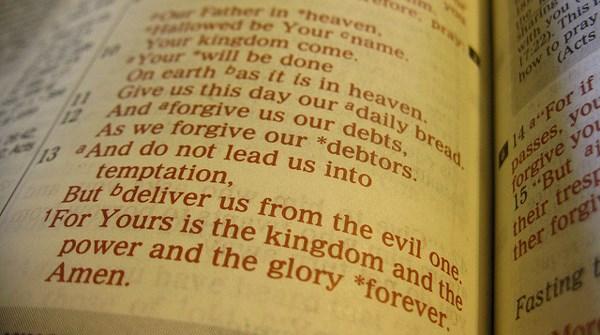

In the gospel reading for Thursday 21 June, which is taken from the Sermon on the Mount in Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus teaches his disciples how to pray the Lord’s Prayer. Familiar as the words of the Our Father may be, how often do we reflect on their meaning? Joseph Munitiz SJ encourages us to do so by considering the task of translation.

The best-known prayer, used by Christians everywhere, is a translated text: we no longer have, if it was ever in common use, the version spoken by Jesus Christ in Aramaic or Hebrew. Our earliest version is in Greek, and that version presents a series of problems to any translator.[i]

A distinction is needed here between a translation and an exegesis (explanation): the translator’s task is (roughly) to express in the words of one language what the words of another language are saying, though clearly excessive literalness may not achieve this. But in some cases the meaning of those words in the target language may not be clear. A good example are the words ‘in heaven’ that follow the address to God the Father in the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:9-13). Strictly, the Greek here says ‘in the heavens’ (plural), and the recent translation of David Bentley Hart respects this. But the problem remains. The meaning here is not obvious: people in the first century were working with a notion of ‘heaven’ very different from that common today. The translator may feel that to convey what Christ meant here it would be better to write ‘in the universe’, but that would be to go beyond the task of the translator into that of the exegete. Similar problems arise with regard to many of the terms found in the prayer: ‘name’, ‘kingdom’, ‘will’, etc.

If the translator simply tries to be faithful to the Greek words, the major problem is with the word epiousion (standardly translated as ‘daily’), which is a hapax, or at least a word rarely found in other Greek texts. Etymologically it is related to the notion of what is coming. But Liddell & Scott in the standard Greek-English dictionary explain this to mean ‘and so current day’. The Greek fathers, conveniently listed and quoted in the great patristic dictionary edited by G.W.H. Lampe, are divided: some, notably Origen, think it pertains fully to the future (‘of the world to come’), but others, among them Gregory of Nyssa, opt for today (‘daily’). In Modern Greek, the Bible Society translation gives boldly ‘necessary for life’, with a footnote alternative ‘of the new world’, both of which seem to be exegetical in character. Of two modern English versions, one gives ‘for the day ahead’ (Hart) and the other ‘for the coming day’ (Nicholas King).

But there are two further points where doubts arise: Pope Francis has drawn attention to the first when he suggests abandoning ‘Lead us not into temptation’ as being false both to the Greek and to the notion of a kindly God. Hart supports him and offers, ‘And do not bring us to trial’, which corrects the Latin, et ne nos inducas in tentationem, and is faithful to the Greek. But the final words, tou ponérou, are also worth attention: ‘from the Evil One’, suggests King, which is probably correct given the role of the Evil One in the Gospel of Matthew (5:37; 13:19,38); Hart gives a less ‘diabolical’ version, ‘from him who is wicked’ – so anyone who might do us harm.

Of course, when we pray a much-loved prayer few people pay much attention to the nicety of the words: cor ad cor loquitur, ‘heart speaks to heart’, as Newman reminded us. However, we are people with minds and it is good to reflect occasionally.

Joseph Munitiz SJ is a writer, and has recently edited and translated Ignatian Spirituality: A Selection of Continental Studies in Translation (Way Books, 2016).

[i] Notable recent translations: Nicholas King, The New Testament (Kevin Mayhew, 2004); David Bentley Hart, The New Testament: A Translation (Yale University Press, 2017). The translation into Modern Greek, very different from New Testament Greek, was published by the United Bible Societies, Athens 1985.