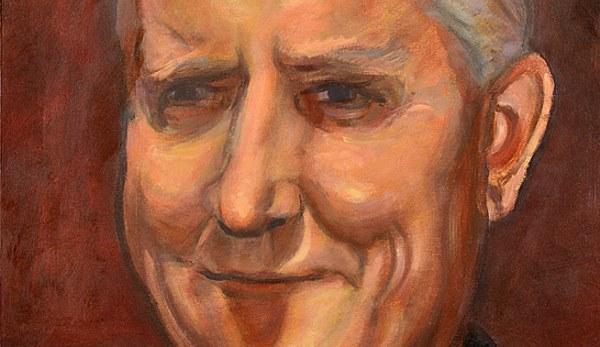

The final Jesuit to appear in the 2014 calendar of the Jesuits in Britain is a priest of the New York Province whose mission to Russia led to him serving 15 years’ hard labour in prison camps. Meet Fr Walter Ciszek and read his incredible story, as told by Michael O’Halloran SJ.

In 1929, Pope Pius XI’s concern for the people of Soviet Russia led him to write a letter ‘to all seminarians, especially our Jesuit sons’. In it he outlined his plans for a new formation centre in Rome to prepare volunteers for possible future work in the re-evangelisation of Russia. Jesuit novice-masters all over the world communicated the pope's letter to the men in their charge. Among the novices made aware of it in New York was Walter Ciszek, who wrote of his immediate reaction: ‘I knew it from the beginning ... and that feeling grew until at the end I was fully convinced that Russia was my destination. I know, I firmly believe, that God wants me there and I will be there in the future.’

Walter was then 25 with more than a year ahead of him before he would take his first vows as a member of the Society of Jesus. The son of Polish immigrant parents, he was immensely proud of that heritage and of the inflexibility of purpose - or stubbornness! - that it brought him. Just a few years before, when he was studying for the priesthood at a diocesan seminary, he read the life of the young Polish novice, St Stanislaus Kostka. He decided – inflexibly! - that he must be a Jesuit, because in that story he could find someone to admire and in whom he recognised, even three and a half centuries later, traits of character that were just like his own. Despite strong objections from his father, Walter left the seminary and entered the Jesuit novitiate. No-one in the Society of Jesus gave him anything but wise support and yet he was not beyond reminding the Superior General of the Society (whose name, encouragingly enough, was Ledochowski) from time to time that he was an enthusiastic volunteer. He continued his course of formation in the New York Province of the Society and then in 1934 was overjoyed to learn that he was being sent that summer to Rome to begin his studies of theology at the Gregorian University, and with special studies in Russian language and liturgy at the new Russian centre, already known as the ‘Russicum’.

Walter found among his companions at the Russicum a native Russian, a Belgian, three Englishmen, three Spaniards, two Italians, a Pole and a Romanian. His biggest trial was getting to grips with the Russian liturgy of the oriental rite, the rite in which they had daily Mass together, but his determination saw him through. Walter and his Russian confrère were considered by the others as outstanding for their zeal and sometimes were gently teased on that account.

However, the difficulty, danger and unpredictability of the mission to Russia was brought home to Walter very soon after his ordination in 1937. He was told by Father Ledochowski that it was proving quite impossible to get priests into Russia. That meant that his first appointment would have to be to minister to Poles of the oriental rite living in a town not very far from the Russian frontier. Walter mastered his disappointment and before long was on his way, no less determined, no less full of zeal. Very soon after his arrival in the town of Albertin, everything changed. It was 1939 and there had been talk of war for some time. On the one hand was invasion by Nazi Germany, and on the other annexation by Soviet Russia.

Having begun his ministry in a Polish town with Polish people, Walter was now de facto in Russian territory and it was as if a door had been opened for him. As a priest he was not allowed into Soviet Russia, but as one of many Poles on the move, he could seek the work now being promised to such people in the Russian Urals.

He had valid Polish identity papers and was passing himself off as a man whose wife and children had died in a German air raid, and who was now seeking work and a new life. Of great help to him was the ease with which he dealt with others - Russians or Poles, Christians or Jews, people with a longing for their religious past or brain-washed into a hatred for anything to do with God. But there was always the unease of living out a lie and the fear of discovery. In fact, it was not long before he found himself under suspicion. With no explanation, he received an order to board a train for work in the lumber yards at a place called Chusovoy.

Walter adjusted to life and work in this new town, but at three o’clock one morning, he and his companions were all arrested as German spies and marched off to jail at gunpoint. The place was called Perm; here, Walter was interrogated repeatedly and on more than one occasion beaten with rubber clubs to persuade him to agree that he was indeed a German spy. What really startled him was that the interrogators knew all about him - American, Jesuit priest, his real name, places of study - and since Germany had now invaded Russia they wanted confirmation that he was spying for the enemy. He was condemned to fifteen years’ hard labour.

Much later on in his life, Walter wrote a book about his experiences, entitled With God in Russia. In that country he would discover the abiding truth of his Jesuit vocation: that in all circumstances and no matter what life might throw at him, he was a companion of Jesus and that Jesus was a companion to him. That was the basis of his spiritual life. Physically he had always been a fit and active man with a strong constitution, gifted at sport and devoted to daily exercises to keep himself trim. He was going to need all of that to survive the years ahead: the daily grind of exhausting physical labour in prison camps, the extremes of heat and cold, appallingly little food and very rarely having anyone to talk to about what was most important to him. He knew that he had to find ways of making praying possible.

The first four years of his sentence were spent in Moscow jails, mostly in solitary confinement but on occasion sharing a cell with other prisoners, one of whom was the Russian from the Russicum who had been such a companion to him. Walter’s happiness at this chance arrangement was based on more than simply a reunion of friends – it allowed the two Jesuits ‘... to attend our regular spiritual duties - weekly confessions, morning and night prayers, a sermon every Sunday’. He wrote of the way in which he and his brother Jesuit understood their vocation at that time: ‘In effect our work had to be our prayer. We used to grin wryly sometimes as we reminded each other we were truly being “contemplatives in action” doing everything we did, as St Ignatius says in the Spiritual Exercises, for the greater glory of God. We were working not only to get food to stay alive, or to be accepted by the men, but because for the time being work was our “vocation”, our “ministry”. We were workers’. But a parting was inevitable, and one day Walter was yet again interrogated along the familiar lines, except that now he was accused of being a spy for the Vatican. It was the last such interview and after it he was bound for the station and for a train to Siberia. He never saw his Jesuit friend again.

When working at the back-breaking toil of loading and stacking coal at a place called Dudinka, well within the Arctic Circle, Walter wrote of his joy at being discovered by a Polish priest from another barrack: ‘He found me before I had had a chance to look for him and asked me if I wanted to say Mass. My last Mass had been said more than five years ago’. In the other priest’s barrack the men were mostly Poles; they revered and protected the priests, and Walter tried to say Mass for them at least once a week. They made wine out of raisins stolen from the docks and altar breads from flour ‘appropriated’ from the kitchen. The chalice was an old whisky glass. In his later account of his years of hard labour, his joy at having been able to say Mass with a congregation is evident; along with the small kindnesses he received from some fellow prisoners, it reminded him of why he was there in Russia. This joy stands in stark contrast to his plight in the long, barren years when he had no such companionship.

Walter was sent for one day to be told that he would be free in ten days’ time. By then he would have served fourteen years and nine months of his sentence but was entitled to a remission of three months for ‘exceptional work’. On the day of his release, Walter signed various forms, was given new papers and allowed to leave. He walked to the station and took the train as directed to Norilsk, a place where he had worked on construction work some years before. It had grown in the meantime and was now quite an industrial centre. He had the address of a priest and was given the warmest of welcomes by him. From then on he was very involved in the Catholic life of the area: ‘On Sundays with a valise packed full of Mass equipment I’d go to one of the old barracks which had housed prisoners when I had been there. Now it was part of the city housing and I said Mass there at nine for the “parish” of Poles. Before Mass there were confessions and after Mass baptisms and weddings - in ever increasing numbers as people found out that I’d be there regularly’.

Walter was helped to find work in a laboratory and became a union member. That was a very happy time for him, but eventually a combination of unwarranted suspicion and bureaucracy meant that he had to leave, first for Krasnoyarsk and then for Abakan. By now he was in contact with the American Embassy in Moscow and with his sisters in America who had supposed that he had died sometime after 1939. But there is not the slightest suggestion in his writings that he contemplated a visit back home. He knew with total conviction that God had called him to Russia to do all he could to work at the re-evangelisation of its peoples.

It comes as no surprise, then, to learn that Walter’s return to the United States was not of his volition. Without his involvement, arrangements were made for him to be taken to Moscow, where he spent some time in the care and company of a courteous KGB man, who allowed him one afternoon to visit Lenin’s tomb. Shuffling past the glass coffin with the long line of Russians and foreign tourists, Walter said a prayer for Lenin, thinking, ‘He was a man after all and he may be in need of more prayers than he's getting here’. Still no one had told Walter that he was going home, but in fact he was one of two Americans who were being exchanged for two Russian agents who had been caught about their work. And so he returned to the United States.

At the beginning of With God in Russia, Walter says that he is writing it principally in response to two questions people kept asking him: ‘What was it like?’ and ‘How did you manage to survive?’ The answer to the first question is in his admirable descriptions of people and places, and to the second is an underlying presence of God.

Walter was guided always by the wisdom of St Ignatius presented in the Spiritual Exercises. He had chosen to place himself entirely at the side of Christ and under his banner and there he remained. He knew that throughout his life he had been in God’s hands and never more clearly than during the darkest days of his time in Soviet Russia. Although it was not his choice to return to the United States, his leaving Russia meant that a Russian man, quite unknown to him, would be returning to his loved ones. Walter will have rejoiced in that.

Fr Michael O’Halloran SJ