The readings from Isaiah that we heard at the Easter Vigil put Karen Eliasen in mind of a song which can help us make sense of Pope Francis’ call for the Church to be a ‘convincing herald of mercy’. The prophet is just such a convincing herald because he reminds us that ‘God is a God of mercy and justice, and his business with us is ongoing in its love and pain’ – how does he do this?

A few years ago the BBC and PBS ran a television crime series, Case Histories, based on novels by Kate Atkinson. The hero of the books and the show is Jackson Brodie, a policeman-turned-freelance detective with a penchant for impulsive violence in the face of injustices, but also a proverbial heart of gold that cannot say no to people in distress. Especially as played by Jason Isaacs, he is an appealing mix of physical hunk and emotional mess who likes to listen to slow, sad American country music, which featured heavily in the show at the suggestion of the novelist herself. Atkinson, a keen country music fan, has described how she is in the habit of letting a playlist ‘evolve’ for each novel, a playlist which ‘somehow points me to something essential at the heart of each book.’[1] Enjoying the TV series and its shimmering shades of justice and mercy, I found myself paying attention to the background music as much as to the hunk and the histories, not least when great songwriter Mary Gauthier’s Mercy Now (watch and listen below) turned up in the first episode.

In spite of its title, Mercy Now has nothing immediately hymn-like about it, its more natural performance setting being small-town café rather than chapel. It is a softly plaintive ballad, long and slow in its use of a simple melody and a simple progression of ideas around who needs mercy – from ‘my father’ whose work is almost over in the first verse, through to ‘my brother’ who lives in pain and ‘my church and country’ who are sinking into a poisoned pit, to ‘every living thing’ racing towards a mushroom cloud, and finally in the last verse to ‘every single one of us’ who are hanging and dangling between ‘hill and sacred ground’. As the song moves steadily from the personal to the universal, the last verse finishes up with a terrible, familiar conviction about the human condition: ‘I know we don’t deserve it, but we need it anyhow’. Nothing truer can be said of Holy Saturday night.

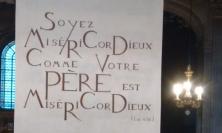

I am hard put to find any other popular medium that so effectively articulates Pope Francis’ recent exhortation to the Church to be a ‘convincing herald of mercy’[2] as that ballad Mercy Now. When I hear Mary Gauthier, a plain, unadorned woman with a plain, unaffected southern drawl, singing this plain, unembellished ballad recognising that every single one of us, from our father and brother to our Church and country to all living things, could use a little mercy now, I am thoroughly taken in. And sitting in the chapel on Holy Saturday night listening to the Easter Vigil readings, I am brought to mind of Mercy Now.

Embedded in the Easter Vigil’s Liturgy of the Word, represented by no fewer than three different extracts, we find one of the Old Testament’s most passionate exemplars of a ‘convincing herald of mercy’: the prophet Isaiah. Holy Saturday night, in its grand sweep through some highlights of the Old Testament’s salvation narrative, offers us a couple of familiar Isaiah texts on mercy (or variations thereof): ‘But with everlasting love I have taken pity on you, says the Lord, your redeemer’ (Isa 54:8, in the fourth reading) and ‘Let him turn back to the Lord who will take pity on him, to our God who is rich in forgiving’ (Isa 55:7, in the fifth reading).[3] Of course from the Book of Isaiah we can probably all effortlessly enough fish out many familiar examples of some of the most consoling poetry anywhere in Scripture; it is the very thing we so often turn to Isaiah for. But this is cherry-picking; there are other things to be found in Isaiah, and I wonder if these other things can shed some light on how we can better understand what it means to be not just a herald of mercy, but a convincing one.

Were we to take the trouble to read through all of the Book of Isaiah, we would quickly realise that taking up far more space than consoling themes of mercy (and love and pity and forgiveness) are unsettling themes of justice (and anger and condemnation and punishment). Any serious take on God’s mercy at work in extremis cannot ignore these other more space-consuming texts, and in fact the Vigil readings do not do that. Included in the fourth reading is this extraordinary admission from God himself: ‘In excess of anger, for a moment I hid my face from you’ (Isa 54:8). The usual prophetic explanation of what has gone so horribly awry between God and Israel – that Israel has done the deserting – is turned on its head. Here it is God who has, in a moment of anger, done the deserting. In extremis, God does get angry, and as he owns up to in that same Isaiah passage by his reference to Noah and the flood, he can do more than hide his face, he can become destructive. It is a paradoxical image of God that has roots all the way back in Israel’s original Mount Sinai experience of God in Exodus 34:6-7: ‘God of tenderness and compassion, slow to anger, rich in faithful love and constancy … forgiving fault, crime, and sin, yet letting nothing go unchecked’. Now in deutero-Isaiah, in the time of the Babylonian Exile many centuries after the Sinai experience, this same God’s sense of the inseparable pairing of justice and mercy, of love and anger, is still very much alive and kicking, as is his insistence to let ‘nothing go unchecked’. There are consequences to how we behave, and those consequences may be merciful or they may be violent.

How to reorient towards a both/and scenario – a God who is both merciful and violent? That is not my God, we may vehemently protest. Yet this is what the Book of Isaiah presents us with; and it is what the Easter Vigil narratives present us with.

Nowhere in the Old Testament can we escape the inseparability of mercy and justice, of God’s love and God’s anger. Like Siamese twins sharing vital organs, the pair cannot be separated and be expected to live. ‘Mercy without justice is the mother of dissolution; justice without mercy is cruelty’, Thomas Aquinas summed it up, as if the clear choice is between chaos and fascism. But this kind of summation tells us little about how such a pair can enter into our religious imaginations as a wholesome rather than pathological combination. The Book of Isaiah colourfully emphasises the pair’s inseparability, and does so to a shocking degree. Any image of wholesomeness may be the last thing stirred up in the imagination of the reader of the entire Book of Isaiah, because what so flamboyantly flares up in Isaiah when the talk turns to God’s justice is the blood-stained warrior God who announces: ‘So I trod them down in my anger, I trampled on them in my wrath. Their blood squirted over my garments and all my clothes are stained’ (Isa 63:3). If the Book of Isaiah is where we fish for the very finest of what Scripture has to offer on a loving and merciful God, it also where we are exposed to the very gruesomest of what Scripture has to offer on an angry and vengeful God. We do not encounter the merciful God without also encountering the powerful warrior God, the one who, to use a classical Old Testament term, ‘delivers’ us. Judges, kings, messiahs, saviours, indeed heroes of all kinds – these all do this one great deed, they deliver us from the enemy, and in the process they shed blood. Deliverance is the one mighty deed of God’s that fuels Israel’s continued faith in him. It is a theology bluntly expressed by the young American edge-philosopher Criss Jami: ‘The reality of loving God is loving him like he's a Superhero who actually saved you from stuff rather than a Santa Claus who merely gave you some stuff.’

We may be tempted to exempt our own Jesus meek and mild from the bloody metaphors of this Superhero stuff. But we should keep in mind the Vigil of Holy Saturday and what we imagine is going on in that time of waiting – as Christians we believe that he ‘died, and was buried. He descended into hell’ – and whatever Jesus, whose name in Hebrew means ‘Yahweh delivers’, does down in hell, it delivers us, it saves us. The ancient imagination was far less squeamish about describing what Jesus may have been up to as a deliverer down there, and in the Office of Readings for Holy Saturday we get a text that makes no bones about the power of what that was. That text is an extract from the stirring ‘ancient homily for Holy Saturday’ in which we read: ‘Greatly desiring to visit those who live in darkness and in the shadow of death, he has gone to free from sorrow the captives Adam and Eve, he who is both God and the son of Eve. The Lord approached them bearing the cross, the weapon that had won him the victory.’ I would venture to call this image of the cross as a weapon Isaianic. And Exodusian – in the Easter Vigil reading just before we hear from Isaiah, we get the full thrust of God the warrior in the victory song of Moses: ‘Horse and rider he has thrown into the sea … The Lord is my salvation. This is my God … The Lord is a warrior’ (Exo 15). If we hold this relationship between Isaiah and Exodus in mind as we return to reading all of the Book of Isaiah, we should not be surprised that the very end of Isaiah makes this relationship painfully explicit. Should we take it into our heads to ask embarrassing questions about God’s mercy and the dead Egyptians, Isaiah reminds us that, yes, peace for all humanity who come to bow before Yahweh, but the threat of his anger remains in force: ‘And on their way out they will see the corpses of those who rebelled against me; for their worm will never die nor their fire be put out, and they will be held in horror by all humanity’ (Isa 63:24). Thus ends the Book of Isaiah, a prophet who nevertheless, with his many nuggets of consoling love poetry, remains for us a convincing herald of mercy. God is a God of mercy and justice, and his business with us is ongoing in its love and pain. So we return to the Easter Vigil every year, and so we pray continually for deliverance with the final words of the New Testament, ‘Come, Lord Jesus’ – for every single one of us could use some Mercy Now.

Karen Eliasen works in spirituality at St Beuno’s Jesuit Spirituality Centre, North Wales.

[1] See Atkinson’s comments, and a list of all the wonderfully mournful American country songs used on the series at www.pbs.org/wgbh/masterpiece/casehistories/music.html

[2] Pope Francis, Misericordiae Vultus (2015), §25.

[3] The third Isaiah text in the Vigil readings is the responsorial psalm after the fifth reading, from Isa 12:2-6, ‘Truly God is my salvation …’.