It has been reported in recent months that there has been significant progress in the cause for the canonisation of Oscar Romero, the Archbishop of San Salvador who was assassinated in 1980. Julian Filochowski, Chair of the Archbishop Romero Trust, pays tribute to the man who is already recognised as a saint by many in Latin America and beyond, and so will be remembered today, All Saints’ Day.

It would be wrong for me to anticipate the mind of the Church, but I personally believe that one day Oscar Romero will be declared a Saint of the Church.

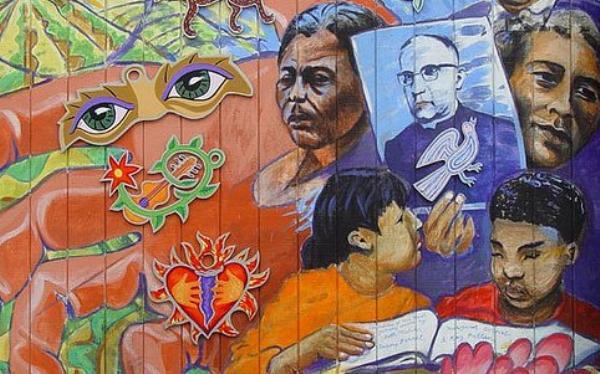

These were the carefully-chosen words of Cardinal Basil Hume in a tribute to Archbishop Romero at a memorial service in Westminster Cathedral the week after his assassination in March 1980. Thirty three years later, after many inexplicable delays, Oscar Romero is undoubtedly moving towards sainthood. The cause for his canonisation was reportedly ‘unblocked’ by Pope Francis in May and is now progressing quickly; and the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has said that there are no doctrinal obstacles to the cause. A formal certification of Romero’s martyrdom and then his beatification seems to be on the cards for 2014 or 2015, well before the centenary of his birth in 2017. Nevertheless we should remember that the Christian communities, the People of God in Latin America, long ago ‘canonised’ their beloved pastor in their hearts as Saint Romero of the Americas.

It is the greatest grace and privilege of my life to have known and worked with Archbishop Romero and to have enjoyed his friendship. There are times in life when one catches a fleeting glimpse of God at work in the world and Christ’s presence amongst us. The man we all knew as ‘Monseñor’ provided such a glimpse for me.

I was awakened at 5am on the morning of Tuesday 25 March 1980 by a telephone call from the Jesuit Provincial’s office in San Salvador with the devastating news that Archbishop Romero had been assassinated the previous evening. He was shot just above the heart with a single exploding bullet fired by a death squad marksman acting, according to El Salvador’s current President Funes, ‘with the protection, collaboration or participation of state agents’. He had just completed his homily and was moving to offer the bread and wine at the Mass he was celebrating in the chapel of the hospital where he lived. He fell at the foot of a huge crucifix with blood streaming from his mouth, nostrils and ears. A nun on the front bench recorded the Mass and it is a jolting shock now to listen to the sound of that shot, the moment of martyrdom of the Archbishop of San Salvador.

Oscar Romero was an unlikely martyr. A devout boy of humble origins, he entered junior seminary aged 13, completed his studies in Rome and was ordained there in 1942. Then followed 25 years of exemplary priestly service in San Miguel where he became Chancellor of the Diocese, Cathedral Administrator, Guardian of the Shrine of Our Lady Queen of Peace and editor of the diocesan newspaper. He was renowned as a fine preacher, close to the people and sensitive to the needs of the poor. He had a genuine simplicity of lifestyle and, it seems, a quick temper for the transgressions of his fellow clergy. He was a man of prayer; he wore the scapular and was devoted to the rosary. He was a pastoral priest, loyal and orthodox, the very best of his vintage.

After this came seven years of pastoral famine: Romero moved to San Salvador to become Secretary of the Bishops’ Conference and later Auxiliary Bishop. As an ecclesiastical bureaucrat he was like a fish out of water and seemed to undergo a kind of mid-life crisis. He reacted strongly against many of the new pastoral directions and initiatives that emerged from the Latin American bishops’ landmark meeting at Medellín, Colombia, in 1968. By his actions, his words and his silences, he was seen to be stubbornly at odds with the social commitment of the clergy and basic Christian communities of the archdiocese, who were responding to the exploitation, suffering and hunger in the countryside through education and organisation in the rural parishes. His reputation as a highly conservative prelate stems from this period.

He was then moved out of the limelight for three years when he was appointed bishop of a rural diocese. He was back serving the poor communities, and he came to realise that the repression and exploitation he had seemed to overlook in San Salvador was a shocking reality. We could say that the scales fell from his eyes. ‘I began to see things differently,’ he said. He reverted to the pastoral sensitivity of earlier years but with newly-digested experience and fresh discernment.

In February 1977, against all the odds and to the consternation of the clergy, he was named as Archbishop of San Salvador. But this delighted the military and the coffee barons who wanted the Church back in the sacristy and an end to the social and pastoral projects which gave heart and encouragement to the landless poor. But the shy, retiring, conservative Romero, the man they thought would cause no waves, had changed and allowed himself to be changed.

Romero’s installation as archbishop coincided with a massive presidential electoral fraud, followed by killings and unprecedented national tension. Three weeks later a Jesuit priest, Rutilio Grande, was murdered by a death squad as he drove to say Mass in an outlying village. His body was riddled with bullets – police bullets. Romero’s initial disbelief turned into prophetic determination.

He suspended all formal relations with the government until the assassins would be brought to justice. He opened a diocesan legal aid centre to document all the killings and disappearances and to give support to the families and communities affected. But crucially, on the Sunday following Grande’s death, Romero decreed that the churches of the diocese be closed and all the Masses cancelled. He called the faithful to attend a single Mass which he celebrated in front of the cathedral. He preached eloquently about Fr Rutilio to a crowd of over 100,000 – a passionate witness to the ugly truth.

The wealthy Catholics from the land-owning and commercial class were seething at the betrayal they felt. For his part, Romero visited dozens of different communities and parishes and heard the experiences, the fears and the hopes of the people. They queued up to see him in his office and he listened until late into the night. Repression intensified and was documented; so too the kidnappings and church occupations organised on the left.

Romero’s theology is best-described as the theology of the beatitudes. Romero contended that only if we put the beatitudes into practice can we begin to build that civilisation of love to which we all aspire.

A civilisation of love is not sentimentality, it is justice and truth. A civilisation of love that did not demand justice for people would not be true civilisation….. it is only a caricature of love when we try to patch up with charity what is owed in justice, when we cover with an appearance of benevolence what we are failing in social justice. True love means demanding what is just. [1]

Romero’s own space was his cathedral. With the media closed to him, it was from his pulpit at Sunday Mass, week in, week out, that he spoke the truth and denounced clearly and unambiguously the evil that was taking place.

Over his three years as archbishop, Romero had to confront a plethora of colossal challenges. He faced and sought to respond to pervasive and extreme poverty; to paramilitary killings of community leaders; to peasant massacres and the indiscriminate shooting of urban demonstrators by the security forces; to the torture and disappearance of political prisoners; to the decapitation and mutilation of death squad victims; to the assassination of six of his priests and dozens of catechists; to the deportation of foreign clergy; to the desecration of churches and their tabernacles; to the public threat to exterminate all the Jesuits in the country; to the bombings of the diocesan radio station and printing press; to the discovery of a suitcase of dynamite placed behind the altar at his Sunday Mass; to the suspension of habeas corpus and fundamental constitutional guarantees; to a military-civilian junta installed by military coup; to the kidnapping and execution by armed leftist groups of local and foreign businessmen and government ministers; to the occupations of churches, embassies and government ministries by popular movements; to continuous campaigns of slander and defamation in the press; and to death threats from both the right and the left.

He preached and he spoke out, trying always to find the words to convey the horror of what was happening in a deeply Catholic country which, he said, had come to resemble the dominion of hell.

As El Salvador edged towards war, the threats and insults became intense; Romero knew he was going to die. Those around him tried to persuade him to wear a bullet-proof vest. His response was simple: ‘Why should the shepherd have protection when his sheep are still prey to wolves?’

In his homily the day before he died, he tackled the most difficult question that was being put to him insistently: how should the ordinary soldiers respond when put under orders to kill and massacre? This was his conclusion:

Before an order to kill that a man may give, God’s law must prevail: Thou shalt not kill! No soldier is obliged to obey an order against the law of God….It is time to obey your consciences rather than the orders of sin.... I beg you, I beseech you, I order you in the name of God: Stop the repression! [2]

Archbishop Romero had pronounced his own death sentence, and he knew it. The military high command read it as incitement to mutiny and their plan for Romero’s murder was activated. And the good shepherd died for his sheep.

He had written in the notes of his last retreat: ‘My disposition should be to offer my life to God, whatever way it may end. He helped the martyrs and, if need be, I will feel Him very near as I make my last breath.’

In the end Romero’s life was not snatched away; rather, like Jesus, he freely gave his life for his people. We could say he died ‘eucharistically’ in the eucharist.

Across the globe Oscar Romero is embraced today with admiration, with affection and with pride as an icon of holiness, a model of a bishop and a credible witness to the gospel of Jesus Christ for these sceptical times. A deeply spiritual man with a rich prayer life, his example to us is the beautiful and seamless synthesis he made in living and witnessing to faith and promoting peace with justice. He was utterly orthodox and utterly radical. He has shown that ‘the preferential option for the poor’ is not just a glib phrase. He lived it out and finally offered his life for the poor.

Santo subito!

Julian Filochowski is Chair of the Archbishop Romero Trust.

For a fuller discussion of Archbishop Romero’s ministry and martyrdom by Julian Filochowski visit the Trust’s website here.

[1] Homily of Archbishop Oscar Romero, 12 April 1979.

[2] Homily, 23 March 1980.

Articles about Archbishop Oscar Romero on Thinking Faith:

![]() ‘Telling Romero?s Story’ by Jan Graffius.

‘Telling Romero?s Story’ by Jan Graffius.![]() ‘Romero: the voice of those who had no voice’ by Michael Campbell-Johnston SJ.

‘Romero: the voice of those who had no voice’ by Michael Campbell-Johnston SJ. ![]() ‘The Continuing Presence of Archbishop Romero’ by Rodolfo Cardenal SJ.

‘The Continuing Presence of Archbishop Romero’ by Rodolfo Cardenal SJ. ![]() ‘Oscar Romero: the people?s saint’ by Rt Rev Maurice Taylor.

‘Oscar Romero: the people?s saint’ by Rt Rev Maurice Taylor.

![]() ‘Another beatification?’ by Michael Campbell-Johnston SJ.

‘Another beatification?’ by Michael Campbell-Johnston SJ.