October 2019 is the 400th anniversary of the death of Thomas Stephens SJ, a translator and writer who authored several works including the Kristapurana for which he is best known. This powerful text is much more than an imaginative retelling of the biblical narrative, says Michael Barnes SJ, who celebrates Stephens’ pastoral and literary gifts.

Fr Thomas Stephens SJ, the 400th anniversary of whose death is celebrated this year, was a remarkable linguist and translator, pastoral priest and accomplished poet. A recent journal article refers to him as the ‘Shakespeare of India’.[i] An unlikely comparison – but not entirely fanciful.

Stephens did not set out to be a poet. His first work was a grammar (in Portuguese) of the Konkani language, his second a treatise on Christian faith, written in Konkani. Towards the end of his life he published an epic version of the Old and New Testaments in Marathi, the Kristapurana.[ii] This is the work for which he is famous. His poetry may not be in the same class as Shakespeare or Robert Southwell, but today he is known in Maharashtra as the father of Maratha Christian literature.

From Wiltshire to India

No mean achievement for a country boy from middle England. Let’s begin in the tiny hamlet of Bushton, just south of what is now Royal Wootton Bassett in north Wiltshire, where Stephens was born in 1549, the second son of Thomas and Jane Stephens. Thomas senior was a successful merchant who held the lease of Bushton Manor. There isn’t a church in the village. The nearest is about a mile away, in the village of Clyffe Pypard, half way up the Ridgeway escarpment which commands magnificent views of the bare, gently undulating countryside. Possibly Stephens was baptised here – though it’s more likely to have been in the chapel attached to the Manor.

His elder brother, Richard, studied at Oxford, joined the newly founded seminary at Douai, and worked as professor of theology until his death in 1586. Thomas did his schooling at Winchester, after which he traipsed round the country in the company of a larger than life character called Thomas Pounde, a sometime courtier of Queen Elizabeth, whose main purpose in life seems to have been introducing suitable young men (and himself) to the Society of Jesus.

Pounde and Stephens were much taken by the radical commitment expected of recruits to the new Society as well as by the letters written by far-flung missionaries that were circulating round Europe at the time. They resolved to go to Rome together but, on the eve of their departure, Pounde was betrayed and arrested. Stephens escaped and travelled to Rome alone, where he joined the Society of Jesus along with six other Englishmen, among them the Oxford-educated Henry Garnet, William Weston and Robert Persons.

In 1577, Edmund Campion wrote to Persons from Prague: ‘You are seven; I congratulate you; I wish you were seventy times seven. Considering the goodness of the cause, the number is small.’[iii] Campion was, of course, referring to the needs of the English mission. And given that it was such a priority for English Jesuits at that precise moment it might seem strange that Stephens had other ideas. But his desire to dedicate himself to a very different mission made itself plain early on. Even apart from the powerful attraction of the letters of the likes of Francis Xavier, he would have been well aware that the Formula of the Institute in only its third paragraph speaks about members of the Society being ready to go wherever the Supreme Pontiff sees fit, ‘whether he sends us to the Turks or other infidels, even to the land they call India’.[iv]

By the time he set out from Lisbon on 4 April 1579, the Society had shifted its missionary focus from the radical dispersal which Ignatius originally envisaged to the routine of educational institutions, the work for which the Society soon became famous. Stephens clung to the original ideal, no more taken by the prospect of the settled life of the schoolteacher than he felt committed to resisting persecution back in his native land.

The humanism of a strange new world

He landed in Goa on 24 October 1579 - one of 43 Jesuits to arrive that year. This epic journey with its privations and dangers is vividly described in a long letter to his father. His communications, whether to his family or to members of the Society, reveal something of his character. He comes across as keenly observant, blessed with an enquiring mind and a natural curiosity, thoughtful and clear-sighted in his judgements, yet also fascinated by the strange and unexpected.

He is, for instance, struck by the exotic flora of this new world. The letter to his father finishes: ‘Hitherto I have not seen trees here whose like I have seen in Europe, the vine excepted, which, nevertheless here is to no purpose, so that all the wines are brought out from Portugal.’[v] And his growing interest in language and translation comes through in a letter to his brother Richard, written in late 1583. ‘Many are the languages of these places. Their pronunciation is not disagreeable, and their structure is allied to Greek and Latin. The phrases and constructions are of a wonderful kind.’[vi]

At the Roman College Stephens was schooled both in Thomistic thought and in the humanist values of the Renaissance. What held them together was no theory of intercultural dynamics but a language, Latin, that opened up access to literature of all kinds and, perhaps as significant, modes of using language of all kinds, from syllogistic reasoning to the tropes of classical rhetoric and poetry. Stephens knew that Sanskrit was connected to Marathi and Konkani as Latin was to Italian; the one was the linguistic and cultural key to the other.

The typically Jesuit approach to Christian mission came out of this humanist education. Ignatius expected his Jesuits to be learned, but also to be able to communicate their learning. The two are interdependent, two sides of the one coin, a dialogue that begins with the desire to understand and finds itself rooted in the heart. This was what inspired the likes of Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) who developed an extraordinary dialogue with the Chinese world and Roberto de Nobili (1577-1656) who lived for some fifty years among the Brahmins of Madurai.

The India Stephens encountered was, of course, the centre of Portuguese power. The enclave of Goa was founded as a trading centre by Afonso de Albuquerque in 1510. Within less than a century it was marked by a series of impressive buildings, not least the Bom Jesus, started in 1594 and, after his canonisation in 1622, the place where St Francis Xavier’s body was finally laid to rest. Like all the religious who came to Goa, the Jesuits received a stipend from the Portuguese. Without financial support they could not have operated at all, yet there was always a risk their freedom of movement would be subject to imperial diktat.

The trauma of violence

As an Englishman Stephens was already an outsider in this Portuguese world, and like de Nobili he appears to have experienced a degree of ambivalence towards colonial power and the dilemmas it raised for the missionary. But whereas de Nobili quickly moved outside the area subject to Portuguese control, Stephens spent the rest of his life there. Soon after his ordination he was sent to Rachol, the most important mission-centre in Salcete, some 25 kilometres to the south, and an area of particular concern for the Portuguese in their efforts to establish control of the Goa hinterland.

He responded naturally to Ignatius’s concern that, wherever necessary, Jesuits should learn to address local people in the local vernacular. Yet he also knew that something more was at stake than mere ease of communication. Adapting the Gospel to the local language had the deeper purpose of entering into the spirit of a culture, valuing it as a place where the Spirit was already at work in the world. It took a particularly traumatic event to make him see that the fabric of human culture is always fragile and sometimes needs to be protected from unthinking violence.

The Salcete mission, situated on the very edge of the Portuguese enclave and always subject to internal conflicts and shifting loyalties, was never easy. According to Georg Schurhammer, the Salcete population, scattered over 55 villages, amounted to about 80,000; scores of temples were dedicated to Santery, the cobra-goddess, a form of the fearsome Durga.[vii] In 1560 there were about 100 Christians; by the end of the decade over a thousand. A remarkable growth, but this rapid expansion was achieved in no small measure by force, with the destruction of Hindu temples.

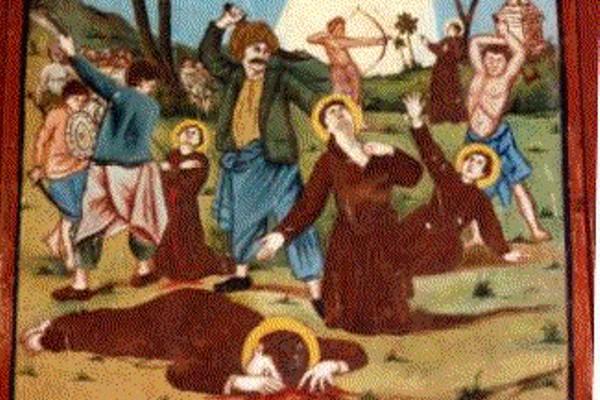

Almost inevitably there was a violent reaction and in 1583 four Jesuits, led by Rudolph Acquaviva, and 48 native Christians were attacked and violently hacked to death at a small outpost called Cuncolim. Today the site of the massacre is covered by an innocuous little chapel. Another chapel, a couple of hundred yards away, covers the ‘well’ – more a damp pit – where the dismembered bodies were dumped. Stephens, recently installed in the ‘college’ or Jesuit community in Rachol, was caught in the aftermath. It fell to him to recover the bodies – one of them a fellow-novice from Roman days – and then go about the painful business of rebuilding the community’s work.

When I visited the spot with a group of Jesuits I was struck by the simplicity of the site. There was no great monument proclaiming what had happened. I did, however, notice a more recent memorial to another massacre set up in a garden on the other side of the dividing wall. It made for sober reading.

This memorial is dedicated to the bravery and valour of the chieftains of Cuncolim who stood against the Portuguese and were treacherously massacred when attending peace talks at the Assolna fort in July 1583.

Some dozen names are listed, a tangible reminder of the ‘other side’ of history. Acquaviva had come to Cuncolim with his companions to mediate in a bitter conflict that had broken out over the desecration of the local temple. Instead they were violently killed – and their deaths led subsequently to a further terrible act of vengeance. The memorial acts as a reminder that it wasn’t just Catholics who suffered violence at that time. Religious difference is never the whole story in inter-communal conflict. The economic and political consequences of disruption of the cultural status quo are often equally significant.

One pertinent comment comes from the Jesuit historian Teutonio de Souza. He criticises recourse to binary thinking, such as the assumption that the ‘pagans’ were implicated in ‘the work of the devil’ while those who supported the missionaries were doing ‘God’s work’.[viii] The truth is always more complex. This was something Stephens came to know through painful experience.

The patience of conversion

However this tragic episode is to be dissected, it was, says Schurhammer, a ‘major disaster’.[ix] By strange chance, two months later came a letter from Stephens’ brother Richard, telling him of the martyrdom of Edmund Campion and his companions at Tyburn. In his reply, written just four years after his arrival in India, 24 October 1583, Stephens gives a graphic description of what happened in Cuncolim. He then passes on a happier story about the strength of faith of a Brahmin boy who was imprisoned by his family yet resisted all attempts to make him give up his Christian faith.

The story is not a pious aside, intended to counter the traumas of Tyburn and Cuncolim. Stephens is touched by the movements of divine providence in the middle of terrible experiences of suffering. The world the brothers share is going through a period of darkness but Thomas consoles himself with an example of patient goodness.[x] The process of conversion takes time and its own form of heroic perseverance; unnecessary pressure leads only to obstinacy – and risks further violence.

Another historian, Ananya Chakravarti, author of an insightful analysis of Stephens’ life and mission, draws attention to his ‘willingness to impute reasonable motivations and sentiments to the people of his adopted land’. His awareness of the seeds of violence built up in him not resentment but a remarkable capacity for empathy, which enabled him to identify with the local culture and its people.[xi]

Pastoral care and catechesis

Stephens spent most of his 40 years on the Indian mission in Salcete. The first half was dedicated to pastoral work, for the ‘salvation of souls’, as Ignatius decreed in the first Formula. He was clearly a wise and sensitive priest. The labour of administration came less easily to him. He was conscious that simply keeping control of the mission would lead to an encounter with the people that was superficial and took little account of his people’s loyalty to their customs and patterns of behaviour.

The Kristapurana was the fruit of long years of prayerful study, preaching and pastoral work. He was aware that brahmin converts were concerned their new-found faith lacked the cultural and liturgical structures they had been so used to. So he began to think in terms of an accompaniment to the catechism, a story to be recited and prayed, raising questions and opening up elucidations of the truth of the Gospel.

Once he had mastered Sanskrit, and produced his grammar of Konkani, Stephens was more and more captivated by the language of the Marathi saints which, according to a modern history, he described as, ‘a jewel among pebbles, like a sapphire among jewels, like the jasmine among blossoms, and the musk among all perfumes, the peacock among birds.’[xii]

He became convinced that no better language could be imagined for communicating the truth of the Gospel. Three editions of the Kristapurana were published, in 1616, 1649 and 1654. A scholarly edition was produced in Mangalore by Joseph Saldanha in 1907 and English speakers are indebted to the more recent translation by Nelson Falcao published in 2012.[xiii] What was Stephens seeking to convey through this great text? And does it have anything to teach a modern audience, some four hundred years later?

Rooting faith in the heart

As a work of catechesis, the not-so-remote model is St Francis Xavier himself – and further back, of course, the convictions of St Ignatius. Xavier learned enough of the local language to produce simple summaries which he repeated to people. More importantly, in the spirit of the Spiritual Exercises, he taught them how to pray. In centring the words of faith round the life of Christ they would come to understand – and relish – its deeper truth. In a letter to the General, from 1601, Stephens writes about ‘the little chapels which Fr Provincial ordered to be erected in remote villages. Here the children can gather to study their catechism and the people can stop to pray when passing by.’[xiv]

By focusing his efforts on the instruction of children he hoped to found a new type of community, far removed from the old rivalries which had proved so destructive. Not that the text is a purely liturgical accompaniment, a vehicle for devotional assimilation of Christian truth. Cut in to the story are occasional questions from an enquiring Brahmin or ‘an intelligent person’, which enable the teacher to develop further the meaning of what has been recounted in the narrative.

There is, in other words, more to the Kristapurana than an imaginative retelling of the biblical narrative. Apart from the obvious influence of the Spiritual Exercises, we should not forget the one text that Ignatius allows his retreatant – The Imitation of Christ. Stephens’ novice-director, Fabio de Fabi, refers in his directory to the ‘hidden power‘ of the Exercises, ‘grounded as they are in the teaching of the saints, the truth of scripture, and long experience’.[xv] In good Ignatian fashion, the Kristapurana seeks to bring the powers of the soul and all the senses into a single whole-hearted response to the love of God poured out for humankind in Christ. This is no nod in the direction of ‘popular religion’; it is a sophisticated and highly effective catechesis.

The puranic style of story-telling

If the content is very much the Gospel story, the form or style in which it is recounted comes from the cultural world of Stephens’ brahmin converts. The word purana, literally ‘old’ or ‘ancient’, may be translated as ‘account of past history’.[xvi] It refers to a genre of Hindu literature which in its classical form is held to deal with topics such as creation, destruction and re-creation, the genealogy of gods and ancient sages, and the rule of kings and heroes. Puranas are lengthy stories associated with various theistic forms, avatars – literally ‘descents’ – or manifestations of Bhagavan, the ‘Blessed Lord’. Compared with the ancient Vedic hymns and the philosophical texts of the Upanisads, these are the most tangible expressions of the great movement of bhakti religion, with its seminal literary form in the Bhagavad Gita, the ‘song of the Lord’ the best-known and most beloved of Hindu scriptures.

Bhakti means ‘participation’ and may be loosely translated as ‘loyalty’ – with connotations of the divine grace that inspires all forms of heartfelt love. In their written form the puranas represent the imaginative ordering of exemplary stories. Their origins, however, lie not with the artifice of a writer but with the sutas or bards who were responsible for the oral recitation that gathered a community together. The form of semi-liturgical performance is still to be found all over India as the familiar stories are sung and recited in villages, temples and more formal settings.

Stephens used the form to exhort his audience to lead good and honest lives in imitation of Jesus Christ. But it would not have escaped his attention that the ritual which is inseparable from myths and legends has a certain political or social dimension. Sutas were often employed at court to celebrate ancient lineages and trace royal descent by linking the deeds of ancestors and heroes to the world of the gods. In terms of form the Kristapurana has such a religious and political purpose: the validation of the religious pedigree of the Christian community. The story proclaims who these people are.

The demands of justice

The first part of the text, about a third of the whole, is less the story of Israel than a single lengthy meditation on the coming of Christ as Saviour into a world darkened by sin. It is remarkably full, beginning with the rebellion of the angels and ending with predictions of the coming of Christ from Jewish prophets and Roman sybils alike. The second part, the Gospel narrative, begins with an invocation to God to inspire the teacher to speak worthily of the mystery of divine revelation before moving on to what Ignatius would call the ‘history’ of the Incarnation and the birth of Jesus.

I offer here just a couple of examples which may give something of the flavour of Stephens’ story-telling while at the same time pointing us in the direction of one of the major theological themes that emerges from this type of ‘puranic catechesis’.

When the three ‘rulers, kings of the East’ turn up (no mere wise men here), they are accompanied by elephants and chariots, massive umbrellas, flags and banners, war drums and the sound of trumpets. No wonder Herod was put out. ‘As if struck by a whip, or as the moon loses lustre, the king lost his demeanour and his lotus face faded. As if turned to a stone statue he could not utter a single word.’[xvii]

The kings meanwhile, with their pomp and magnificent array find their way to Bethlehem and the poor cowshed where the child lies on his mother’s lap. The encounter is movingly described and what they see of the humble surroundings of this king provokes something of a conversion as they remember how they have just promised Herod to report back on the whereabouts of the child. The next day they talk to each other about the dream they have had. They praise and worship the child and take their leave, sending the army back to their own country by ‘another way’ while they themselves disappear wordlessly off the scene.

It’s as if they had never been there. The streets of the city are silent and Herod blusters on about their finding nothing and having to return home ‘full of shame’. Inwardly, of course, he is consumed with envy, hatred and a desire for vengeance. He realises he has been deceived and eventually his anger bursts out. ‘Great flames rose into his insides [and] his brows were knit with knots. He shouted wildly and loudly in the palace and walked about like a mad man.’[xviii] The slaughter of the innocents is told in graphic detail. Jeremiah’s prophecy – ‘in Rama a voice is heard; Rachel weeping for her children’ – is quoted, but it is impossible not to imagine something of the dreadful events of Cuncolim playing on Stephens’ mind. There is, however, a sequel.

Having given a brief account of Herod’s further crimes and pondered on the sins of those who think they can ignore God’s justice, Stephens the suta is interrupted by a Brahmin. ‘Strange indeed’, he says, ‘is the story of that king. You have told a narrative of great moral value. So what punishment to such a king was given, to that unfortunate one by God? Tell us that, then we will understand.’[xix] The disease that afflicts Herod is described in gory detail and is not for faint European hearts. But it would have been pretty normal fare for an audience familiar with the grisly fate meted out to malign monsters.

This takes us back to the comment by the Jesuit historian. If there is one theme that underlies all Indian religion it is that of cosmic justice, the dilemmas of pursuing dharma, the cause of right, in a less than perfect world. In the Epic and Puranic literature this theme is played out as an endless battle between the personalised forces of good and evil. Very often it is the god-figure appearing in human or animal form who uses his superior powers, often gained through acts of asceticism, to overcome the wiles of the demon. This is the basic framework with which Stephens works. But he does more than set up a binary opposition, as becomes clear when he turns to my second example, Stephens’ magnificent rendering of the Temptations of Jesus.

Inside the hollow dome of the sky, the servants of Lucifer were talking. ‘Who is that dwelling, dressed like an ascetic, in the forest? … He is definitely the enemy. Now let us alert our king.’

While they were talking, the messengers said to Lucifer; ‘O King, why are you still sitting quietly? … We have seen a wonderful thing, a man has come suddenly leaping from the town of Nazareth.

‘We have seen him from far off but we dared not go close to him. His name alone is terror for all the devils.’

Upon hearing this, Lucifer trembled with great anger, as if fire was stirred up by sprinkling ghee on it.

Or like a cobra when it is put in a bamboo box … great wrath provoked him; from his nose, mouth, ears and out of all the organs, fireballs rushed and showered forth.

As a fierce rocket, when it is burst, it shakes a lot and looks as if there is no end to its fire … in the same way the fierce tormentor was greatly wrathful. At the place of hell, on the throne of fire he raged upon the chains as he shouted.[xx]

This Lucifer dominates the minor demons and they follow him because of their ‘pride and vanity’. But when he comes close to Jesus he covers up his ‘ghastly appearance’ and takes the form of an old man. This is Stephens’ version not of classical Hinduism but of a very Ignatian theme.

Discerning the dark side of human nature

Ignatius knew from his own experience that ‘the enemy of our human nature’ is a master of disguise; the evil spirit often appears as an ‘angel of light’, producing a counterfeit sense of well-being, disguising the morally dubious as the entirely plausible. What we take for peace and contentment may turn out on closer inspection to be a self-interested satisfaction or a lazy complacency. As Stephens tells the story, it is Jesus who beats the devil at his own game, allowing himself to get close to the demon in order to destroy him ‘stealthily’. This gives Stephens the opportunity to introduce a familiar patristic image:

As a fisherman puts bait of flesh in the mouth of fish, and when the hook is seized, he draws it up and takes his life, so the Lord whose wisdom is deep, allowed his human form to be carried, to vanquish the wicked one by the power of his Divine Nature.[xxi]

The theological motif of the divine entering deep into a world terrorised by the demonic runs through much of Stephens’ narrative. What he describes so vividly is the redeeming action of the Trinitarian God who, in Ignatius’s meditation on the Incarnation, looks down ‘over the vast extent and circuit of the earth with its many and various races’.[xxii] Stephens himself would have contemplated the rituals and devotions of the people of Salcete as well as its recent history and found there many resonances that would build up his form of ‘puranic exegesis’. But that is not to say he would have failed to spot areas of discord, where his Christian faith jarred with what he found in the local religious culture.

There’s a dispassionate side to Stephens’ flights of fancy which always come back to Ignatius’s insights into our flawed human nature. So easily we act as if good and evil operate in black and white terms when the truth is they mingle in many shades of grey. It would be surprising if Stephens were not haunted throughout his life by what happened at Cuncolim. And yet this extraordinary text is characterised by a lack of polemic. There are plenty of enemies and they get their comeuppance, but they are simply more or less culpable versions of Satan – and it is the unmasking of Satan, naming evil for what it is in all its shifty greyness, that most concerns Stephens.

The puranic world-view is by no means clear of binary thinking; forces of power and violence are forever coming up against qualities of love and wisdom. The question is how they work together – and Stephens’ answer unsurprisingly lies with the person of Christ. Schooled in the Spiritual Exercises and familiar with Ignatius’s great meditations on Christ the King and the Two Standards, Stephens offers not a translation of Christian faith into Hindu terms, still less a Christian-Hindu synthesis, but something more direct: an exercise in devotional rhetoric designed to appeal to a particular audience.

Scripture and understanding

The Kristapurana provides the people of Salcete with a sense of Christian belonging which does not do violence to their Indian culture. This is what becomes possible when the Word of God is taken seriously as an invitation to ponder the depths of the mystery that God contemplates. In the hands of a master story-teller like Stephens, scripture is not a script to be read and dissected but the place where God’s Word and the promptings of the Spirit are to be discerned. Scripture creates a religious world – and by entering into that world, with all its colour and symbolism, beauty and aesthetic power, one acquires a language which structures and interprets that world.

The story stands on its own merits; its truth does not have to be proved by subtle arguments which exist apart from that story. It speaks for itself, with the occasional addition of well-reasoned commentary – the questions raised by the ‘intelligent person’ (one of his Rachol brahmin converts perhaps?). Let the last word belong to this extraordinarily creative yet mysteriously laconic Englishman. This is what he says by way of self-justification in his introduction.

No efforts whatsoever have been made in this Purana to prove that their sacred book is untrue and false, and our sacred book is true and real. The difference and the distinctness between the two automatically becomes evident to all. The sacred book of the Christians emerges as beautiful of its own accord. … If you read or listen to this sacred book, it would be enough. It will promote proper understanding of everything.[xxiii]

Fr Michael Barnes SJ is Professor of Interreligious Relations at the University of Roehampton.

[i] Francs Correa, ‘The “Shakespeare” of the Konkan coast: Fr Thomas Stephens SJ (1549-1619)’, Vidyajyoti, 83 (2019), pp 461-71.

[ii] Kristapurana of Father Thomas Stephens SJ, translated and edited by Nelson Falcao SDB, Kristu Jyoti Publications: Bengaluru; 2012.

[iii] Letter quoted in Philip Caraman, Henry Garnet,1555-1606, and the Gunpowder Plot, Longmans; 1964; p 14.

[iv] Formula of the Institute 3.

[v] Reproduced in Falcao’s edition of the Kristapurana; Appendix 8; pp 1659-1663.

[vi] Ibid Appendix 9, pp 1664-1670.

[vii] Georg Schurhammer, ‘Thomas Stephens 1549-1619’, The Month, April 1955; pp 197-210.

[viii] Teutonio de Souza, ‘Why Cuncolim Martyrs? An historical re-assessment’, in Jesuits in India: a Historical Perspective, Xavier Centre for Historical Research, Goa, 1991.

[ix] Schurhammer, Stephens, p 202.

[x] Falcao, Kristapurana, Appendix 9; pp 1664-1670.

[xi] Ananya Chakravarti, ‘Christ in the Brahmapuri: Thomas Stephens in Salcete’, in The Empire of Apostles: Religion, Accommodatio, and the Imagination of Empire in Early Modern Brazil and India, Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018; pp 178-227.

[xii] Kusumawati Deshpande, A History of Marathi Literature, Pune: Sahitya Academi, 1985; p 21.

[xiii] As well as background material and notes, Falcao presents the text in columns, the Marathi (in Roman script) and his English verse translation facing each other. He also gives us something of the textual tradition, insofar as that can be reconstructed.

[xiv] Falcao, Appendix 10; pp 1671-1673.

[xv] Directory of Father Fabio de Fabi in Martin E Palmer SJ, trans and ed., On Giving the Spiritual Exercises: The Early Jesuit Manuscript Directories and the Official Directory of 1599, St Louis: The Institute of Jesuit Sources; 1996; p 197.

[xvi] See Friedhelm Hardy, The Religious Culture of India, Oxford: OUP; 1994; p 266.

[xvii] Part Two, Prasanga/Chapter 10; 16-17; p 708.

[xviii] Part Two, Prasanga/Chapter 13; 7; p 749.

[xix] Part Two, Prasanga/Chapter 13; 72-73; p 758.

[xx] Part Two; Prasanga/Chapter 20; 16-30; pp 843-44.

[xxi] Part Two; Prasanga/Chapter 20; 66-67; p 849.

[xxii] Spiritual Exercises 103.

[xxiii] Prose Introduction, p xci.