‘Before we embark on this showcase of memory at this centenary of appalling violence, it is a good thing to ask: What are we about to do? What is a correct orientation to all of this?’ Nathan Koblintz uses the poetry of Edward Thomas, who wrote during, but rarely about, the First World War, to think critically about the act of remembrance. The words of an Ignatian prayer offer us a spiritual ideal for remembering the War – how does Thomas’s poetry come close to this ideal?

I have very clear memories of the First World War. Poppies, trenches, sacrifice, machine guns, aristocratic incompetence, the first lines of ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’: the images have been lined up since I was 12, supplemented here and there by a fact plucked from the hedgerows of The History Channel or one of the more serious pub quizzes. I suspect that my memories of 100 years ago are fairly representative of those of any non-specialist born in the second half of the 20th century.

Over the next four years it will be hard to avoid taking part in at least a few public remembrances of the War. You can attend concerts of sensitively selected music, switch off your lights or light candles at designated times, discuss with colleagues the contents of documentaries and dramas. It will almost be odd to commemorate the war in private. This is likely to be only the beginning – a child born in 2000 faces what is potentially a lifetime of centenaries, the beacons of 20th century history stretching out ahead of her.

It is easy to feel that these public performances of memory are asking us to subscribe to a particular brand of sentimentality, and it is tempting to respond with a humbug-cynicism.[1] The First World War clearly ‘matters’, although in a very different way than our personal life-stories matter to us. There is good historical argument for this: the great historian Eric Hobsbawm used 1914 as the signpost for the end of the ‘long 19th century’ and the beginning of the ‘short 20th century’, an economic, psychological and political pivot-point in world history that marked the end of British dominance.

The war was a turning point too, for the word ‘nostalgia’, something to which this essay will return. It is only in 1920 that the word took on its modern meaning of a ‘wistful longing for the past’[2]. That 14-year-old child who is writing letters to the Unknown Soldier in her history class is growing up in an age saturated with nostalgia: from the instant sepia of Instagram to pop culture’s quick churn of yesterday’s fashions, nostalgia is a particularly marketable form of memory. (To find out quite how addictive an act of memory it can be, watch how a few minutes turns into a few hours on Southampton University’s musical nostalgia page).

Nostalgia has its own language, its own codes: that word ‘redolent’ reeks of it. It strengthens memory’s tendency towards symbolism at the expense of detail. Instead of remembering the ‘thing as it was’ – with all the nuances, context, extraneous details – a nostalgic act of memory focusses on a few sensations: a piece of music, a type of clothing, a single event. Symbolic acts of remembrance such as those for centenaries are prone to this – symbols are powerful because they focus multiple perspectives and experiences into a single object or act, but there is always the risk that the symbol becomes more important than the reality it represents. Perhaps Catholics should know this best of all.

So before we embark on this showcase of memory at this centenary of appalling violence, it is a good thing to ask: What are we about to do? What is a correct orientation to all of this? Roger Dawson wrote in these pages on Remembrance Day last year about the spiritual necessity of ‘dangerous remembrance’ – how, if we want to draw on the strength of memory and tradition, to determine God’s hand in history, we must remember as accurately and fully as possible. This is quite a task. How are we to begin?

An answer is found in the first words of the Suscipe, one of the prayers of the Spiritual Exercises:

Take Lord, and receive all my liberty, my memory, my understanding…

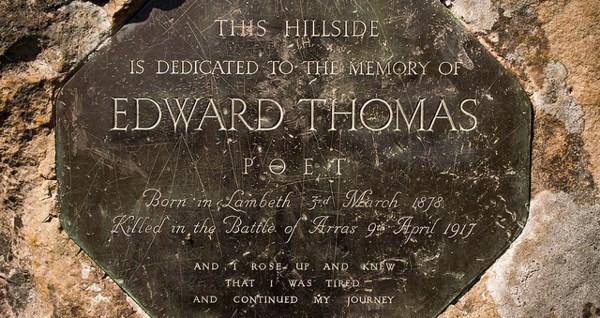

A paradox, perhaps – it demands we give up control over memory and understanding; and yet to have ‘dangerous’, not ‘nostalgic’, memories, requires an intense effort. The Suscipe presents a spiritual ideal for our remembering of the war. I would like to offer a route towards this through the companionship of a poet, Edward Thomas, who died in the battle of Arras in 1917.

*

Why poetry, and why Edward Thomas? The first is easier to answer: poetry and public remembrance have always been inextricably linked, and capturing what was lost or passing is pretty much the Primum Mobile for sitting down and writing a poem. But as well as being recruited for public statements, poetry at its best has an internal swerve towards honesty, towards nuance, towards getting the thing down right. Uncritical nostalgia in poetry is simply bad poetry.

But why Thomas? Despite the fact that his entire poetic output took place between December 1914 and January 1917 (he was already an established prose writer in his mid-thirties when he began), he is rarely read as a ‘War Poet’.[3] The years around the First World War have been bookmarked as a turning point in literary history – the canonisation and then the resultant swing away from writers like Rupert Brooke towards the ‘war realism’ of Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, followed by the modernists like Hilda Doolittle, T.S. Eliot and James Joyce. Thomas drowns in all of this categorisation: he is a poet of the English countryside and thus hard to award the badge of modernism, even though in his clarity of feeling and expression the voice of future poets like Philip Larkin is clearly distinguishable; he is a poet who volunteered and died in the war but rarely took it as a central theme.

Perhaps it is precisely this oblique yet central relationship to the war which suggests Thomas as an excellent guide to how to remember it. He was writing at a time when the rural England he adored was already under threat, and the war was simply another event which came in a succession of attacks on the livelihoods, fauna and people, that he had spent his professional career describing in prose. The war began – and ended – his poetry, but it never dominates it.

If there is a typical ‘Thomas poem’ it is one in which the poetic voice – precise, clear, unsentimental – experiences itself moving amongst the weather, the seasons, the trees and words of southern England (in particular, Kent, Hampshire and Gloucestershire):

The shell of a little snail bleached

In the grass; chip of flint, and mite

Of chalk; and the small birds’ dung

In splashes of purest white:

All the white things a man mistakes

For the earliest violets

Who seeks through Winter’s ruins

Something to pay Winter’s debts

(‘But these things also’)

You can track Thomas’s interests by listing his poem titles: ‘February Afternoon’, ‘March’, ‘March the Third’, ‘April,’ ‘May 23’, ‘July’, ‘October’, ‘November’. Rain features heavily (this is England, after all), as do traders, tramps, inn-keepers and their voices, leaves and folk-tales. His love of the countryside entwines with his love of its language (man’s only – and one-sided – gift to nature): moneywort, toadflax, harebell, meadowsweet, dog’s-mercury and missel-thrush – plant names that a hundred years ago were already fading, grow in his verses.

His poetic voice is clear, but never simplistic: his emotions receive the same critical eye that he had trained on his many walks through forests and fields:

One thing I know, that love with chance

And use and time and necessity

Will grow

(‘When first’)

I never would acknowledge my own glee

Because it was less mighty than my mind

Had dreamed of. Since I could not boast of strength

Great as I wished, weakness was all my boast.

(‘There was a time’)

The war is there, but generally in the background – the farmer in ‘As the team’s head-brass’ tells the narrator, ‘One of my mates is dead. The second day / In France they killed him.’ Thomas had the opportunity to join his friend Robert Frost in America, but after much deliberation, signed up with the Artists’ Rifles in 1915 (before conscription), and then volunteered for service overseas with the Royal Artillery in December 1916. This decision underscores that sense of a closing door in many of his poems, but the war is by no means the only cause of impending loss. Throughout all of his poems is the sense of haste – not rush, but of a finite amount of time available to him and that which he loved. The countryside in 1914 was threatened not only by war but by the economic and demographic shifts that were emptying fields and filling the cities. Thomas’s choice of subjects in 1914 were already partly archaic – to place it into context, whilst Thomas was meeting the ancient genius loci in Wiltshire (‘All he said was: ‘Nobody can’t stop ‘ee. It’s / A footpath, right enough.’), J. Alfred Prufrock was watching ‘the smoke that rises from the pipes / Of lonely men in shirt-sleeves, leaning out of windows’ and measuring out his life with coffee spoons.

Poetry for Thomas was a way of remembering that which he loved. But he was no sentimentalist. His poems bear the record of the limits of memory and poetry’s ability to preserve against time: ‘There are so many things I have forgot, / That once were much to me, … / But lesser things there are, remembered yet’ (‘The Word’). This might be a cry many of us recognise as we search for a name, but all we can recall is the colour of the tie he wore, or the fact that her ill-fitting shoes burst a strap on the way back from the cinema one time. Everything that lives, lives in the present only: even when we are remembering, we are stationary:

The Past is a strange land, most strange.

Wind blows not there, nor does rain fall:

If they do, they cannot hurt at all.

…Remembered joy and misery

Bring joy to the joyous equally;

Both sadden the sad.

(‘Parting’)

Thomas knows the love he feels for the countryside is one-way traffic. The pearls that he forms out of this love, his poems, survive because they are beautiful and have form – but the form that they have is their own, not the rain’s, the flowers’, or the sparrows’. The poems are objects that contain something of the past which he loves; but like clumsy symbols, they are as much about themselves as they are about their subjects

Let us return to why this matters:

But memory is part of our faith. For Catholics, tradition is very important, and we cannot have tradition without memory. … ‘Eucharist’ means ‘thanksgiving’, which is why at the start of Mass it is important to call to mind (remember) not just our sins, but that for which we are grateful. And all of the Eucharistic prayers are peppered with ‘remember’, ‘in memory’, ‘recall’, ‘in remembrance’. ‘Anamnesis’ is the Greek word meaning ‘reminiscence’ or ‘memorial sacrifice’, and refers to both the memorial character of the Eucharist, and the Passion, Resurrection and Ascension of Christ.

(Roger Dawson, ‘Dangerous Remembrances’, http://www.thinkingfaith.org/articles/20131111_1.htm)

Sentimentality and nostalgia are not merely poor taste, they are spiritual traps. For Catholics, truthful memory connects us to the historical presence of God in the exact circumstances of our lives (and thus the confidence in His current and future presence). For Thomas, truthful memory was the only tool he had by which to preserve the objects of his love. What links his poems to the act of memory in the Eucharist, and distinguishes them both from nostalgia and sentimentality, is their call to action. Nostalgia is essentially passive: you put on your headphones or settle back in the audience and enjoy the sensations. A loving memory is tied with up questions that demand action: what was it really like? What was the true reality? These are the motivating and energising questions of many a spiritual search.[4]

So a healthy, loving act of memory takes place with energy and a desire to ‘see the thing as it is’. It is ambitious, not satisfied with the most obvious recollections, suspicious of simplicity. And ultimately it is aware of its limitations – no picture can capture the face of the beloved, and no poem can hold the world.

To return to the Suscipe:

Take Lord, and receive all my liberty, my memory, my understanding

What does it mean to give total control over one’s memory and understanding to the Lord? To paraphrase C.S. Lewis, if I had got further with this myself, I could probably tell you more about it.[5] But Thomas’s poems show us an attitude from where this might begin. Poems written during his army training to his two daughters and wife, find him searching for the gifts he can offer to them:

If I should ever by chance grow rich

I’ll buy Codham, Cockridden, and Childerditch,

Roses, Pyrgo, and Lapwater,

And let them all to my elder daughter.

The rent I shall ask of her will be only

Each year’s first violets

(‘If I should ever by chance’)

What shall I give my daughter the younger

More than will keep her from cold and hunger?

I will not give her anything. …

Her small hands I would not cumber

With so many acres and their lumber,

But leave her Steep and her own world

And her spectacled self with hair uncurled

(‘What shall I give?’)

And to his wife, Helen:

And you, Helen, what should I give you?

…If I could choose

Freely in that great treasure-house

Anything from any shelf

I would give you back yourself

(‘And you, Helen’)

In these poems, we hear the sound of Thomas ceding up control. The war was closing in on him, and the semi-jovial rhymed couplets of these poems are a gentle mockery of the part he is playing – the well-to-do benefactor bequeathing his riches to his family. Instead each of these poems finds him owning nothing – that which he loves is not his to give. It is a realisation of powerlessness akin to humility: ‘When I look back I am like the moon, sparrow and mouse / That witnessed what they could never understand’ (‘The long small room’).

This is what is so difficult about praying the Suscipe in a time of nostalgia: my memories are mine, are me, and every delicious or bittersweet daydream addicts me further to their taste. Centenaries are those daydreams on a national scale. Thomas’s love and honesty leads him close to the attitude of the Suscipe: ‘It is plain / That they will do without me as the rain / Can do without the flowers and the grass’ (‘What will they do?’). This release of ownership is the more touching that it comes at the end of such loving efforts to remember and preserve.

*

Thomas is not an advanced spiritual guide – his poems record the lack of solace he found. In this way, they are ‘dangerous remembrances’; dangerous too, as we prepare ourselves for a flurry of centenaries, because they highlight the self-confidence and desire for ownership in big acts of memory. Nostalgia and centenaries encourage us to treat memory as a product – to control and seal it, and by doing so, to render it no longer dangerous. We are told: Never Forget, and it is unlikely we ever will. But it is worth asking ourselves over the coming months what we are able to mean by this. What kind of control are we exerting over the past? How loving is our understanding of it?

The wish to understand the war and to pass judgement – to praise that which should be praised, and to condemn that which should be condemned – is natural and in many ways healthy. To not do so would be to close our eyes to an event that unleashed a century of suffering. But there are risks in doing this, a historical smugness that comes with distance – which has not only political ramifications (European countries promising each other ‘Never Again’, whilst they harden borders against those fleeing from wars fought with European weapons), but spiritual risks too. If our memories become less dangerous, less nuanced and true, we are closing our eyes to the hand of God.

The Suscipe acts as the soil in which we can plant our memories. It is not a call to passivity – we hear the opposite in it. It combines a love that seeks to see God in history and reality, with a humility that realises it does not own or fully comprehend that which it seeks to understand.

Edward Thomas asks the same questions in his poetry: What is the use of human memory? What is real love? These are permanent question no centenary answers.

Nathan Koblintz is a former member of the Thinking Faith Editorial Board.

[1] Particularly when faced with the trumpeting of the English Premier League regarding its creation of a “3G pitch in Ypres” – which “represents a fantastic opportunity to continue the messages of peace and understanding associated with the original Christmas Truce match of 1914.”

[2] Nostalgia was originally a medical issue for Swiss émigrés in the 17th century, curable by leeches, opium, and of course, a trip to the Swiss alps. Interestingly, in light of its shift in meaning after the first world war, Swiss soldiers were seen as being particularly prone to it: http://www.iasc-culture.org/eNews/2007_10/9.2CBoym.pdf

[3] References to poems come from The Annotated Collected Poems, (Tarset, 2008), ed. Edna Longley.

[4] And not just mental action: as Roger Dawson stresses, true memory cannot but result in ‘the radical action of Christian discipleship’.

[5] ‘I wish I had got a bit further with humility myself: if I had, I could probably tell you more about the relief, the comfort, of taking the fancy-dress off – getting rid of the false self, with all its ‘Look at me’ and ‘Aren’t I a good boy?’ and all its posing and posturing. To get even near it, even for a moment, is like a drink of cold water to a man in a desert.’ Mere Christianity (London, 1952), p.112