reply, and it is not clear if there is one; the next letter provided, from September of the same year, makes no reference to the dispute.

These letters are painful to read, as well as humbling. Anyone who has caused profound hurt to somebody they love, with neither desire nor intent, will feel it sharply in reading them. It is worth recalling that the exchange follows years of the closest form of mutual support, each man leaning heavily on the other. Their argument comes as a shock to both brothers – a reminder, if one is needed, that we are most vulnerable to those we most love. That is where the challenge to think again, to think anew, in Dan’s reply to Phil, is the most honouring and loving response he can give to his brother. He calls for a different logic altogether. Neither apportioning nor taking blame, Dan’s letter nevertheless urges Phil to an honest self-confrontation. He stares with unnerving concentration at their shared pain, without withholding reconciliation or love, in the very act of recognising his frustration and hurt.

The letters are equally valuable for their expression of the desire that the Church rediscover its true essence, which will also be its true calling. Dan refers to a ‘priest worker’, Père Magand SJ, who works in the factories with other workers in an act of communion and out of a desire to understand other lives, not unlike that of his compatriot, Weil. Berrigan admires the way Magand,

spoke with real passion, not so much on his own job, as on the need of charity, of justice, of poverty. It was unforgettable. He had come in on the evening train, in his old workers clothes, spoke to us in the same, even said Mass in them, without a cassock. He also brought to mind many things which have been simmering with me for some time; spoke for example of the ‘irreality’ of French Catholics, in the sense that that so d- much theorizing, analyzing, orating, is done about conditions – and so little action. This is true of their churchmen as well; for whom elan, milieu, incarnation, esprit, and all the rest become after a period of genuine freshness, a series of wearying catchwords as old as the clichés they began by replacing. And that is why the priest workers represent such a marvellous and sacrificial and admirable departure; they are one of the few steps taken to put a tether on all the billowing theory and drag it to earth.

Attending to the realness of things, to ‘earth’, is what it is all about for the brothers. A 1965 letter from Dan lists the concerns demanding his attention: ‘How to reach the outside is, for clerics, infinitely more crucial than retaining irrelevancies inside’; ‘One way of reaching outside is to make all sacred activity an immediate outside activity’; ‘for the present, clerics have responsibility to listen + learn much more than to speak or teach’; ‘the real job is in the world’.

Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises are behind many of these concerns. Three united questions resonate through the Exercises: What have I done for Christ? What am I doing for Christ? What ought I to do for Christ? In that same 1965 same letter, Daniel asks, wonderfully, ‘Who are the people who are forming the world by sacrificial action + what can we do with them?’ ‘What is the form of the cross for adults in the world?’ ‘How much of the world can we afford to be ignorant of at the hour of our death? Presuming we are to meet a Christ who came, died, rose in + for the world, not for, in, us?’

Reading the letters of the Berrigans during the close of the Year of Mercy, as I was, offered a particular awareness of moments of powerful affinity between the spirituality of the brothers and that of the present pope, who writes in Misericordiae Vultus: ‘Mercy is the force that reawakens us to new life and instils in us the courage to look to the future with hope’ (§10).

It is absolutely essential for the Church and for the credibility of her message that she herself live and testify to mercy. Her language and her gestures must transmit mercy, so as to touch the hearts of all people and inspire them once more to the find the road that leads to the Father.

The Church’s first truth is the love of Christ. The Church makes herself a servant of this love and mediates it to all people: a love that forgives and expresses itself in the gift of one’s self. Consequently, wherever the Church is present, the mercy of the Father must be evident. In our parishes, communities, associations and movements, in a word, wherever there are Christians, everyone should find an oasis of mercy. (Misericordiae Vultus, §12)

Rowan Williams writes something remarkably similar in Being Christian. Baptism, he says,

means you might expect to find Christian people near to those places where humanity is most at risk, where humanity is most disordered, disfigured and needy. Christians will be found in the neighbourhood of Jesus – but Jesus is found in the neighbourhood of human confusion and suffering, defencelessly alongside those in need. If being baptized is being led to where Jesus is, then being baptized is being led towards the chaos and the neediness of a humanity that has forgotten its own destiny. [...] A baptized Christian ought to be somebody who is not afraid of looking with honesty at that chaos inside, as well as being where humanity is at risk, outside. So baptism means being with Jesus ‘in the depths’: the depths of human need, including the depths of our own selves in their need – but also in the depths of God’s love; in the depths where the Spirit is re-creating and refreshing human life as God meant it to be.

Note that he says, ‘ought to be’. Like the Berrigans’ letters, the words of Pope Francis and the former Archbishop of Canterbury exhort Christians to movement, to changes of hearts, a newness of vision, as is meant in the original meaning of what we usually translate as ‘repentance’: μετάνοια. The word might also be translated as a change of heart, a transformation, seeing newly. Francis points out that, ‘mercy is also a goal to reach and requires dedication and sacrifice’; it requires ‘silence in order to meditate on the Word that comes to us’ (Misericordiae Vultus, §13-14): the kind of contemplation that expresses itself in action. Christianity means trying to change things on earth, now, allowing a renewed vision to infiltrate the mistaken idea that things are the way they are, and cannot be otherwise. The Berrigans both call for Christians to think rigorously about how they can do this, like Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who emphasised in Human Energy: ‘The whole question is how to liberate [suffering] and give it a consciousness of its significance and potentialities’.

For the Berrigan brothers, the Church’s job has to be in ‘the real world’ or it is failing. In that remarkable 1965 letter, Dan asks:

Is our freedom a fidelity 1) to those struggling, who cannot meet our eyes, largely because of what we have done to them, and 2) those without who have forgotten we exist? I think both... Is ‘to be forgotten as existing’ not a good definition of who we are – can we start from there?’

He ends the letter: ‘I think we are obliged only to what we see – as a maximum, not as a minimum – which is to say, our poverty + stupidity + alienation + sickness as the only riches we can claim’.

The letters are fascinating, both as historical documents and as expressions of modes of thinking that are very much needed today. Cosacchi and Martin are to be thanked for bringing these letters into the public domain. I hope more will follow.

Emily Holman recently completed her doctorate in literature at the University of Oxford