The Easter Triduum begins on the evening of Holy Thursday, with the Mass of the Lord’s Supper. The first reading of that liturgy puts us in mind of the Passover lamb, whose blood became a sign of God’s fidelity to his people. Gerard J. Hughes SJ suggests that our understanding of Jesus’s actions at the Last Supper should be informed by this tradition and by the account of God’s command to Abraham to sacrifice Isaac.

The Last Supper is a key event in Holy Week; our commemoration of it in our Maundy Thursday liturgy sets the tone and is the background for everything else. If we think carefully about what Jesus did at that Passover meal we shall discover how important it was, and so have a better understanding of what he was trying to do on that fateful night and on the day of his death.

Sacrificing to God?

We use the word ‘sacrifice’ in both a very specific and in a more general sense. In the more general sense we can speak of parents making sacrifices for the good of their children; they do without something good so as to be able to better provide for them. Soldiers will be willing to sacrifice their very lives for the good of their country. The more technical sense is used in a specifically religious context, where the worshipper once again does without something valuable – a goat, or a lamb, for example – as an expression of submission to a god, or to satisfy the demands of a god. As in the more general sense, the worshipper would expect that depriving themselves of something valuable as an act of worship would lead to greater benefits to come. To that extent, both types of sacrifice have much in common. The difference lies in the link between the sacrifice and the hoped-for benefits. It is easy to see the causal connection between a parent’s sacrificed holiday and the financing of their children’s education, or a soldier’s heroic sacrifice of his or her life and the success of their country’s campaign. But in the religious sense, the connection is not so clear. What is the god responding to when the worshipper kills a lamb? What does the god gain by it? Is it the death, the blood of the lamb, which causes the god to feel well-disposed? Why should it? Or is the lamb simply a symbol, and what the god is responding to is the recognition and devotion of the believer rather than to whatever it is that the believer has given up?

In both contexts, to make a sacrifice can sometimes seem senseless or counterproductive. Was the sacrifice of so many lives in Flanders worth it? Is that what won the war? And in the biblical tradition, we have statements such as, ‘What I want is steadfast love, not sacrifice’ (Hosea 6:6, repeated in Matthew 9:13); and the Letter to the Hebrews reminds its readers that Jesus himself said,

‘Sacrifices and offerings you have not desired, but a body you have prepared for me; in burnt offerings and sin offerings you have taken no pleasure. Then I said “See, I have come to do your will, O God”’. (Heb 10:5)

So there is a long-standing tradition in the Bible in which the pointlessness of animal sacrifice is made very clear indeed. So what are we to make of the Paschal lamb? Or the death of Jesus? Did God want his son to die?

Abraham, Isaac and Jesus

Think for a moment about the famous story of Abraham bartering with God, as one might do in an Eastern market. (Gen 18-19) How many just men must there be in Sodom for God to relent and not punish the city? Abraham uses his haggling skills, tentatively at first, to beat God’s asking price down from fifty to just ten good men. The assumption behind this story is that God is justified in punishing Sodom, but not in punishing everyone in Sodom. There is a moral issue involved: can the wicked be punished, at almost any cost to the just? Abraham does not dispute that in general terms the inhabitants of Sodom deserve all the fire and brimstone that God can throw at them. But he is sure that God sees the general moral point: and indeed God’s final answer is that the innocent should not suffer in the process of God’s punishing the guilty.

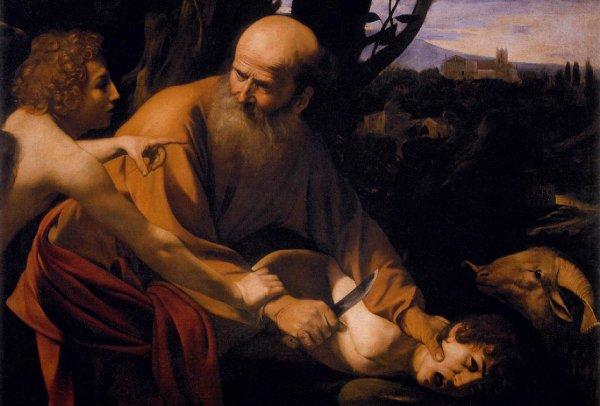

What, then, are we to make of the story, just three chapters later in Genesis 22, in which God commands Abraham to sacrifice Isaac? There is a brutal reading of this story, in which it might appear that the very God whose sense of justice was evident in the story of Sodom is now behaving outrageously to both Abraham and Isaac, asking Abraham to sacrifice his own innocent son. What kind of God could possibly demand such a morally outrageous thing?

But perhaps the story should be read quite differently; unlike the Sodom story, the story of Abraham and Isaac is not trying to make a moral point at all. A good parallel would be the story of Job. Satan claimed that Job was faithful to God only because God had given him a very good life –wife, children and riches. So God allows Satan to put Job’s fidelity to the test. And, humbly but triumphantly, Job’s faith in God never faltered despite the disasters by which Satan tempted him and the convictions of his friends that he, or his children or someone, must have offended God and Job was being punished for it; Job did not claim to understand what God was doing, he simply trusted. The book of Job is not about ethics, in the way in which the old story about Sodom was: it is about the nature of faith and what faith should be based upon. The conclusion is that there comes a point at which understanding has to be replaced by sheer trust.

The story of Abraham and Isaac can be read in the same way. In the story as it is in Genesis, Abraham knows what he has been asked to do, but Isaac does not. But in Jewish tradition there is a variant version of the story, in which it is Isaac who knows what is to happen, and Abraham who does not ; and still a third version, where both Isaac and Abraham know what is being asked of them. In all three versions the story illustrates how being tested brought the very best out of Abraham and Isaac. They remembered that God had promised to multiply the children of Isaac throughout the whole world; and, despite the apparently awful fate which awaited Isaac, they trusted in God. The lamb which God provided to be slain instead of Isaac was the sign of God’s fidelity.

In later Jewish tradition, the lamb which God provided to be sacrificed became a symbol of Isaac himself; and there is evidence that at the time of Jesus, some Jews celebrated the Passover meal in such a way that the Paschal lamb was explicitly declared to be a symbol for the body of Isaac. The lamb which Abraham killed in place of Isaac on Mount Moriah (where the Jews were one day to build the Temple) was not seen as a sacrifice of atonement, but, like the Paschal lamb, as a symbol of God’s fidelity.

Jesus is described as the Lamb of God, perhaps in a parallel to the lamb in the Isaac story and to the Passover lamb. In the garden of Gethsemane, Jesus’s trust in God was tested and was not found wanting; God’s angel comforted him. So great was his faith that even at the hour of his death, when he felt forsaken by God, Jesus quoted psalm 22 which is an act of total trust. Though the psalm begins with an almost despairing wretchedness – ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’ – it ends with confidence: ‘…future generations will be told about the Lord and proclaim his deliverance to a people yet unborn, saying that he has done it.’ So in Luke’s Gospel, when his death was imminent, Jesus could comfort the good thief in just that way: ‘Today you shall be with me in paradise’; and in his own final prayer, Jesus said, ‘Father, into thy hands I commend my spirit.’ Christians believe that his trust in the fidelity of God was total, and was vindicated in his resurrection.

One major strand in Christian theology tried to explain the value of the death of Jesus in terms of a ransom paid by Jesus to the devil in exchange for the freedom of us sinners; or to say that only the supreme value of the blood of God’s son was sufficient recompense to God for our sins. The parallel with the story of Isaac was forgotten. St Anselm and then Abelard pointed out how it was totally unsuitable to see the value of what Jesus did in terms of ransom or atonement; they questioned whether ‘sacrifice’ in that sense was the best way to think of what Jesus’s death should mean for us. Perhaps we can all benefit from the thought that it is not sacrifice in that sense that God is interested in, but steadfast love, come what may.

Jesus in the Eucharist

So, if we can see the Paschal lamb not as a sacrifice offering, but as a symbol of the deliverance of God’s people from Egypt when all seemed lost, we can perhaps look differently at Jesus’s Last Supper. At the supper, Jesus tried to prepare his disciples for the test to come. Just as the Paschal lamb was seen by some Jews as a symbol of Isaac, and hence as a sign of God’s fidelity to his side of the Covenant, so, we may suppose, Jesus took bread as a symbol of himself given trustingly to God; and, in parallel to the reference to the lamb as the body of Isaac, in the Passover ritual, Jesus said ‘This is my body, which will be given up for you.’ And at the end of the meal, in a further effort to help the disciples to understand, he asked them to see the shedding of his blood as the sign of the new covenant with the God who spared his people in Egypt when they marked their doors with the blood of the Passover lamb. And just as Isaac did not die on Mount Moriah, despite what seemed about to be his end, so, in Christian belief Jesus’s death on the cross was not his end: he rose from the dead. The disciples needed to recognise, and be themselves strengthened by, that total trust. Subsequent Christians, too, needed to see themselves in this light. The Emmaus story at the end of Luke’s Gospel was written to make precisely this point. Luke describes two very disillusioned disciples who finally learned how to understand the scriptures – perhaps including the very passages about Abraham and Isaac we have been considering – and so learned to recognise Christ in the breaking of bread, who, at that moment, was no longer visible. (Lk 24:13-25)

When Christians at the Eucharist say ‘Do this in memory of me’, the phrase is often understood as Jesus exhorting us not to forget all that he has done for us. But another interpretation is that Jesus meant: ‘Do this so that God may remember me’. So in one of the Eucharistic prayers, Catholics also ask God to remember what Jesus did: ‘look upon this sacrifice and see the victim whose death has reconciled us to yourself.’ We trustingly ask our Father to look upon us, as we try to follow the example of Jesus’s total trust in God. And so, in our Eucharist, we too pray to God that just as he was faithful to his Covenant and raised Jesus from the dead, so he would be faithful to us when we, his disciples, celebrate the Eucharist in Jesus’s name.

Gerard J. Hughes SJ is a tutor in philosophy at Campion Hall, Oxford. He is the author of Aristotle on Ethics, Is God to Blame? and Fidelity without Fundamentalism (DLT, 2010).