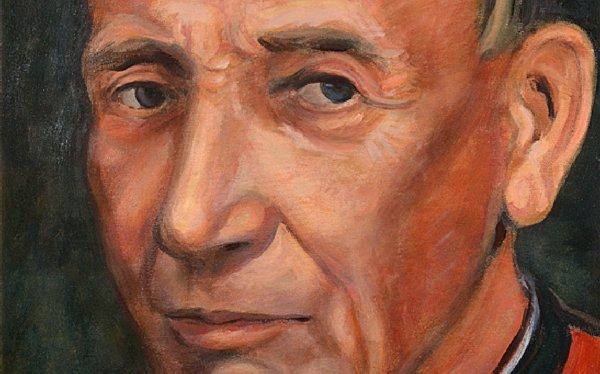

In this month’s text from the Jesuits in Britain’s 2014 calendar, Norman Tanner SJ reflects on the life of Augustin Bea. The German cardinal is one of twelve remarkable Jesuits who feature in the special calendar, which commemorates the 200th anniversary of the restoration of the Society of Jesus.

Life

Born in 1881 in Riedböhringen, a village within the Black Forest in Bavaria, Augustin was the only child of Karl and Maria Bea. After finishing school, he spent two years studying theology at the University of Freiburg. Then, aged 21, he embarked upon his new life as a Jesuit, entering the novitiate of the South German Province. He followed the normal studies of philosophy and theology and was ordained priest in 1912. Soon afterwards he pursued specialised studies in ancient Near Eastern philology at the University of Berlin and from 1917 to 1921 he taught Old Testament at the theologate for German Jesuits, which was then situated at Valkenburg in Holland, as well as acting as their Prefect of Studies.

Major new assignments followed. He was appointed Provincial (head) of the Bavarian Province, and Visitor (inspector) of the Japanese Mission, of the Society of Jesus. Then in 1924, he was appointed Professor at the Biblical Institute in Rome, where he remained for more than 30 years, serving as Rector from 1930 to 1949. Many other duties and responsibilities came during this time: work directly for the papacy on the Pontifical Biblical Commission and in the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (then called Holy Office); chairman of the commission for the revision of the Latin psalter; and confessor to Pope Pius XII from 1945 until the pope’s death in 1958.

Meanwhile, he was publishing numerous books and articles, steering a creative middle course in Biblical studies between fundamentalism and exaggerated relativism. In 1935, with the approval of Pope Pius XI, he participated in the Old Testament congress of Protestant scholars at Göttingen in Germany, providing an encouragement to ecumenical cooperation in Biblical studies. Important, too, was his contribution to Pope Pius XII’s encyclical on the interpretation of Scripture, Divino afflante Spiritu (the first words in the Latin text), published in 1941, which gave further encouragement to responsible Catholic Biblical scholarship.

The third and final stage of Bea’s life began in 1959. In that year, the newly elected Pope John XXIII made him cardinal and shortly afterwards appointed him Prefect (head) of the Vatican’s newly established Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity, a post which he held for the rest of his life. He played an important role in the Second Vatican Council (1962-5), principally regarding its decree on Scripture, Dei Verbum. The document has had a major impact ever since, encouraging Christians and indeed all people to draw from the riches of Scripture in their life and prayer as well as through study. Bea’s influence was more on the preparation and writing of Dei Verbum than on its reception, for he died in Rome only three years after the end of the council at the venerable age of 87.

Reflections

Bea’s life was long and full. I am 70 years old, gradually approaching his lifespan. My reflections, therefore, are somewhat personal. They are divided into four topics.

1. Unforeseeable. This is an obvious point but worth making at the start. We are liable to read life-stories too readily with their completion in mind, almost as if the end result was inevitable. Maybe this is known beforehand to God, but not to us, nor the individual! There is particular edge for Augustin Bea in this respect, for as a German he survived – far from inevitably – the horrors of two World Wars.

2. Nationality. Jesus was a Jew to his fingertips, so to speak. Nationality is very important even in our somewhat supra-national age, when crossing frontiers and living in other countries is common. Bea had the fine qualities of his nation.

As an Englishman, Germany featured prominently in my childhood. I was born during the Second World War. My father was in the RAF (Royal Air Force). For him and my mother, as well as for their parents and relatives, the two Wars loomed large and they knew the horrors. As schoolboys, however, perhaps in reaction to our parents, we were morbidly fascinated by the exploits of the German army and had much respect for the people.

The links between our two nations, indeed, go much deeper. England, land of the Angles, the adjective Anglo-Saxon, and the English language reveal our roots in the German tribes who came to this country in the sixth century. Boniface (675-754), English monk and great missionary to Germany, knew well these intimate ties. In a famous letter to the English people, he appealed for their prayers and help in the conversion of those who ‘are of one blood and bone with you’. Such affinity is in my bones too, therefore some closeness to Cardinal Bea.

3. God’s will and our cooperation. Bea’s long life reveals the intimate yet complex relationship between God’s will and our cooperation. Here we can only scratch the surface: the full truth is known only to God and partly to Augustin. We may see this cooperation first through the responsible and pious upbringing given to him by his parents. Then the young Augustin takes the initiative, responding to God’s will and conscious of his own talents: first through two years study of theology at Freiburg, then applying for entry into the Jesuit novitiate.

Having been incorporated into the Society of Jesus through the vows which he took at the end of the two years’ novitiate, Bea was now subject to a further consideration in his cooperation with God: obedience to the Jesuit Rule and the directives of his Superiors. His long Jesuit life and ministry indicate abundantly this fruitful cooperation with God’s will as well as with the directives of his Jesuit superiors and of other authorities within the Church, notably successive popes, while, at the same time, he remained conscious of his own gifts and faithful to his instincts. A fine blend of creative fidelity!

4. Work for the papacy. One of the final vows which Bea took, together with other Jesuits soon after their ordination as priests, was fidelity to the papacy. His life, outlined above, shows how prominently this vow featured: his long apostolate at the Biblical Institute, which came directly under papal authority; the commissions given to him by Popes Pius XII, John XXIII and Paul VI, including assignments during the Second Vatican Council. But here too his fidelity was creative. In his early years as a Jesuit he lived through the Modernist crisis, when Pope Pius X warned against interpreting the Bible too liberally; many bishops at Vatican II followed a similar line, hostile to Bea’s greater openness. Work for the papacy surely brought him suffering and anxiety, as well as consolation.

Academic apostolate

Let me add some reflections on Augustin Bea as scholar. Study and scholarship were central features in his life and for me, with some experience of teaching and writing, these aspects are of particular interest.

1. Many roles. The dictum for teachers at Oxford University, during my years as lecturer there, said there were three tasks and you had to engage in any two of them: teaching, writing and administration. Bea is remarkable in that he performed notably in all three and at the highest level in academic administration. He published books and articles over a long period of time and, as mentioned, he taught at both Valkenburg in Holland and the Biblical Institute in Rome. His unstinting labours in administration and organisation, which included much help and encouragement given to others, have also been outlined: his administrative duties at Valkenburg and the Biblical Institute, his involvement in papal commissions, and his labours at Vatican II. Remarkable, too, is the fruitfulness of his work. Vatican II continues to inspire: successive popes have resolutely promoted Biblical studies and the importance of Scripture in Christian living; the Biblical Institute in Rome continues to flourish and to form teachers and pastors in the Church.

2. German scholarship. Throughout Bea’s life, German scholarship was held in high esteem regarding Biblical studies, as well as many other subjects. Protestants and other scholars from Germany, more than Catholics, had brought a new level of craft to Biblical scholarship in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Bea entered into this tradition and helped the Catholic Church to welcome its strengths as well as to be aware of its limits. Excessive caution regarding Biblical scholarship, culminating in the Modernist crisis of the early 20th century, was transformed by the more positive approach of Pope Pius XII and especially through Vatican II’s document on Scripture, Dei Verbum. Bea was close to Pius XII and played a major role in Dei Verbum.

3. Wider world. Bea surely benefited from his Catholic roots in Germany, yet he moved readily onto the wider stage. He left his native country and moved to Rome. He looked beyond Catholic scholarship to appreciate the insights of Protestant and secular scholars. Indeed he became a world-renowned figure. Surely he was much helped by his Jesuit vocation, which required mobility and constant search for the greater good. But without his own cooperation and fidelity, the good results would not have been realised.

Conclusion

Let me conclude with gratitude. Augustin Bea provides encouragement on many fronts. His life and example urge us to make best use of the talents given to us and of the opportunities that life affords. At the same time, we are invited to be attentive to others constructively and sensibly: to our brothers and sisters in Christ, in a variety of ways, and above all to God. Finally, for those of us involved more full-time in academic work, the cardinal provides added encouragement and inspiration.

Norman Tanner SJ

To purchase a copy of the 2014 calendar, and to find out more about Cardinal Bea and the other Jesuits featured, please visit: www.jesuit.org.uk/calendar2014