‘Mary attests that the mercy of the Son of God knows no bounds and extends to everyone, without exception,’ wrote Pope Francis when he announced the Year of Mercy. As the Jubilee Year draws to a close, Teresa White FCJ reflects on how Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins articulated the way in which Mary’s own merciful gaze falls upon us.

For the most part, Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poems have short and expressive titles: ‘Hurrahing in Harvest’, or ‘The Windhover’, or ‘The Lantern out of Doors’, for example. Such titles have an immediacy that invites the reader to hear what the poet hears, to share his contemplative gaze, to ponder his words. But take ‘The Blessed Virgin compared to the Air we Breathe’ – that title is different. It has a less direct appeal, is long-winded, and seems almost contrived. Indeed, as we read that title, what are we to think? Is this a poem or a theological treatise?

Until relatively recently, in religious houses, communities marked the liturgical seasons with a variety of devotional practices – perhaps some still do – and it was common for individual members to compose verses and produce paintings and drawings in honour of the saints and in celebration of feasts of the Church. From my own experience, I know that Mary was a special favourite, and the whole of the month of May, as well as the many named feasts of Our Lady, offered a fruitful source of inspiration for literary and artistic talent. Who could doubt that Hopkins’ ‘May Magnificat’ was written for just such a purpose? However, when the Jesuits at Stonyhurst, where he lived in 1883, read ‘The Blessed Virgin compared to the Air we Breathe’, also written for the month of May, they may have got more than they bargained for! Filled with profound thoughts, creative syntax and wonderfully original vocabulary, the poem might have been thought unduly long and convoluted. With its rhythmical three-foot couplets and triplets, it is relatively easy to read aloud, but its content is not always straightforward. Hopkins himself was dissatisfied with it, acknowledging in a letter to Robert Bridges that ‘… the highest subjects are not those on which it is easy to reach one’s highest’.

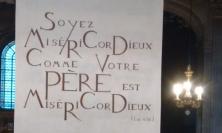

Yet it must be said that ‘The Blessed Virgin compared to the Air we Breathe’ is particularly relevant during this Jubilee Year of Mercy, and certainly bears re-visiting, for mercy is its principal theme. It is well known that the gods of old were feared rather than loved, and that people sought to allay the anger, vengefulness and destruction attributed to them by offering sacrifices and prayers, by obeying ‘commandments’ and leading a ‘good’ life. In the Hebrew Scriptures, concepts like hesed (kindness) and emeth (faithfulness) point to a gradual unfolding in Judaism of the notion of a more benevolent God. But it was with the advent of Christianity that mercy, God’s love living in us, became the central aspiration of religion in the Western world. Paul, in his letter to Titus, says this clearly when he writes of ‘the kindness and love of God’, who saved us ‘for no reason except his own compassion’ (3: 4). It is mercy that leads to true compassion, for the one who is merciful knows what it feels like to walk in the shoes of the oppressed and the vulnerable, to walk hand-in-hand with them. To be merciful means to bless, to shelter, to heal, to forgive. It communicates a caring presence, expresses a loving humanity. One of the most popular depictions of Mary in Christian art is as Mother of Mercy: we see her, tender, compassionate, sheltering people under her outspread cloak. In Hopkins’ words, ‘She, wild web, wondrous robe, /Mantles the guilty globe’. She is the one who surrounds us all with the ‘air’ of mercy: ‘… we are wound/ With mercy round and round/ As if with air’.

In our time, living as we do amid global terrorism, conflict, crushing poverty and ecological degradation, there could hardly be a more comforting message. Mary is the one whom God ‘has let dispense … his providence’, his mercy, and she does this through her loving concern for the whole of creation. Mary’s is a ‘high motherhood’, for from the beginnings of Christianity, the cosmic role of Christ, which Hopkins hints at in the poem, was believed to have been shared by Mary, in whom the Word of God took human form. Paul’s portrait of Christ as ‘the image of the unseen God, and ‘the first-born of all creation’ presents him as one with the Creator God: ‘… in him were created all things in heaven and on earth: everything visible and everything invisible’ (Colossians 1: 15, 16). In popular piety, Mary, as the female agent of the new creation, participated in the protection and nurture of the universe and of every living thing in it. Through her, as Hopkins put it, we see ‘God’s infinity/ Dwindled to infancy’. Mary brings God into our orbit; she is the ‘world-mothering air’ that surrounds us. Through her, in the words of another poet, the great God who is hidden from our sight in ‘… the loneliness … the unpeopled skies … the gigantic solitude of the Cosmos’ (Kathleen Raine, ‘Northumbrian Sequence IV’) entered our world, and was brought close to us. Through Mary, femininity is in some sense divinised and motherhood raised to the same level as the fatherhood of God. Hopkins says that as a mother, she makes her Son ‘the daystar/ Much dearer to mankind’. The opening verses of the Letter to the Hebrews speak of Christ as ‘…the radiant light of God’s glory … sustaining the universe by his powerful command’. But that ‘glory bare’ would blind us, so Mary’s hand ‘sifts’ the radiant light ‘to suit our sight’; and she does this because of her motherly sensitivity to our needs.

A new edition of the long text of the ‘Revelations of Divine Love’ of Julian of Norwich appeared in 1877. There is no record of Hopkins having read it, but his portrayal of Mary in this poem has much in common with Julian’s vision of the ‘motherhood’ of God: ’I saw that for us he is everything that is good, comforting and helpful; he is our clothing, who, for love, wraps us up, holds us close; he entirely encloses us for tender love, so that he may never leave us, since he is the source of all good things for us, as I understand it’ (Revelations 5). Both Julian and Hopkins recognised that in the sphere of faith, symbols carry a sacred, mystical quality, and both used the symbol of motherhood in their approach to the ultimate mystery that is God. Hopkins, in ‘The Blessed Virgin compared to the Air we Breathe’, sees Mary as a context for the poetic expression of this mystery, uniting as she does the human and the Divine. And she enfolds in God’s mercy the whole of creation.

Sister Teresa White belongs to the Faithful Companions of Jesus. A former teacher, she spent many years in the ministry of spirituality at Katherine House, a retreat and conference centre run by her congregation in Salford.