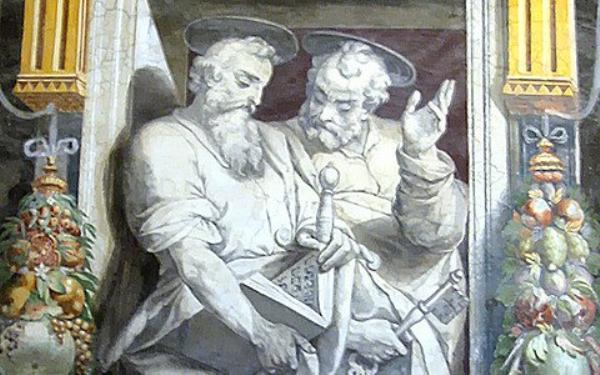

Today we celebrate the Solemnity of Saints Peter and Paul. ‘They were both apostles of Christ who sacrificed their lives to the same persecution, but their origins, personalities and achievements remind us that we live with diversity as well as uniformity in the Church of Christ.’ Peter Edmonds SJ describes how God’s grace worked differently in the lives of these two saints, neither of whom had straightforward paths to holiness.

29 June is the day set apart in the Catholic world for the celebration of the Solemnity of Saints Peter and Paul. Apart from Mary, the mother of Jesus, St Joseph and St John the Baptist, these are the only human figures commemorated in the calendar of the universal Church with a day given the rank of ‘Solemnity’. Like all saints, Peter and Paul did not come with sanctity ready-made from heaven. We respect them because in them the grace of God achieved its purpose. Such grace works in different ways. Sometimes God’s grace, like the prophet Jeremiah, has to ‘destroy and overthrow, to build and to plant’ (Jeremiah 1:10). Paul and Peter offer us instances of each of these dynamics.

In Paul’s case, God’s grace had ‘to destroy and overthrow’. Paul boasted how ‘as to the law he was a Pharisee. . . as to righteousness under the law blameless’, but, ‘ Whatever gains I had, these I have come to regard as loss because of the surpassing value of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord. For his sake I have suffered the loss of all things’ (Philippians 3:4-7). When Paul prayed to be freed from ‘the thorn in the flesh’, a messenger of Satan sent to torment him, the Lord replied, ‘My grace is sufficient for you, for power is made perfect in weakness’ (2 Corinthians 12:10). As to boasting, he wrote, ‘If I must boast, I will boast of the things that show my weakness’ (2 Corinthians 11:30). Luke in Acts gives a dramatic instance of this grace of God at work. His account of Paul’s conversion begins with Paul ‘breathing threats and murder against the disciples of the Lord’, but it concludes by describing how Paul, having met the light of Christ, had to be led by the hand and brought into Damascus. ‘For three days he was without sight, and neither ate nor drank’ (Acts 9:1-9).

As for Peter, he was a fisherman from Galilee, depicted by the Jerusalem authorities as a man uneducated and ordinary (Acts 4:13). His was a situation in which God’s grace had ‘to build up and plant’. Gospel incidents provide examples of such grace in action. When Peter sank below the waves after walking on the water, Jesus ‘immediately reached out his hand and caught him saying, “You of little faith, why did you doubt?”’ (Matthew 14:31). At the last supper the Lord said to Peter, ‘Simon, Simon, listen! Satan has demanded to sift all of you like wheat, but I have prayed for you that your faith may not fail’ (Luke 22:31-32). And when Peter had denied his Lord three times, Luke tells us how ‘The Lord turned and looked at Peter’. He then went out and wept bitterly (Luke 22:61-62).

The Story of Peter in Mark

Peter goes under at least three names in the New Testament. Sometimes he is Simon, sometimes Peter, sometimes Simon Peter and sometimes Cephas. He is referred to 181 times. His story is first given in Mark, the earliest gospel, and we can watch him as his career unfolds. He is the first of the disciples to be named. We admire him for his ready response to Jesus when he called him as he cast his net into the sea. At a word, he and his brother Andrew left their nets and followed Jesus (Mark 1:16-18). Soon we enter his house and meet his mother-in-law in Capernaum (1:29). But before the end of Mark’s first chapter, he and his companions were not following Jesus, but ‘hunting’ him. They interrupt Jesus at prayer and urge him to return to the town, but Jesus refuses. Here is a hint that Simon did not grasp what the mission of Jesus was all about (1:35-38).

But we are reassured when we find the name of Simon (now also called Peter) heading the list of the ‘Twelve whom he also called apostles’. These were called ‘to be with Jesus’, the first qualification for discipleship (3:14). He and two others were privileged to be with Jesus when he raised the daughter of Jairus from death (5:37). At the mid-point in the gospel, when Jesus asked his disciples who they thought he was, it was Peter who replied that he was the Messiah (8:27-30). We congratulate Peter because he is the first human being in this gospel to make this identification, already known to the reader from the title of the gospel (1:1).

But our congratulations turn sour when we find Jesus using a new name for Peter; no longer speaking in parables (4:33), Jesus speaks openly about the suffering ahead of him in Jerusalem. Peter in response, using the word with which Jesus addressed demons (1:25), ‘rebuked’ Jesus. So serious was this misunderstanding that Jesus addressed Peter as Satan (8:33). At the Transfiguration of Jesus, which should have brought encouragement to the disciples, they were terrified, and Peter did not know what to say (9:2-8). Peter also failed at Gethsemane when Jesus sought support from him and his companions. Jesus complained, ‘Simon, are you asleep? Could you not keep awake one hour?’ (14:32-42). Straight after this, all the disciples fled.

Jesus was taken before the high priest where all the priests, the elders and the scribes were assembled. There for the first time, he confessed his identity as Messiah and Son of the Blessed one, and spoke of himself as the Son of Man. In contrast, Peter three times denied that he ever knew Jesus, sealing this denial with an oath (15:53-72). Surely this must be the end of Peter’s discipleship. But Jesus had other plans. At the supper before Jesus’s arrest, Peter had declared with bravado, ‘Though all become deserters, I will not.’ (14:29). Although quite aware the opposite was the case, Jesus promised to meet them again in Galilee. The gospel ends with a young man telling the women at the tomb to inform Peter that Jesus was going ahead to Galilee: ‘There you will see him’ (16:7). Jesus had said to Peter, ‘the way you think is not God’s way, but man’s’ (8:34). We may well say the same about this new beginning offered to Peter.

Peter in the Other Gospels

The other evangelists record the story of Peter in a similar way to Mark. They too record his flight and apostasy during the passion of Jesus, but they make additions which serve to elevate the prestige of Peter. Luke greatly expands the story of Peter’s call and structures it according to the pattern of the call stories of great figures of Israel’s history. An experience of God is followed by an objection by the one called, then there is a reassurance and finally a mission. We find these elements in the call stories of Moses (Exodus 3:7-12), of Isaiah (Isaiah 6:1-9) and of Jeremiah (Jeremiah 1:4-7). Peter has an experience of God in the great catch of fish; he objects, for he is a sinful man; but then the Lord reassures him and promises him that he will be a ‘fisher of people’. This prediction is fulfilled at Pentecost time when 3000 are converted on the same day after Peter’s speech (Acts 2:41). The plea of Peter, ‘Depart from me, because I am a sinful man’ suggests that the original context of this scene was after the Resurrection when Peter would have been so bruised by the sin of his denials (Luke 5:1-11).

In Matthew, Peter makes an even more impressive confession than in Mark. Jesus is ‘the Christ, the Son of the living God’. At once Jesus praises Peter, and tells him that he is blessed. ‘Flesh and blood have not revealed this to you but my Father in heaven’. Peter is then given a promise and a commission. ’On this rock I will build my church and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven.’ (Matthew 16:16-19). Many experts on this gospel believe that this scene, too, took place after the Resurrection as one of the several ‘church-founding’ appearances.

In John, the most significant addition to traditions about Peter is explicitly included as a post-Resurrection story. As in Luke, the disciples have been fishing and have made an enormous catch. But this time the dialogue with Peter takes place after the fish have been landed. Three times Peter is asked whether he loved Jesus, as if in compensation for his three denials. Three times Peter affirms his love. This is how he qualifies for his appointment as a shepherd of the lambs and sheep that belong to Jesus (John 21:15-19; 1 Peter 5:1-2). Jesus’s description of himself as a good shepherd earlier in this gospel clarifies what this task involves (John 10:11-18).

The Story of Paul

In contrast to Peter, Paul never knew the earthly Jesus (2 Corinthians 5:16). He was born far away, in Tarsus in Cilicia. He was proud of his strict Jewish upbringing. His Galatian readers are presumed to know of his earlier life in Judaism (Galatians 1:13). He was a ‘Hebrew born of Hebrews’ and ‘a Pharisee’ (Philippians 3:5). According to Acts, he was brought up in Jerusalem ‘at the feet of Gamaliel, educated strictly according to our ancestral law’ (Acts 22:3). But, like Peter, he had sinned; he had persecuted the Church of God (Galatians 1:13; Philippians 3:6). ‘For this reason’, he wrote, ‘I am unfit to be called an apostle’ (1 Corinthians 15:9).In Acts, his attempts to destroy the Church are described in ever more dramatic terms (Acts 9:1-2; 22:4-5; 26:10-11). The accounts of his conversion in Acts are echoed in more sombre ways in his letters. He claimed to have received the gospel ‘through a revelation of Jesus Christ’ (Galatians 1:12), to have ‘seen Jesus our Lord’ (1 Corinthians 9:1), that the risen Jesus ‘last of all, as to one untimely born, appeared to me’ (1 Corinthians 15:8). Paul’s own writings cultivate a much plainer style than Luke in Acts.

The second half of Acts details the missionary journeys of Paul, his arrest and trials, and his journey to Rome. Paul speaks to Jewish and Gentile audiences (13:16-41; 17:22-31 etc). He defends himself before Roman governor and Jewish king (26:1-29). He performs miracles (14:8-10), he endures the hardships of prison (16:19-24) and survives shipwreck (27:1-44). Paul is often said to be the hero of the Acts of the Apostles. Paul gives his own version of his missionary and pastoral life in what he terms his ‘fool’s speech’ in 2 Corinthians (11:1-12:13). Elsewhere, his letters may give a less picturesque account of his activities, but they prove his reputation as the greatest of early Christian missionaries in his responses to the problems and dilemmas of people new to the Christian gospel.

Paul was no academic theologian, but he was a theologian in the sense that he always approached pastoral problems through theology. Any study of the nature of the person of Jesus, the character of the Church, the status of humanity before God has to begin with a study of the thought of Paul. In Philippians we find the great hymn celebrating the emptying of Christ (Philippians 2:6-11); in 1 Corinthians the church envisaged as the body of Christ (1 Corinthians 12:12-31); in Romans the need for Christ to release humanity from the tyranny of sin (Romans 5:1-21). And we can prolong the list: the hymn to love in 1 Corinthians belongs to the literature of the world (1 Corinthians 13:1-14) and his verses on the Eucharist and his summary of the gospel message about the death and resurrection of Christ give us information about Jesus dating long before the gospel accounts (1 Corinthians 11:23-34; 15:1-11).

Paul might also be described as the first Christian mystic. He could write that, ‘It is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me’ (Galatians 2:20). For him, he told the Philippians, ‘Living is Christ and dying is gain’ (Philippians 1:21). He wrote to the Galatians that he was again ‘in the pain of childbirth until Christ is formed in you’ (Galatians 4:19). And it was surely about himself that he was writing when he speaks of a ‘person in Christ who was caught up into the third heaven. . . was caught up into Paradise and heard things that are not to be told, that no mortal is permitted to repeat’ (2 Corinthians 12:2-4).

Peter and Paul

We know that Paul and Peter suffered together in the time of the emperor Nero some thirty years after the death of Jesus. The basilica of St Peter is built over his tomb. Paul, too, has a basilica in his honour, not far from the Tre Fontane, the traditional site of his beheading. They lie near each other in Rome. Did they meet in their lifetimes? In the Acts, their stories are given separately: Peter is prominent in the first half of the book and Paul in the second. They meet but once, at the so-called Jerusalem council in Acts 15. Peter speaks and Paul speaks; James adds his opinion and the meeting comes to a harmonious conclusion.

But in Paul’s letter to the Galatians, the picture is more complicated. Three meetings are recorded. First Paul visits Peter in Jerusalem, where they spend two weeks together. This took place three years after Paul’s conversion experience. We are not told what they discussed (Galatians 1:18). After fourteen years, they meet again in Jerusalem. Here Barnabas and Paul share the ‘the right hand of fellowship’ with Peter, James and John. They agree that Peter is to preach to the circumcised (the Jews) and Paul to the uncircumcised (the Gentiles). Paul is to remember the poor (Galatians 2:9-10).

Paul mentions a third meeting with Peter in Antioch, where there is a sharp exchange of views. Peter has given up his practice of eating at the same table as Gentile converts. This led Paul to disagree in public with Peter because he ‘was not acting consistently with the truth of the gospel’ (Galatians 2:13). Peter no doubt thought that he was serving the interests of Jewish Christians in their tensions with Jews who were not Christians, but Paul, because of his theological vision of what God had done in Christ, saw such divisions as a betrayal of the gospel. Ultimately Paul’s view won; for Christians, Christ is the end of the law and we have been set free (Galatians 5:1). By the time that Acts was written, this tension belonged to the past, even though in 2 Peter, the book commonly regarded as the last to be written in the New Testament, there is a warning about ‘our beloved brother Paul. . . In his letters, there are some things in them difficult to understand which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction’ (2 Peter 3:15-16).

Peter and Paul have much in common in that they were both apostles of Christ who sacrificed their lives to the same persecution, but their origins, personalities and achievements remind us that we live with diversity as well as uniformity in the Church of Christ. Paul complained to his Corinthian converts that some were saying, ‘I belong to Paul’ and others ‘I belong to Cephas [Peter]’ (1 Corinthians 1:12). His appeal that we all be united in the same mind and in the same purpose (1 Corinthians 1:10) is surely the appeal that we are to heed on this Solemnity of Peter and Paul.

Peter Edmonds SJ is a tutor in biblical studies at Campion Hall, University of Oxford.