‘O if we but knew what we do’, wrote Gerard Manley Hopkins as he despaired over the way in which he saw the natural world suffer at the hands of humankind. This attentiveness to and solidarity with the suffering of a fragile planet and its most vulnerable inhabitants is a Spiritual Work of Mercy, writes Teresa White FCJ: comforting the afflicted is at the very core of what it means to be merciful.

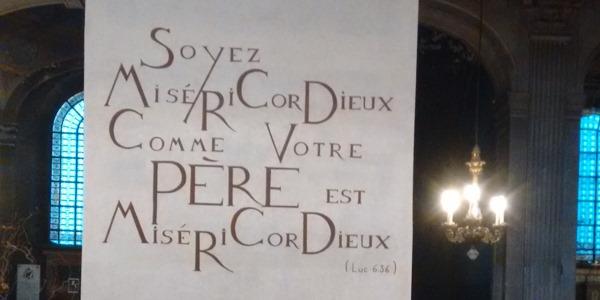

Recently, a friend of mine spent a few days in Paris, and on her return she told me that one day she happened to find herself near the church of Saint-Sulpice. She popped in for a visit, and beside the Jubilee Door of Mercy she saw a large inscription, unadorned but unignorable: Soyez miséricordieux comme votre Père est miséricordieux – ‘Be merciful as your Father is merciful’. The text, which my friend captured in the photo above, recalls the etymology of the French word for ‘merciful’ and nudges the reader to consider its significance. In French, as in Latin, it is possible to ‘play’ with the word by separating and thus accentuating its three components, and here this is done through the lettering, which brings the spiritual meaning into clear relief: MISÉRI - COR - DIEUX: to have a heart (cor) open to those in need (misère), and to desire to combat and overcome their suffering just as God (Dieu) enters into and attends to this human suffering. It seems to me that all truly merciful behaviour is somehow encompassed in that explanation of miséricordieux; and of the fourteen traditional Works of Mercy, the one that seems to chime most resonantly with the concept of mercy as conveyed there is ‘to comfort the afflicted’.

Cardinal Walter Kasper, in his recent book, Mercy, holds that mercy is a fundamental issue for us today, living as we do, ‘with the threat of ruthless terrorism, outrageous injustice, abused and starving children, millions of people in flight … and devastating natural catastrophes’.[1] It is his view that these signs of our time point to a deep need for God’s mercy and protection in our world. Pope Francis takes a similar position and it is well known that mercy has become the leitmotif of his pontificate, for, like Cardinal Kasper, he sees in it the kernel of the Christian message: ‘mercy is the first attribute of God’.[2] As God is merciful, so we in our turn must be merciful. Indeed, an essential dimension of Christian involvement in the world is to respond sensitively to the concrete needs that we encounter and to offer comfort to those in distress.

On 19 March 2013, the Feast of St Joseph, protector of the Holy Family, Pope Francis urged everyone to be protectors not only of one another but of the natural world as well, for the whole of the biosphere of which humanity is an integral part also has concrete needs. Caring for our fragile planet and protecting it, he said, ‘demands goodness, it calls for a certain tenderness’.[3] However, with our growing powers to manipulate and exploit the material world, what it seems to need most protecting from is us.

Two years later, in Laudato si’, Pope Francis broadens and reinforces his vision to address environmental concerns head-on, insisting that our obligation to care for the poor and needy must also include the earth itself. He encourages us to cultivate what Thomas Berry called ‘a more benign mode of presence’[4], recognising that ‘never have we so hurt and mistreated our common home as we have in the last two hundred years’.[5] If we truly desire to ‘comfort the afflicted’ our acts of mercy and compassion should intentionally embrace not just the needs of humanity but of the whole of creation – the natural world is afflicted, too. This means examining our lifestyle, and, in the words of Patriarch Bartholomew, being prepared ‘to replace consumption with sacrifice, greed with generosity, wastefulness with the spirit of sharing’.[6]

Laudato si’ calls our attention to the fact that many of the ecological problems we face today are the result of human insensitivity to the environment. We have placed ourselves and our advancement at the centre of things, and by our amazing inventions have set in motion multiple changes so rapid that they do not give the earth time to adapt. Climate change has global, physical consequences, but because it affects the poorer countries far more severely than the richer, it is also a matter of social justice. In the spirit of ‘comforting the afflicted’, the developed countries are urged to seek effective ways to limit their consumption of non-renewable energy and assist poorer countries to implement policies and programmes of sustainable development. Since the earth’s ability to renew itself is not unlimited, Pope Francis emphasises that human activity is most effective when it is in accord with the natural functioning of the God-given eco-system into which it is inserted.

To be merciful, to comfort the afflicted, means to enter into the suffering of others, to walk beside them, to help them, to tend their wounds. Laudato si’ encourages us to broaden our horizons by extending this loving concern towards the natural world. Gerard Manley Hopkins does just this in many of his poems. His worldview is relational, and with his poet’s eye he looks upon created things with a contemplative gaze, sees the radiance of God shining in them. He agonises when, often unthinkingly, the countryside is destroyed or defaced by human activity. He does this with particular feeling in ‘Binsey Poplars’, in which he laments the felling of his ‘aspens dear’ in 1879. The second half of the poem reflects his longing for a deeper awareness of the abuse and misuse of our relationship with nature:

O if we but knew what we doWhen we delve or hew —Hack and rack the growing green! Since country is so tenderTo touch, her being so slender,… …even where we mean To mend her we end her, When we hew or delve:After-comers cannot guess the beauty been.[7]At the end of the day, just as we cannot love God without loving one another, how can we truly love one another without loving and respecting the earth which is our common home? In that home, as Pope Francis reminds us, ‘every creature has its own value and significance’[8] and it is our responsibility to meet the needs of the present ‘with concern for all and without prejudice towards coming generations’[9]. If we could attune ourselves to the inherent and profound harmony between God and everything that exists, then humanity would flourish in our evolving universe and we would learn how to live in blessed solidarity with the whole of creation.

Sister Teresa White belongs to the Faithful Companions of Jesus. A former teacher, she spent many years in the ministry of spirituality at Katherine House, a retreat and conference centre run by her congregation in Salford.

[1] Cardinal Walter Kasper, Mercy: The Essence of the Gospel and the Key to Christian Life (Paulist Press, 2014), p.1.

[2] Pope Francis, The name of God is Mercy (Bluebird, 2016), p.81.

[3] Pope Francis, Homily, 19 March 2013.

[4] Thomas Berry, The Great Work: Our Way into the Future (New York: Bell Tower, 1999), p.7.

[5] Pope Francis, Laudato si’ (2015), §53.

[6] Quoted in Laudato si’, §9.

[7] Gerard Manley Hopkins, ‘Binsey Poplars’ (1879).

[8] Laudato si’, §76.

[9] Ibid., §53.