Director: Steven Spielberg

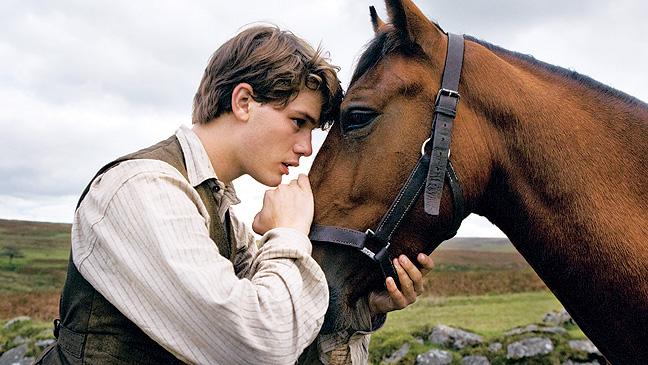

Starring: Jeremy Irvine, Emily Watson, David Thewlis

UK Release date: 13 January 2012

Certificate: 12A (146 mins)

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a story that began life as a children’s novel, War Horse fights shy of engaging with the horrors of war, death and destruction. Meshing together a series of smaller tales that reflect the huge changes wrought across Europe by the First World War, it weaves a single, sentimental narrative around the adventures of one horse and his boy.

The film’s attempt at a moral comment on the role of animals at war is left in the background: even the dramatic chase across the bloody, muddy trenches has only ‘moderate violence’. Instead, War Horse follows a simple line, emphasising the emotional connection between the heroic horse and his original, west-country, farm-boy owner. If the end is more sentimental than poignant – they are reunited and come back to a Devon that is ravishingly filmed – it matches the atmosphere of the entire movie. There are many deaths, but few are shown and most implied.

Although there are scenes that emphasise the way that animals are mistreated in battle – the German army seems to lack any empathy, while the British involve them in noble yet doomed charges – the war horse is a vehicle connecting a series of vignettes. The first story, which sets up the overall arc, is set in a pre-war Devon, where class conflict is embodied in the horse and the boy’s plucky reclamation of a stony field. The action moves to the British army, where the horse is parted from his owner and leads a charge into enemy territory: captured by the Germans, the horse is involved in a brother’s attempt to rescue his younger sibling from the front-line. These switches continue until the final, inevitable reunion.

Each of these episodes introduce characters who are sketched and swiftly dispatched. The horse, never a gushingly expressive animal, is the only real constant. Even the boy disappears for a large section of the film. Because of this, there is no sense of development or sympathy. The humans are merely stereotypes, signalling the extent of the war’s destruction but adding little drama.

In the absence of a central protagonist, Spielberg uses the scenery to build the atmosphere. Devon is recognisable and appropriately lush. The trenches are a hell of barbed wire, deep mud and floating gas clouds. A Belgian windmill becomes an oasis of calm merely a hill-rise away from the advancing armies. Every scene has picture book clarity, without becoming chilling or vicious. It’s here, rather than in the plot, that the idea of war’s horror is most immediately expressed.

Although there is a superficial charm in many of the characters – the boy, Albert (Jeremy Irvine) maintains a sweet disposition even in the trenches and Niels Arestrup’s grandfather evokes a moving relationship with his ill granddaughter – they lack enough depth to carry the story. At times, there is an uncomfortable juxtaposition between the fairy-tale magic of the narrative arc and the grim reality of history. When two soldiers on opposing sides meet in the trenches to help out ‘this wonderful horse’, it might echo the famous Christmas truce where the Germans and English played football, but it does little to reveal more about the conflict or the people involved.

Yet, as a children’s film, it is not overwhelmed by schmaltz and makes a brave attempt to at least introduce the nature of war as something un-heroic and brutal. Perhaps the main problem lies in using an animal as the central character. Unable to express anything of the experiences, mute and apparently unperturbed by the explosions and deaths around it, it leaves a gap at the centre of the film. Unsurprisingly, the theatre version chose to use a puppet over a real animal: and that production remains one of the UK’s most popular shows.

Gareth Vile

![]() Visit this film's official web site

Visit this film's official web site