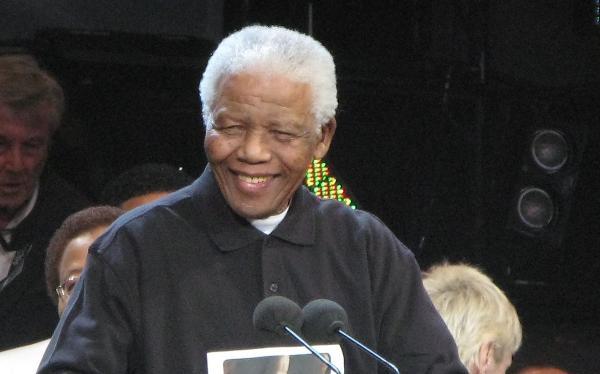

As Nelson Mandela celebrates his 90th birthday, Gilbert Mardai SJ pays tribute to this ‘apostle of justice’ whose example of courage, forgiveness and patience on his ‘long walk to freedom’ are an inspiration to Christians and to all who yearn for a fairer and more human world.

On 18 July 1918, Africa and the world were blessed with the birth of Rolihlahla in a tiny village on the banks of the Mbashe River in province of Transkei. The name Rolihlahla in Xhosa means ‘pulling the branch of a tree’, but its colloquial meaning more accurately would be ‘troublemaker’. Didn’t Shakespeare write, ‘What’s in a name?’ And how true this was for Rolihlahla! To the apartheid regime of South Africa in the 1950s and early 1960s, Rolihlahla was indeed a troublemaker. So much was the ‘trouble’ he made for justice that at the mere mentioning of his name conflicting emotions churned inside people like President P.W. Botha. To silence him, he was arrested and put in jail. This measure had little or no effect because the world spoke out against apartheid and for the freedom of this man and his fellow prisoners.

Who would have thought that Rolihlahla was going to be the person so well known today by young and old alike, rich and poor, oppressed and free, sick and healthy? Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela – what an extraordinary human being! The whole world is celebrating the life of a man who has given all his life – 90 years – to fight for justice. He should be called the apostle of justice. For the cause of justice he was ready to die rather than turn a blind eye to the atrocities committed by the apartheid regime in South Africa. He was imprisoned on Robben Island for twenty-seven and a half years. Instead of seeing these years as a time when all his hopes were shattered for ever, he saw them as his ‘long walk to freedom’.

Mandela’s name in Robben Island was 46664 – the 466th prisoner in 1964. But the world did not reduce his identity to a mere number; he was Mandela, Nelson Mandela. We celebrate, this year, the 90th birthday of an extraordinary man, an apostle of justice. Who would have wanted to spend more time in a prison such as Robben Island after twenty-seven and a half years? And yet, when F.W. de Klerk announced to Mandela on 9 February 1990 that he was going to release him from prison the following day, Mandela preferred to have a week’s notice. He needed time to notify his people of his release, and he wanted to be released with dignity, not in a rush. He writes, ‘After waiting twenty-seven years, I could certainly wait seven days.’[1] What is more extraordinary is his desire ‘to be able to say good-bye to the guards and warders who had looked after [him] and [he] asked that they and their families wait for [him] at the front gate, where [he] would be able to thank them individually.’[2] He wanted to thank the guards and warders! Indeed, ten thousand days in prison formed an apostle of justice, for with justice there is respect, total respect, for the dignity of all human beings.

A new life was just beginning. As soon as he walked out of the gates, he was met by a roaring crowd. Mandela writes,

When I was among the crowd I raised my right fist, and there was a roar. I had not been able to do that for twenty-seven years and it gave me a surge of strength and joy. We stayed among the crowd for only a few minutes before jumping back into the car for the drive to Cape Town. Although I was pleased to have such a reception, I was greatly vexed by the fact that I did not have a chance to say good bye to the prison staff. As I finally walked through those gates to enter a car on the other side, I felt – even at the age of seventy-one – that my life was beginning anew. My ten thousand days of imprisonment were at last over.[3]

The first words that Mandela spoke to the people at the rally at the Grand Parade in Cape Town marked the beginning of a life of a free apostle of justice dedicating his life for the freedom for all. He said,

Friends, comrades and fellow South Africans. I greet you all in the name of peace, democracy and freedom for all! I stand here before you not as a prophet but as a humble servant of you, the people. Your tireless and heroic sacrifices have made it possible for me to be here today. I therefore place the remaining years of my life in your hands.[4]

These words were spoken in 1990, two years after the Free Nelson Mandela concert held in London. He said he was placing the remaining years of his life in the hands of his friends, comrades and fellow South Africans. By these words Mandela committed himself to making his own the problems and the struggles of his people, the victims of the oppressive apartheid regime. Eighteen years have passed since he uttered those words. Four of those years were spent in the campaign for freedom from apartheid. Five years were spent in the office of President, bearing the responsibility for leading a newly-born democratic nation. In 2008, Nelson Mandela is back in London having spent nine years as an ordinary citizen of South Africa, but dedicated to the fight against HIV/AIDS through the 46664 campaign. Yet he does not want to be seen as a prophet; nor does he want to be seen as a messiah. Mandela sees himself as ‘an ordinary man who had become a leader because of extraordinary circumstances.’[5]

In such extraordinary circumstances an apostle of justice has come into our midst. Committed to justice and freedom for all, he dedicated his whole life to this noble cause. In words strongly reminiscent of the Apostle Paul’s ‘I have run the race’, in the evening of his life, to Timothy (2 Timothy 4:6-8), Mandela writes,

I have walked that long road to freedom. I have tried not to falter; I have made missteps along the way. But I have discovered the secret that after climbing a great hill, one only finds that there are many more hills to climb. I have taken a moment here to rest, to steal a view of the glorious vista that surrounds me, to look back on the distance I have come. But I can rest only for a moment, for with freedom come responsibilities, and I dare not linger, for my long walk is not yet ended.[6]

Mandela may not have been at the evening of his life then. But he had ‘walked that long road to freedom’ up to a point. Like Moses, he was able to climb up the hill top and look back on the distance covered and realise what more is still left to cover. Unlike Moses, he did not die; he continued walking towards the ‘Promised Land’. London hosted a concert in Hyde Park on 27 June this year to wish Mandela a Happy 90th Birthday. It was a bash! Looking frail, but still walking and determined to give a smile to all those who were gathered in the park and those watching all around the world, Mandela waved his hand to greet the people and paused to give a message. This time it was a message of a man in the evening of his life, and a message that will reverberate through the entire world for many years to come. This is what he said,

Friends, twenty years ago London hosted a historic concert which called for our freedom. Your voices carried across the water and inspired us in our prison cells far away. Tonight we can stand before you free. We are honoured to be back in London for this wonderful occasion [and] celebration. But even as we celebrate, let us remind ourselves that our work is far from complete. Where there is poverty and sickness, including AIDS, where human beings are oppressed, there is more work to be done. Our work is for freedom for all. [Friends], and all those watching all around the world, please continue supporting our 46664 campaign. We say tonight after nearly 90 years of life, it is time for new hands to lift up the burdens. It is in your hands now. I thank you.

With these words, the great apostle of justice, ‘a humble servant’, bade farewell to the public arena a free man, this time not raising a fist but waving a hand. When he walked out of Robben Island he told the people gathered in Cape Town, ‘I therefore place the remaining years of my life in your hands.’ With those words he entered the public arena a free man and, at seventy-two years of age, a very strong man indeed. Since the work is far from complete he now places it in our hands – ‘it is in your hands now’. With these words he confirms the right of the poor, the sick and the oppressed to take their future into their hands and our duty to give witness to justice by first being just ourselves. Time has come to change the course of history. It seems fitting to recall the words of Ignacio Ellacuría, a Jesuit liberation theologian martyred in 1989 by the Salvadoran military because of his outspoken criticism of the injustices in El Salvador. He gave this speech on 6 November 1989 and it turns out that this was the last speech he ever made:

Together with all the poor and oppressed people in the world, we need utopian hope to encourage us to believe we can change its course, but subvert it and set it going in another direction […] On another occasion I talked about a “coprohistorical analysis”, that is, the examination of our civilisation’s faeces. This examination seems to show that our civilisation is very sick. To escape from such a dire prognosis, we must try to change it from within.[7]

Ellacuría spoke these words nearly twenty years ago, but little has changed in the world today. What he had in mind were evils such as ‘poverty, worsening exploitation, the scandalous gap between rich and poor, ecological destruction, as well as the perversion of actual advances in democracy and the ideological manipulation of human rights.’[8] If these evils are not overcome, it is difficult to see how the world today can escape from Ellacuría’s dire prognosis. It is not surprising therefore that Mandela tells us that ‘there is more work to be done’. This work cannot be done in silence. In a world where violence and crime are becoming increasingly rampant it is the responsibility of everyone to speak out against a life that leads to dehumanisation, but more importantly it is the responsibility of everyone to examine our lifestyle and choose carefully the kind of values we want to promote.

So far this year, 21 teenagers have been violently killed on the streets of London. When the 16-year-old Jimmy Mizen was stabbed to death at a baker’s shop in Lee, south-east London, on 10 May 2008, everyone started asking questions: What is going on? What has gone wrong with our society? Jimmy’s father said,

People are saying something must be done. I just wonder how futile it is, with more and more legislation and laws. Perhaps we all need to look to ourselves and look to the values we would like and our responses to situations in our life. Sometimes we might be drawn into certain ways of living. It is our choice, but change has got to come from all of us. Look out for each other and take care of each other and look to the sort of values we need to live with.[9]

Indeed the choice is ours and change must come from all of us. And, as the Jesuit Provincial, Fr Michael Holman wrote recently, ‘we can ban knives, increase penalties and purchase metal detectors, but they are superficial solutions to a deeper malaise that in many ways our society is reluctant to address.’[10] A deeper malaise indeed: if London is not enough, think of Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Darfur, Zimbabwe, and the list goes on – the disturbing evidence of a dehumanised world.

By the example of his life, total dedication and commitment for the cause of justice, Mandela has shown us all what it means to make a difference in the world. If Mandela made so much trouble to bring about change in South Africa, then trouble is worth making. Our world today needs as many ‘troublemakers’ as possible – men and women, motivated by the same dedication and commitment as Rolihlahla – to start making a difference. Of course, this is easier said than done, but the concerts and parties held in honour of this great apostle of justice will mean nothing if no concrete action is taken to actualise the promises made on stage. In ten years’ time Mandela will be a hundred years old. I really hope that he will still be alive. In 2018 we should be able to have concerts, not only in Hyde Park, but in many other places the world over, to celebrate Mandela’s life and to be able to tell him that the world has changed; it has become a better place now, not only because of him, but because of what we have been able to do thanks to his inspirational example. As we salute Mandela on his birthday this year, we take it in our hands the work of making this world a better place to live in – a world of ‘humane humanity’[11] where joy, creativity, patience, art and culture, hope, solidarity, and, above all, love, are the values we live with. It is in our hands now to seek the way that leads to peace, to ensure that human rights, human dignity and freedom for all are everywhere respected, and that the world’s resources are generously shared. It is in our hands now to change the world.

Gilbert Mardai SJ is a Jesuit priest from Tanzania, currently living and studying in London.

[1] Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom (London: Abacus, 1995), p. 667.

[2] Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, p. 672.

[3] Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, p. 673.

[4] Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, p. 676.

[5] Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, p. 676.

[6] Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, p. 751.

[7] Quoted in Jon Sobrino, The Eye of the Needle (London: Darton, Longman and Todd Ltd., 2008), p. 17.

[8] Sobrino, The Eye of the Needle, p. 18.

[9] Quoted in Michael Holman SJ, ‘Our Lost Children’, in The Tablet, 28 June 2008, p. 7.

[10] Holman, ‘Our Lost Children’, in The Tablet, 28 June 2008, p. 7.

[11] I borrow this expression from Sobrino, The Eye of the Needle, p. 46.