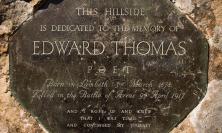

On 11 November each year, we observe Remembrance Day and honour the members of the armed forces who have lost their lives at war. Can faith help us to make sense of the reality and horror of war? Roger Dawson SJ looks to the theology of Johann Baptist Metz, who had his own ‘dangerous memories’ of war, to ask how we can speak about God in a world of conflict.

Towards the end of the Second World War, a 16-year-old boy was conscripted into the German Army and was sent to the front near the Rhine in an infantry company of youths of a similar age. One evening, he was sent with a message to Battalion headquarters; he returned the next morning to find that his company of over a hundred had been overrun in the night by an Allied bomber attack and an armoured assault. He said, ‘I could see now only dead and empty faces, where the day before I had shared childhood fears and youthful laughter. I remember nothing but a wordless cry’. This man was Johann Baptist Metz, who later became a priest and one of the great 20th century theologians. He remained haunted by the memory and by this question: ‘What would happen if one took this not to the psychologist, but into the Church … and if one would not allow oneself to be talked out of such memories even by theology?’ What if we wanted to keep faith with such memories – ‘dangerous memories’, he calls them – and with them speak about God?

On Remembrance Day we remember the war dead of two world wars and many other conflicts, including those who have died in Iraq and Afghanistan. If we are to do justice to these ‘dangerous memories’, as Christians we cannot gloss over this with tales of heroism and noble sacrifice, though there is much of that. The fact is that war and violence can never be willed by God; war has no place in the Kingdom of God and is not the way to the Kingdom of God. Even Just War theory gives the criteria to discern when war is the least bad option, rather than a good in itself.

So what does our faith have to say to us about this? What if we use such facts – and memories – to speak about God? We may end up with more questions than answers, but central to our faith as Christians is that we are people of the resurrection. We are not limited by a horizon of death and by a few memories of us held by those who remain behind, but we believe in life beyond this, in union with God. That is the basis of our hope.

The point is that the resurrection of Jesus tells us that death and evil and war will not have the last word. The resurrection was not a post-script to Jesus’s life, but the guarantee of the gospel: that love is more powerful than death; that good ultimately is more powerful than evil; and that God is the God of the living. The resurrection is the revelation of that truth, and our faith tells us that we can be part of it, too: God’s love and life is more powerful than death; and our life and love will not be crushed, even by bombers and armoured squadrons.

None of this makes tragedy, loss and suffering alright; it does not silence Metz’s ‘wordless cry’, nor does it sanitise or make safe his ‘dangerous memories’. Such experiences remain an evil, and we have to live out our faith not just with the best, but with the worst of humanity – the killing fields of Cambodia, the genocides of Rwanda, the battlefields of Afghanistan, the carnage of Syria, the shadows of Auschwitz. But memory is part of our faith. For Catholics, tradition is very important, and we cannot have tradition without memory. What keeps us going through tough times is the memory of what God has done for us, the love that we have seen made incarnate in our family and friends and through the sacramental life of the Church, and the belief – or hope – that we will get through this. Without these memories, faith weakens and our hope fails.

Memory is also central to the Mass. ‘Eucharist’ means ‘thanksgiving’, which is why at the start of Mass it is important to call to mind (remember) not just our sins, but that for which we are grateful. And all of the Eucharistic prayers are peppered with ‘remember’, ‘in memory’, ‘recall’, ‘in remembrance’. ‘ Anamnesis’ is the Greek word meaning ‘reminiscence’ or ‘memorial sacrifice’, and refers to both the memorial character of the Eucharist, and the Passion, Resurrection and Ascension of Christ. It has its origin in Jesus's words at the Last Supper, ‘Do this in memory of me’ (Luke 22:19, 1 Corinthians 11:24-25). Anamnesis is also a key concept in liturgical theology – that in worship the faithful recall God's saving deeds. If we take this seriously, then we are confronted with not just the memory of Jesus with his disciples at the last supper, but the ‘dangerous memory’ of his suffering and experience of injustice at the hands of humans. It is no coincidence that the only human mentioned in the Creed apart from the Virgin Mary is Pontius Pilate.

Johann Baptist Metz based his theology on the memories of history’s catastrophes, without which theology ‘become[s] trivial or irrelevant, and Christian faith a banalised reflection of the prevailing social consensus.’ [1] It addresses believers at those points where they and their faith are most threatened by the social and political catastrophes of history. His theology consists of a basic defence of the trustworthiness of Christian doctrine as ‘good news’ in the modern world, seeking to demonstrate the truth and transformative power of Christianity in the face of historical catastrophes and political struggle. His theological starting and centre point is anchored in history (therefore memory), in which Christian faith and life takes into account the whole of that history, especially that of its victims and fatal failures.

For Metz, Christianity’s real sense can only be revealed against the backdrop of our terrors and our anxieties. His theology is a ‘defence of hope’, requiring solidarity with and action on behalf of those who suffer and those whose hope is most endangered. This is a ‘threatened hope’, a ‘hope against all hope’[2] with a deep social and political tone, which must be accompanied by the radical action of Christian discipleship.

The core of Christian anamnesis is the story of Christ’s passion, representing the belief in God’s active presence in history and of God’s interruptive act of salvation at the end of history, when God will rescue those whom history has destroyed or overlooked, namely the defeated, the forgotten, the dead. This memoria passionis et resurrectionis Jesu Christi is also the memory of the suffering in biblical tradition, and is an ‘anticipatory memory’ (or reminder) of resurrection and eschatological hope. Christianity can then account for those who have died, or have been defeated or destroyed, and can rescue them on the basis of faith and eschatological hope that God is the God of the living and the dead.

Metz formulated his theology in the face of the memory of World War Two and the Holocaust, of which Auschwitz is the leitmotif. For him, theology’s task is not to assimilate such memories into a ‘system’, but to provide a language for them to be articulated and to irritate our modern consciousness. Memories and stories, particularly dangerous or unsettling ones such as those of Auschwitz, lead to critical questions and have the capacity to open up perspectives on our current reality. Indeed, Christian memory includes passion, suffering and victims; it becomes a ‘dangerous memory’, in that it confronts a triumphant or complacent society with the injustice and victims that that society has created. Without memory the dead and the victims are forgotten, and for the Christian there can be no real future if they have no place in it.

In 2006 Pope Benedict XVI visited Auschwitz and he said, ‘In a place like this, words fail. There is only a stupefied silence and a cry to God.’ Quite rightly he did not try to explain it or tidy it up - how could anyone ‘tidy up’ Auschwitz? These memories are dangerous (and painful) because we know that each of these dead is someone’s child, someone’s spouse, someone’s mother or father, someone’s friend. I have never forgotten two headstones in a war cemetery in Normandy. One had written on it, ‘We will never forget him. It seems so quiet now that he has gone’. On another: ‘To the world a soldier, but to us the world.’ These are the memories that are taken into every Eucharistic prayer.

Words fail us, but the Word will not. Jesus, the Word of God, the Word made flesh, was not swallowed up by our violence, our hate and our darkness. The Word will not be silenced and, if we listen, will continue to speak. And the Word promises us resurrection, union with God in heaven, where our questions will be answered. We wait for this in hope and trust, as we remember our ‘dangerous memories’ that refuse to be sanitised, and entrust to God all those who have died, along with our wordless cries. We will remember them. We will remember.

Roger Dawson SJ is Editor of Thinking Faith.

[1] Ashley, J.M., ‘Johann Baptist Metz’ in P. Scott and W. Cavanagh (eds.), Blackwell Companion to Political Theology (Blackwell, Oxford 2004), p.245.

[2] Metz, J.B., Zur Theologie der Welt (Mattias-Grunewald, Mainz 1968), pp.56-64.