Director: Claire Denis

Starring: Alex Descas, Mati Diop, Nicole Dogue, Grégoire Colin

UK Release date: 9 July 2009

Certificate: 12A (101 mins)

There’s a lot more to francophone cinema than what we get to see in the UK. Take, for example, the recent Belgian biopic Soeur Sourire (‘Sister Smile’) about the Dominican nun Jeanne Dekkers (who is usually referred to in English as The Singing Nun). She had fleeting but blazing international success in the 1960s with her folk-number ‘Dominique.’[1] The song was so ubiquitous at a certain point in the sixties that its popularity led to the coinage of ‘niquer,’ derived from the chorus (in which ‘Dominique’ is rendered ‘Dominique-inquer-nique’). ‘Niquer’ apparently came to signify a certain type of sexual activity – though I should point out that my source for this is an un-referenced assertion on the French pages of Wikipedia. All of this – the Belgianness, the nun, the song, the guitar, the inevitable innuendo – would be simply amusing were it not for the joint suicide of Jeanne Dekkers and her lover, Annie Pécher, in 1985.

The point of this otherwise apparently irrelevant digression is to suggest that our image of what is ‘francophone’ or ‘French’ or ‘francophone cinema’ is heavily mediated by economic and cultural forces outside our control – in this case the distribution companies. Somebody decides which ‘French’ films we will get to see, no doubt based on what they think we will pay to see, a decision predicated on what everyone on this side of the Channel thinks ‘French’ films are about. In consequence, this reviewer will be very surprised if Soeur Sourire is ever distributed in the UK, even on a limited release – though it will probably get a screening at the London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival.

So what do you expect from ‘French film’? What do you expect from a film about a young black student living in the Parisian suburbs? Put those elements together, and no doubt images of gritty resistance, rap, tagging and possibly even barricades spring to mind. And these assumptions – prejudices, one might call them – are actively exploited by those distributing 35 Shots of Rum in the UK. In the advertisements for the film, much is made of what is actually merely a fleeting subtext: an angry young man increasingly drawn to violent rebellion, who is shown citing Martinican psychologist and revolutionary Frantz Fanon in a university class.

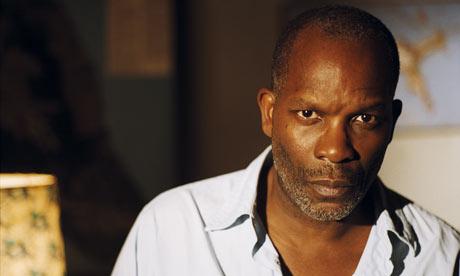

The class is an anthropology seminar attended by Jo. She lives with her father, Lionel, a train driver; he is quiet, detached and apparently content, though marked by the shadows of loss. Father and daughter love each other – his wife, her mother, is dead. Jo has a substitute mother in the shape of Gabrielle, who lives in the same building and is also attracted to Lionel. Jo is pursued by Noé, the boy upstairs (quiet, depressive, un-political) and one of the more radical ‘types’ at college. Lionel’s friend René is about to retire, and can’t really cope with the idea.

That’s it. No revolution, no burning cars, no racist police. The ‘Frenchness’ here is closer to that which we saw last year in the very bourgeois and very white Summer Hours than that portrayed in La Haine or Diva – it’s the France of the endless talk-shows and the café culture out of which existentialism was born. And everyone (apart from a single, silent, extra in a café, late at night) is black.

So one of the things that strikes this reviewer as interesting about 35 Shots of Rum, is that it is almost not about ethnicity: it’s about people living their lives, who happen to be black as well as French. And there’s something refreshing about that.

It’s also a lovely film: director Claire Denis offers us an older woman’s gaze on a younger one’s body, letting the camera linger on Jo’s – sensitively played by newcomer Mati Diop – skin, on her hair, her defensively baggy clothes, and finally, her sharply tailored suit in which she leaves her father’s home in the closing scenes of the piece.

The central story, then, is a sensitive and intimate portrayal of late adolescence, and a determinedly loving study of the complexity of a father-daughter relationship (and other family knots and messes, besides). Around this core are woven the stories of Lionel’s friendships (René’s depression, Gabrielle’s unrequited desire), and the ever-present metaphor of the RER (the French suburban railway system), which seems to stand for everything about life: all is movement and change, and yet all is ossified and static at the same time. Denis seems to be suggesting that existence and family relationships are like a railway system, set in iron and concrete, yet somehow also always moving somewhere.

And if you are still interested in finding out what the Singing Nun’s hit sounded like, the disco video remix – yes, that’s right, the disco remix – can be viewed here. But I warn you, it’s one of those tunes you won’t be able to get out of your head for the whole day.

Ambrose Hogan

Dominique-nique-nique s'en allait tout simplement,

Routier pauvre et chantant.

En tous chemins, en tous lieux, il ne parl'que du Bon Dieu,

Il ne parl'que du Bon Dieu.

(Dominic-ineeque-ineeque in every thing simplicity,

Poor singing mendicant,

On all journeys, in all ways, he spoke of nothing but the goodness of God

He spoke of nothing but the goodness of God.)