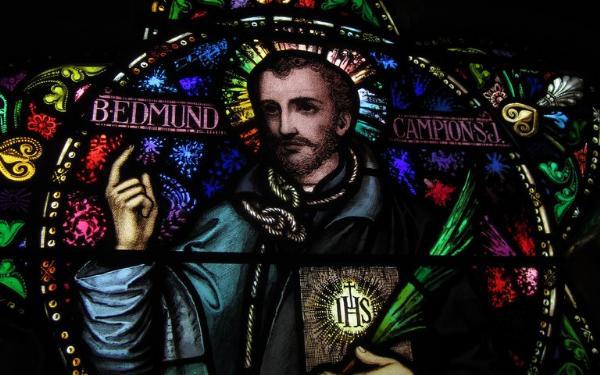

On 1 December, the Society of Jesus celebrates the Feast of Jesuit martyr, St Edmund Campion and companions. Campion scholar, Gerard Kilroy recounts the final days and hours of Campion’s life, and looks at how their events reveal different aspects of his character: the friend; the scholar; the saint and martyr. Which of these descriptions best represents the patron of the British Province?

Edmund Campion was hanged (he was spared the pain of disembowelling while alive by the intervention at Tyburn of Lord Charles Howard) on 1 December 1581. Within six weeks, the English Ambassador in Paris, Sir Henry Cobham, was writing to Sir Francis Walsingham, Secretary to the Privy Council.

I sent you a small book on the death of Campion. They have been crying these books in the streets with outcries naming them to be cruelties used by the Queen of England.

L’Histoire de la Mort que le R. P. Edmund Campion may have been small, but it caused a big stir in Paris; in London, many accounts, in prose and verse, of his trial and martyrdom were already circulating in manuscript, and were in print by February 1582. Scribes such as Stephen Vallenger, who had written accounts of Campion’s four disputations in the Tower of London, or printers like Blessed William Carter, who had paid men to copy accounts by hand, were captured, tortured and (in Vallenger’s case) mutilated. The Recorder of London, William Fleetwood, seized the printing press where the first English account, A true reporte of the death and martyrdome, was printed. Richard Verstegan, the printer, escaped to Paris, and immediately turned to producing broadsheets and engravings of the martyrdom. By 1584, his engravings were circulating (sometimes improved by Italian engravers like Cavalieri) all over Europe, and the Queen and her Privy Council were forced to defend themselves against a veritable tide of hostileprint from Wilno to Rome. Two of the best prose writers in English, Robert Persons and William Allen, both personally attached to Campion, launched book after book setting out the injustices of a benighted country and attached Verstegan’s engravings to their writings. Meanwhile poems, like Henry Walpole’s ‘Why do I use my paper, ynke and penne?’, circulated secretly among courtiers, lawyers and gentry; William Byrd set this poem to music, and settings for lute and voice survive.

The Elizabethan regime may have dismembered Campion’s body, but the battle over his reputation was as fierce as the battle over the body of Patroclus in the Iliad. The topic was still contentious in 1587 when the censors, in the week before the execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, took out 47 lines asserting that Campion died for religion from the work we know as ‘Holinshed’, the ‘Continuation’ of the Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

What was lost in all this noise was Edmundus Campianus Anglus Londinensis, the boy born in the heart of the printing trade, Paul’s Churchyard, son of an anti-Catholic publisher also called Edmund, schoolboy prodigy at St Paul’s (1547-52) and Christ’s Hospital (1552-57), who was chosen to address the new queen, Mary Tudor. Also lost was Edmundus Campianus Oxoniensis, the brilliant Oxford scholar (1557-70) who could turn a speech on the earth and moon into a subtle plea to the Queen and the Earl of Leicester not to interfere in the university’s affairs; and the carefree, companionable novice in Brno (1573-74) and lecturer in rhetoric in Prague (1574-80), whose drafts for student performances on feast days like Corpus Christi or All Souls survive in autograph at Stonyhurst. And, of course, Edmund Campion, the affectionate friend who effortlessly attracted patrons and friends among merchants, aldermen, nobles and foreign princes.

Descriptions of Campion as a friend seem to deal only in superlatives. Letters to Campion from the translator of the Rheims New Testament, Gregory Martin, begin ‘Dilectissime’ (‘most dearly beloved’) or ‘Suavissime et optime’ (‘sweetest and best’). Robert Persons, Campion’s superior on the mission to England, describes himas ‘facillimi ingenii’ (‘of a most yielding disposition’), a trait that was, literally, to be the death of him. [1] In fact, all four of the major decisions that led to his capture and subsequent torture were decisions made on the point of, or after, departure, and in response to requests from others.

The first of these occurred as he was leaving Hoxton, at the end of the first conference of the mission. Campion was asked by Thomas Pounde, a cousin of the Earl of Southampton, and other leading Catholics, to write a testament to be used as evidence of the spiritual intentions of the mission, in case he was captured or killed. Campion, ‘a man of a singular good nature’ (says Persons), agreed quickly:

he arose from the company with whome he was & taking a penne in his hand wrote presently upon the end of a table that stood by in lesse I suppose then half an houre this declaration following.[2]

‘This declaration following’, which we now know as Campion’s ‘Brag’

, was penned purely as a last testament, but within days, ‘wonderfull many copies were taken thereof in a small time’. Not surprisingly, the ‘Brag’, circulating widely, made Campion public enemy number one: it is one of the finest pieces of prose from this period.

The second liminal decision was when he was leaving the next conference at Uxbridge. The principal Catholics present asked Campion to write something in Latin (the language of academic discourse) addressed to the two universities. Campion agreed and, after listening to all their proposals, said he would write something on the despair of heresy: this was the start of Campion’s Rationes Decem (‘Ten Reasons’).[3] According to Persons’ handwritten notes, it was only when he was leaving that Campion casually suggested that they acquire a printing press. These two decisions provoked one of the biggest manhunts in Elizabethan history, but neither Campion’s ‘Challenge’ nor the printing press was a carefully considered decision.

The next decision brings us very close to Campion the man. Campion, Persons, Stephen Brinkley the printer and a team of Marian priests who had helped in the printing of the Rationes Decem in the attic at Stonor Park in Henley, were enjoying a brief moment of triumph after Fr William Hartley had distributed the books at the University of Oxford Act in St Mary’s on 27 June 1581. Hartley revealed that the bookbinder servant of Roland Jenks, a famous recusant publisher in Oxford, had threatened his master with exposure of his secret London bookbinding house.[4] Persons’ face changed colour, and he immediately had two horses saddled to see if they could get to the house in Bridewell before the pursuivants, as it was full of his books and sacred objects. It was too late, and the servants brought back the melancholy news that Persons’ Oxford pupil, Alexander Bryant, had also been captured. When news of Bryant’s dreadful tortures – he was starved, racked and had pins inserted beneath his fingernails – first reached them, Persons and Campion spent two anxious days and sleepless nights in prayer and discussion of how they would act if captured. They decided it was too dangerous to stay at Stonor and Persons resolved that the safest place for Campion to go was Norfolk. Campion, under obedience to Persons, agreed, but asked permission to travel via Lancashire to pick up his books at Park Hall, the home of the politician, Richard Hoghton. They set out from Stonor on horseback, said tearful farewells, embraced, exchanged hats as a gesture of friendship and set out in different directions. A few minutes later, Persons heard a familiar voice calling his name and turned to find Campion riding to catch him up. Campion had discovered from his lay brother, Ralph Emerson, that their route lay close to Lyford Grange, a mere eight miles outside Oxford. The imprisoned recusant owner, John Yate, had been begging Campion to visit his wife and the Bridgettine nuns living in the house. Persons reluctantly agreed, anxious that Campion would find it difficult to resist pressure to stay longer than was safe.

Campion offered to make Ralph Emerson his temporary superior and promised to stay no more than one night. Campion stuck to his promise and he and Emerson left as agreed after Mass and dinner the next day. By the afternoon, a whole crowd of Oxford scholars had arrived at Lyford Grange: news of Campion’s presence had spread among the tight network of private halls, inns and taverns, safe houses and farms outside the city, that by 1581 made up Catholic Oxford.

Frustrated at missing Campion, the scholars implored Fr Thomas Ford, one of the two priests in the house, to ride after Campion and beg him to come back. Ford (a former fellow of Trinity College) is described by Campion’s first biographer, Paolo Bombino, as ‘Campiano addictissimus’ (most addicted to Campion), so he was easily persuaded to ride hard. He knew where his fellow priest, Fr John Colleton would have taken Campion, and found him in an inn near Oxford, disputing with a large body of academics. Ford pressed his case hard, the scholars all supported him; Campion, close to tears, fell back on his last defence, that Emerson was the superior. The scholars had an answer to this: that if Emerson went to collect his books from Lancashire, Campion could stay two more days and then rejoin Emerson on the way to Norfolk. Emerson yielded and Campion returned to Lyford Grange. It was a fateful and, ultimately, fatal decision, since George Elliot, the alleged murderer and rapist who had offered Walsingham the capture of Jesuits in return for indemnity, arrived at Lyford Grange on the following Sunday morning, accompanied by a Queen’s Messenger with a warrant that gave them power to overrule the local magistrates. In Berkshire and Oxfordshire most of these had strong Catholic sympathies. A powerful drama ensued, in which Justice Fettiplace (whose family were linked many times over to the Yates) and fifty cavalrymen of the trained band of Berkshire tried not to find the priests; it was only as they were leaving, on the second day, that the Queen's Messenger himself asked if panelling on the stairway had been tapped and saw the look of horror on the face of the man appointed to be Elliot’s minder.

Campion the saint and martyr has been the focus, from the earliest accounts of his ‘Death and Martyrdom’ down to Evelyn Waugh’s preface to his 1946 edition of his elegantbut scantily researched Edmund Campion, where he writes:

The hunted, trapped, murdered priest is our contemporary and Campion’s voice sounds to us across the centuries as though he were walking at our elbow.[5]

In an inevitable reaction to this hagiographical tradition, it has become fashionable for historians of the early modern period to see Campion as orchestrating a carefully planned confrontation with the authorities; as acting out a melodrama already conceived in Rome; as a reckless author of his own fate; as an unbearably angelic and impractical orator with unrealistic perception of the likely outcome of the mission. Read in this revisionist way, the ‘Campion affair’ becomes a highly charged piece of carefully staged political drama.

Examination of archival evidence reveals a very different view of the mission of 1580-81. In the first place, one could argue that it is misleading to call it the ‘Jesuit mission’, since it was conceived, planned and directed by Dr William Allen who, in the autumn of 1579 finally persuaded the Jesuit General, Everard Mercurian, to send two of his best men to England. Allen did not tell either Mercurian or Campion that Dr Nicholas Sander, a former Fellow of New College and leading Catholic controversialist, had already sailed for Ireland with a military expedition of six hundred Spanish troops under an Hispano-Papal flag. Persons records the horror with which he and Campion heard the news from Allen when they reached Rheims in May 1580. Both instantly saw that Sander’s enterprise would lead to his death and be laid at their doorby the authorities in England. Whereas Allen’s letter to Campion in Prague, telling him the good news that Mercurian had agreed to lend him to the mission, had begun, ‘Mi pater, frater, fili, Edmunde Campiane’ (‘My father, brother, son, Edmund Campion’), Campion’s interview with Allen in Rheims is distinctly frosty, if not plain indignant:

Well Sir heer now I am: you haue desired my going to England and I am come a long iourny as you see from Praga to Rome and from Rome and do you think my labors in England may countervail all this travail as also my absence from Boemia, where though I did not much, yet I was not idle nor unemployed, and that also against hereticks.[6]

There is much to suggest that Campion was reluctant to leave Prague and come to England. As Thomas McCoog SJ has suggested, there is a long time between Allen’s letter in December and Campion’s actual departure sometime in March. Secondly, Campion agreed to come only on condition he was not in charge. Thirdly, he asked twice, once in 1573 and again in 1580, for a mitigation of the obligations imposed on Catholics by the Papal bull, Regnans in Excelsis. At his trial, Campion expresses strong doubts as to the legitimacy of the Papal bull, and carefully distinguishes between the pope's authority in spiritual and temporal matters. Whereas Allen, born in Lancashire, and Persons, from deepest Somerset, both thought England could be re-converted easily to Catholicism, Campion, a Londoner, seems to have been sceptical. In 1573, Campion left Douai, where Allen’s dual aims for both political and spiritual enterprises were already evolving, to go to Rome, where he joined the Jesuits who, at that stage, had no mission in England. One wonders whether a boyhood in Paul’s churchyard, in the heart of the conflicted sphere of print and pulpit, within sight, sound and smell of Smithfield’s horrendous burnings, had led him to fear the worst kind of muddle: a dangerous confusion of spiritual and political objectives.

Campion was not a reckless agitator, but he knew and had reckoned the expense. When asked why he was wearing such a rough coat for the journey, he replied that any clothes were good enough for a man going to be hanged. From Rheims onwards he must have known how his life would end and, while obviously anxious about his response to the rack, he behaved with all the dignity of a man free of the fear of death itself. Far from being a planned rush to martyrdom, Campion’s path was a series of impulsive and generous responses to the extraordinary affection he inspired wherever he went. The contemporary historian, William Camden, who was given access to the state papers by Lord Burghley, said that Queen Elizabeth regarded ‘most of these wretched little priests’ (misellis his sacerdotibus) as not guilty, but she did blame their ‘superiores’, to whom they were bound in obedience. Four hundred years later, it is hard to disagree with Camden's balanced verdict.

The evidence of his letters to his fellow-novices in Brno, of Martin’s letters to Campion and of Persons to his companionsuggest that, when given the chance, Campion's natural instinct was for academic life and debate. His letters reveal a man blissfully happy leading a collegiate academic life whether in Brno, Prague or Oxford. Campion’s most recurring topic in the letters is a request for the return of borrowed or missing manuscripts. His last free journey was made to retrieve his books. He was a scholar steeped in a tradition of European scholars who effortlessly moved between Prague, Rome and Oxford. It is significant that Campion’s famous scaffold quotation from St Paul, ‘Spectaculum facti sumus Deo, angelis, hominibus’ (‘We have been made a spectacle to God, angels and men’) is in the passive voice. Campion was thrust onto this very public and political stage; everything indicates that he would have been happier to continue debating in a tavern near Oxford.

Campion was not just a martyr who happened to have been a scholar; he was captured, surrounded by other Oxford scholars, in what was, in effect, a private hall of the University of Oxford; he remained Edmundus Campianus Oxoniensis until his last, Latin prayer on the scaffold.

Gerard Kilroy, Honorary Visiting Professor at University College London, studied the way Edmund Campion's memory was preserved in manuscript and stone in Edmund Campion: Memory and Transcription (Ashgate, 2005). His most recent book is an edition of The Epigrams of Sir John Harington (Ashgate, 2009), where Harington uses wit to conceal his profound religious ideas in a complex scheme of poems based on the Rosary. He has recently published on Harington's covert transcription of subversive manuscripts by Campion and Robert Persons SJ, and on the emblematic buildings of Sir Thomas Tresham. He is now working on a new biography, Edmund Campion: A Scholarly Life, to be published by Ashgate in 2014.

[1] Robert Persons SJ (1546-1610) remains the main source of biographical material on Campion. Born in Nether Stowey, Somerset, the son of a formidable mother who lived till she was 92, he became a Fellow of Balliol College and first encountered Campion in Oxford.Persons left England in 1575, joined the Jesuits and worked with Dr William Allen to secure Jesuit participation in the English mission. Because Campion, who was six years his senior, refused to take charge of the mission, Persons was the superior. Persons escaped to France in 1581, where he put to good use his formidable skills as a controversial and devotional writer. He began to write a biography of Campion, but left only his Notae breves for the later chapters. Paolo Bombino, author of the first full biography (published in 1618 and in a better edition in 1620) took much of his material from Persons’ oral accounts. Persons is a master of biographical detail, especially in the unpublished notes, copied by Fr Christopher Grene in 1689, but his memory of dates is sometimes inaccurate, and he says little about Campion's early life. (For more information on Persons, see http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20100414_1.htm)

[2] Archivum Britannicum Societatis Iesu (ABSI), Collectanea, A.I-IV, fol. 136v.

[3] De haeresi desperata: a theme that dominates the opening of the Rationes Decem.

[4] Roland Jenks had gained notoriety on 4 July 1577 because a plague carried off the entire court - judge, clerk, lord lieutenant, sheriff, coroner and over three hundred other people - at the Oxford Assizes where he was condemned to lose his ears for printing Catholic books. This was widely interpreted as a divine judgement, and the trial became known as the ‘Black Assizes’. The event is described on the first page of ‘The Continuation of the Chronicles of Holinshed’ (1587).

[5] This is the reading in the Preface to the second (American) edition (Boston: Little, Brown, 1946); the English second edition, published in 1947 by Hollis and Carter, has 'haunted' (p. viij), which appears to be a typographical error.

[6] ABSI, Collectanea, A.I-IV, fol. 114r.

Listen to Fr Billy Hewett reading an abridged version of Campion’s Bragge: