‘Dance Me to the End of Love’

Twenty-five years ago I was marooned in a car just outside Belfast.

My friend, a multi-tasking nun, had to organise a number of things locally so I was left sitting, looking after the car, for the best part of an hour.

I had not planned ahead, so I had nothing to read: the radio was full of static and the collection of audio tapes was slim. But one caught my eye: an album of Leonard Cohen songs.

‘Everybody Knows’

Cohen was on the edges of my rather limited cultural radar. I couldn’t name a song, but I could have visualised the tableau: his brooding sultry looks, sitting in the gloom of a darkly-lit cubicle in a US diner, at a circular table surrounded by good-looking women.

In days when music was not so readily available, I had never come across anyone who actually listened to Cohen’s work and he never seemed to be played on the BBC. Since music was expensive in the ’70s (how did we cope without YouTube?!), as a student I had never even contemplated spending good money on buying a Cohen record to experiment with his darker chimes. I knew him as the brooding creator of ‘music to slit your wrists by’, and I stuck closer to Billy Joel and Gordon Lightfoot.

The tape in the Belfast car was a gentle revelation. It raised my Vulcan eyebrow just a single notch on the Roger Moore scale – but that was quite an achievement. Cohen was good. The lyrics were poetically clever, mysterious and articulated clearly; the music, although light-years away from ‘Dancing Queen’, was catchy and memorable in a weird sort of way. The voice was incarnate Christmas pudding and is, to this day, impossible to mistake.

‘I'm Your Man’

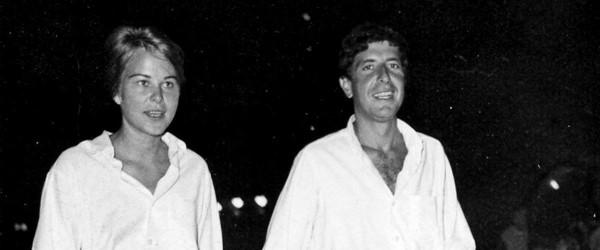

Nick Broomfield’s documentary, Marianne & Leonard: Words of Love, is an excellent introduction to the man and his life, seen through the frame of Cohen’s life-defining residence on the small Greek island of Hydra in the ’60s; and, in particular, through his relationship with Marianne Ihlen, his Nordic muse, friend and periodic lover. Broomfield rightly declares his interest: he too had been on Hydra, and had been a friend of both and a lover of Marianne.

Both Cohen and Marianne went to Hydra as refugees – he from a constrained Canadian upbringing, she to escape a youthful marriage in Norway. Axel, her young son, went with her and soon Cohen was the surrogate father.

The rustic Hydra (pronounced ‘Heedra’) was a magnet for the would-be lotus-eaters of the bohemian ‘60s, searching for sun, cheap lodgings and the loosening mores of a world in flux. For Cohen it was the crucible in which his illusions of creativity were finally burned off – it was on the island that he realised that his future was not as a novelist, but as a musical poet. (I once owned a copy of Beautiful Losers, the novel that emerged from the forge of Hydra. It was hammered out on the anvil of his typewriter, scorched by the Mediterranean sun and fuelled by copious amounts of LSD. Dear Reader: resist the temptation to secure your own copy for posterity – buy lottery tickets instead.)

When Cohen and Marianne first encountered each other, both were hamstrung by poor self-image; they were physically beautiful yet neither recognised that fact when gazing into a mirror. Hydra repaired that.

‘First We Take Manhattan’

Perhaps it was something of the growing self-awareness in Cohen that eventually led him away from Greece and back into the cultural ferment of North America in the late ’60s – his first tentative appearances on TV with Judy Collins and then the stoned, cultic appearance at the Isle of Wight festival in 1970. The myth began to be articulated.

Marianne and Axel followed him to the US, but the worlds were now diverging and (fitfully, painfully but eventually) they lived apart – she returned to Norway to a new marriage and a stable living. Suzanne – another Cohen muse – flits momentarily across the screen at this point; a darker beauty: more confident, more ruthless.

The documentary draws on rare archive footage and on an impressive gallery of talking-heads. We catch glimpses of Cohen’s sexual magnetism; we hear stories of the richly destructive, creative lifestyle, and anecdotes of the paradox of his personal warmth and unknowable distance.

‘In My Secret Life’

I found it particularly enlightening to hear about Cohen’s mother – extrovert, exotic, Russian and Jewish – and to realise you can detect all four flavours in his music.

Ron Cornelius, one of the regular musicians, speaks movingly as he recalls Cohen’s insistence that the band must go and play an impromptu free concert in an English mental asylum – memories ripple of Cohen’s own mental breakdown and his mother’s eventual committal, sharpening the solidarity with the damaged and the lost.

Cohen was a solemn pilgrim on the road of life. At one point in the ’90s, he was a Buddhist monk for six years and it was a serious commitment. He faced his later changing fortunes – bankruptcy, the loss of his youthfulness, the blunting of his energies – with an impressive equanimity, which feels genuine. He returned to performance in his later life because of necessity (he was swindled by his manager/friend) but he stayed touring because he enjoyed it, and his latter years were something of a lucrative Indian summer with a new generation of fans emerging.

The documentary is well-edited and moves along briskly. There are fragments of a number of his songs – the Mandrax-inspired set, with the tent on fire, at the Isle of Wight; the touching late concert in Oslo with Marianne in the front row – but I would have liked to have seen at least one full rendition of a Cohen song incorporated into the film. Although, perhaps not ‘Hallelujah’.[i]

‘Take This Waltz’

Overall Hydra seems to have been a place of healing for both Cohen and Marianne. They remembered it as ‘a time of kindness.’ But not all were so lucky. Despite the nostalgic nod to the free love, open marriage and the drugs, the film cannot hide the terrible damage wrought by the hedonistic lifestyle – most survived, a few thrived, but there was a heavy toll of suicides, addictions, abortions and breakdowns.

When the Apollo astronauts looked back at the Earth and compared it with the Moon they were circling, they were struck with the colour and the life that radiated from our planet: the atmosphere of oxygen and the water of the oceans shielding the Earth and providing protection from the hostile environment of space, with its deadly cosmic rays and the potential collisions with asteroids, meteors and comets.

Cohen in some ways was like fragile planet Earth – he sought the essence of existence and, despite the pounding and some serious self-inflicted wounds, he was graced with the basic elements of life. Ultimately wrapped in the folds of a protective atmosphere where nurturing was possible, he experienced repair.

‘Hey, That's No Way to Say Goodbye’

Less so, young Axel – Marianne’s son – who is something of an unresolved sub-plot in the documentary. Where is he now? Unlike the Hydra-adults, who had choice, the expat children clearly suffered from the instability of life on the island. For all the glitz and the colour of the love affair that takes centre-stage, Axel lurks uneasily in the shadows of the film: he never appears, the narration hints that he might be in care.

On reflection, as the credits roll, it is Axel who stays with you. He is like the Moon, silent and shaded in greys, somewhat forgotten in orbit around the gravitational circus that was Leonard and Marianne. Axel was loved and fed, but seems to have had little childhood stability or the calm anchorage that is essential for early human nurturing. He was clearly vulnerable and somewhat unprotected; every impacting meteorite left a dent, every boot-mark made a print with no winds or ocean to smooth and repair. A casualty of love?

At the end of the day, it is Axel you feel for most of all.

[i] Although it is his most successful song, I really don’t think he ever performs it well. ‘Heresy!’ you might say. ‘He’s the composer!’ Hmm… perhaps listen to George Gershwin characteristically mangle one of his own classics… https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B4QDsbucFxQ