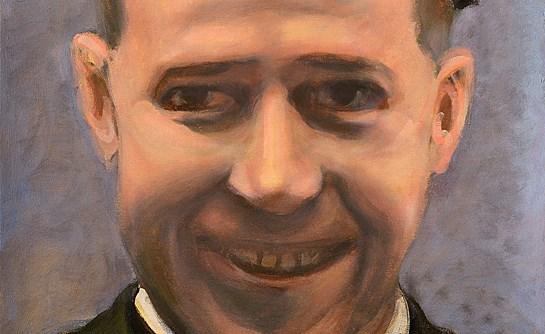

Have you been following the Jesuits in Britain’s 2014 calendar to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the restoration of the Society of Jesus? For the month of August, the featured Jesuit is Alberto Hurtado, who became Chile’s second saint when he was canonised in 2005. Damian Howard SJ recounts how he came to a fuller understanding of the true nature of humility by exploring Hurtado’s writings and story.

It was back in 2005 that, to bring to an end the long period of formal Jesuit training (‘formal’ because everyone knows that real training goes on until you are six foot under…), I was lucky enough to be sent to Santiago de Chile for the six month programme of study and prayer Jesuits call ‘tertianship’. That year, a landmark event in the life of the Chilean Church was due to take place: the canonisation in Rome of Chile’s second ever saint, a Jesuit priest called Alberto Hurtado. Padre Hurtado, as he was known throughout the country, had died as recently as 1951, well within living memory. There was a sector of Santiago that bore his name and he had become the kind of hero that Latin cultures quote endlessly and admire. With a huge celebration in Rome in the offing, Hurtadomania was the order of the day and no group was more caught up in the excitement than my brother Jesuits. It is not every day, after all, that someone you know well, a member of the family, if you like, is raised to the altars.

Hurtado was an unusually gifted man, of that there was no doubt. He seemed to have shuttled between an astonishing array of activities, so varied that each one of them could have demanded his attention for a lifetime. He had, like any other Jesuit, followed a lengthy period of intellectual and spiritual formation. In addition, he had studied for a European doctorate in education. He involved himself in issues of social policy, trades unions and poverty. He took a keen interest in the life of the Church and wrote articles challenging the bourgeois assumptions of fellow Catholics. He founded a journal, Mensaje, which is still published today. He gave retreats and spiritual direction that changed the lives of countless people. Most enduringly, he worked tirelessly for the poor and marginalised, setting up a charity called Hogar de Cristo, an enterprise which is still a going concern today.

Hurtado had, in other words, a comprehensive vision of the Gospel. He knew that Jesus Christ called forth a response from both head and heart. More than that, he wanted to find ways, as many ways as possible, of serving the Gospel in a very concrete way, with his hands as well. And it almost didn’t seem to matter to him if some of these ways were apparently trivial, as long as he was doing it all for Christ. It’s not that unusual to find people who say that they are trying to serve the Lord. But most of us want to do it in a way that suits us, which is to say by pursuing a single excellence to which we can devote ourselves. Not so with Hurtado. Intriguing…

Thanks to a grave character defect, I harbour a moderate aversion to heroes. Hurtado was clearly a hero to great crowds of Chileans, so a kind of unreflective, default antipathy kicked in within days of my first exposure to him. Big mistake. Hurtado was, as I would later discover, a man whose holiness manifested itself not so much in martyrdom, learned preaching or moral purity (though these were intensely present in his life) but in the way he had learned to act in the service of God, a way that spoke of a vibrant freedom from the compulsions that dominate more ordinary lives. And in this, had I but known it, I stood to learn a great deal.

Instead of which, I indulged myself by feeling irritated by what I saw as his tiresome drivenness and his moralising activism. It didn’t help that powerful people were busy squabbling over his legacy or that his cardboard face gazed down at me as I trundled along the supermarket aisles, nor, yet, that a series of slogans and soundbites had attached themselves to him: ‘what would Jesus have done?’ ‘Is Chile still a Catholic country?’ So it was that, to my shame, I chose to bury my head in the sand and so kept out of Padre Alberto’s way.

It was only months later, having returned home to London, that I found myself leafing through a collection of his writings, short pieces, articles and speeches he had written. As I read, I noticed the spirits starting to move. One piece in particular cut straight to the quick. It was a personal reflection from 1947 entitled ‘The Man of Action’ and something in it touched me deep down inside.

***

It is necessary to arrive at total loyalty. To absolute transparency, to live in such a way that nothing in my conduct might rebuff the inquiry of men, that all might be open to inspection. A conscience that aspires to such rectitude feels within itself the least deviation and deplores it: it focuses within itself, humbles itself and finds peace.

That sounded pretty demanding. Not much chance of my ever getting there. Living an absolutely transparent life? To my mind, that sounded like living a life without sin: impossible!

But that’s not quite what Hurtado was saying. It’s more that, as and when sin crops up, be it as something you are tempted to do or as a fait accompli, what counts is how you deal with it: sensing the ‘deviation’, you deplore it and then ‘humbling yourself’, in the process finding peace. But what does it mean to humble yourself…? A good sign: I was beginning to struggle with the saint’s words and finding his spiritual mentoring strangely compelling.

I must always consider myself a servant of a great work. And because my role is that of a servant, I will not reject the humblest tasks, modest tasks in administration, even the cleaning… Many aspire to have quiet time to think, read, prepare great things, but there are tasks that all reject, may these be my preferences. Everything must be accomplished if the great work is to be realized.

Keeping in sight the great work to which my own efforts are a small contribution: that’s common sense. But then the reflection becomes rather uncompromising. It’s not a comfortable thought. How many times had I excused myself from menial, humdrum tasks with the specious excuse that my training had put me above that sort of thing? And yes, hadn’t the priority at the back of my mind, lurking in the shadows where it’s hard to discern the truth, often been what would give glory to me? Writing something brilliant and original, or acquiring an encyclopaedic knowledge of some complicated subject that would lend me a fine reputation? Should I really prefer to perform the unseen, un-praised chore? ‘Yes, you should…’

Humility consists in inserting yourself in your true place. Before people: not by considering myself the least among them, because I do not believe this; before God: by recognizing continually my absolute dependence with respect to Him, and that any superiority I might have in the sight of others comes from Him.

What an insight that was, how honest and real. The ‘humility’ I had understood I was to aim at was about seeing others as always better than me. I hadn’t been terribly successful in acquiring it, you understand. But how much more difficult was the life-giving humility Hurtado was evoking. It would mean knowing myself really well, taking responsibility for my gifts rather than finding excuses for not using them, and accepting the inevitable ego-damage that comes with correction. I might even have to learn from failure without the compensating histrionics which have not infrequently been my trademark.

What I was slowly coming to realise, as I continued to read, was that St Alberto really lived out the Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits. He had found a way of expressing the kind of practical spiritual wisdom that Ignatius had passed on to his brothers. And what he had discovered and articulated was radical and demanding and surprisingly attractive. It reminded me of why I had joined the Jesuits in the first place, why I had fallen for a spirituality that put me in touch with God on a daily basis so that minute by minute I might live as a companion of Jesus, receiving the grace of his encouragement, yes, but also finding myself corrected, challenged and put firmly back on the right track.

It’s easy in the spiritual life to settle for some cheap version of what we aspire to, a phony kind of holiness. It’s why we need the lives of the saints to show us the real thing so we can let God put us back together: words and thoughts, prayer and action, all combining to make a coherent life offered in its entirety to the Lord. No mean feat, that. It requires nothing less than total transparency to God. For only such a transparent soul could have seen the almost concealed egotism that hesitates to think big for God:

Munificence, magnificence, magnanimity, three words almost unknown in our times. Munificence and magnificence do not fear the cost of realizing something grand and beautiful. They do not think in terms of investing and filling the pockets of their supporters. The magnanimous person thinks and acts in a way worthy of humanity: he does not belittle himself. He who does not think big, in terms of all men, is already lost. Some will tell you: Careful with that pride!… why think in such a big way? But there is no danger: the greater the task, the smaller one feels. Better to have the humility to begin great tasks with the danger of failing, than to reduce one’s goal out of pride in order to guarantee success.

Damian Howard SJ