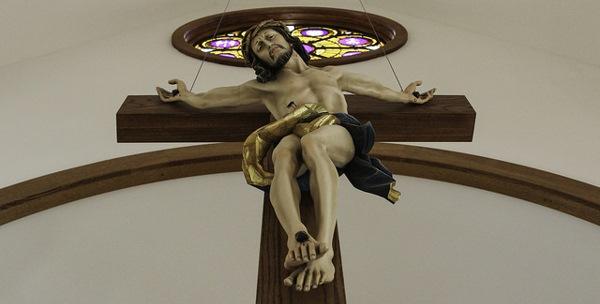

14 September is the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, a celebration whose significance can be discovered through careful consideration of the readings chosen for the day. Fr Harry Elias SJ helps us to see the cross as holy and understand how Jesus was ‘exalted’ in the crucifixion.

The feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross on 14 September commemorates two historical events: the discovery in 326 of what was regarded as the true Cross, under the temple of Venus in Jerusalem, by Saint Helena, the mother of the Emperor Constantine; and the dedication in 335 of the basilica and shrine built on the site.

However, a real understanding of this feast is not to be found in the historical descriptions of those events and what followed them. Instead, one has to go to Scripture and look especially at John’s Gospel and the way in which it treats the first reading that we hear on the feast, the story of Moses and the bronze serpent (Numbers 21:4-9). In that story, Moses is commanded by the Lord to set up a bronze fiery serpent on a pole, so that whenever a person was bitten by a serpent, that person would look at the bronze serpent and live. In the feast’s gospel reading (John 3:13-17), Jesus tells Nicodemus that he, as Son of Man, must be ‘lifted up’, as was the serpent, so that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.

The first meaning of the Greek word that translates here as ‘lift up’ is ‘exalt’, a term which is associated more readily with the resurrection than the crucifixion. However, by its association with the incident of the bronze serpent, John seems to have in mind both the setting up of Jesus on the cross, the crucifixion, as well as his exaltation in the awesome splendour of resurrection.

Matthew, Mark and Luke all tell of Jesus’s agony in the garden of Gethsemane, asking the Father to remove the cup of suffering, and then of his anguish on the cross – an all-too-human Jesus. Perhaps, even after giving himself over as the sacrifice of the new covenant at the Last Supper, Jesus hoped against hope that he would be spared. This is quite like our own obedience in accepting something painful and yet hoping for some miracle. The words of Jesus’s cry on the cross: ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’, are from Psalm 22, a psalm of lament. The Hebrew bible is strewn with prayers of lament, some individual, some collective. Quite a number end with expressions of confidence, as does Psalm 22 itself. Although lamenting is loosely seen as complaining, the biblical word for complaining is ‘murmuring’, equivalent to ‘speaking out against’, as the Israelites do in the first reading when they feel worn out in their journey through the desert. Lamentation is prayer in times of grief; murmuring is a temptation that we pray to avoid.

John differs from the other evangelists in his reluctance to see the crucifixion as a humiliation. He omits the agonised plea in Gethsemane and the cry of desolation on the cross. The Jesus of John’s gospel says: ‘Now is my soul troubled. And what should I say – “Father, save me from this hour”? No, it is for this reason that I have come to this hour’ (John 12:27). For John, the incarnation was a manifestation of divine glory (John 1:14), and the cross instrumental for its completion. This perspective – of seeing past the reality of the suffering to its significance as the means of exaltation, and in that way seeing the cross as holy – can be pastorally helpful. It infuses hope even in our prayers of lament, a hope when all seems lost.

For Paul, the essence of the gospel was Christ crucified: ‘For I decided to know nothing among you except Jesus Christ and him crucified’ (1 Corinthians 2:2). In the second reading of this feast day (Philippians 2:6-11), Paul sees the cross as an instrument of exaltation, through which God gives Jesus the name that is above every name: Jesus can now be acknowledged by all as Lord. Yet, in contrast to John, the cross itself is humiliation and the incarnation a voluntary self-emptying; for Paul, neither are manifestations of glory in themselves.

In his exaltation, Jesus is Lord with a new bodily identity, no longer with its exclusively Jewish traits, but one that has become lovingly inclusive of all, and covenanted to all. To be in (the risen) Christ, is to begin acquiring a new identity which is likewise inclusive of all, even one’s enemy: ‘There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus’ (Galatians 3:28). This new creation is in the process of emerging. Paul compares this process to the pains of childbirth (Romans 8:22). All the same, our new identity preserves our innermost character, both spiritually and physically, as did Jesus’s (see especially the resurrection appearances in chapters 20 and 21 of John’s Gospel).

Our new selves ‘in Christ’ live with God’s life, eternal life. ‘I am the resurrection and the life’, Jesus tells Martha, the sister of Lazarus. Resurrection life, while preserving identity, is ever faithfully and lovingly new. At present, we are likened to a grain of wheat that has to die in order to be fruitful (John 12:24). How it is in our risen bodies, when ‘death has been swallowed up in victory’ (1 Corinthians 15:54), we have yet to discover; how it is eternally present in God’s life, we cannot understand.

Exaltation in John’s Gospel, as we are told on this feast, is of Jesus as Son of Man: ‘No one has ascended into heaven except the one who has descended from heaven, the Son of Man’ (John 3:13). The Son of Man is the intermediary, the mediator between God and man, the ladder connecting heaven and earth (cf. John 1:51, a reference to the dream of Jacob at Bethel in Genesis 28:12-17). Jesus intercedes and comforts us with hope especially in times of trial and desperate need, when we are sorely tempted to ‘murmur’, to speak against God as the Israelites did in the first reading.

In those who accept and endure in faith their suffering, especially in those who risk their lives and are victimised for seeking justice, that new identity is emerging which makes them Jesus’s brothers and sisters (see Mark 3:34). In baptism, Christians declare their willingness to die with Christ so as to live with their new, risen identity (Romans 6:4).It is the beginning of their own exaltation, their own new, inclusive identity, emboldening them to go out from their doors ‘locked for fear’ (John 20:19) and, as mediators in Christ, convey by prayer, word and deed the forgiveness, reconciliation and hope they experience in their own sufferings, and the resulting joy and peace.

Harry Elias SJ assists in the Hurtado Jesuit Centre in Wapping, East London.