Our individual journeys through Advent will bring us together at the crib in a few days, where we will join all those whose ‘joyful hope’ is founded in the coming of Christ. Jack Mahoney suggests that our prayer over the coming days could be inspired by some familiar yet mysterious characters, who were full of hope even though their own journey to the crib was long and uncertain.

As Christians celebrate the season of Advent, they are often invited to think of three different comings of Jesus: first his coming in history in his birth at Bethlehem; secondly his coming in the present, in the Christian assembly and especially in the Eucharist; and thirdly his coming back at the end of history, at what early Christians called the Parousia, or Return. We also see Advent as the beginning of the liturgical year, as we prepare for and celebrate the birth of Jesus, and follow his ministry through to his passion and death, then his resurrection and ascension, followed by his sending his Spirit upon the Church at Pentecost.

A German liturgical scholar I once read suggested that it would be better if the liturgical year actually ended with Christmas instead of beginning with it. The annual cycle could start with the Annunciation in March and Lent, and proceed through the life of Christ to Holy Week, the Resurrection and Pentecost, to culminate at Christmas in celebrating the Parousia, the definitive return of Christ in glory. Then Christmas would become less backward-looking, centred on Bethlehem, with all the trappings of the crib and carols, and it would have deeper theological significance as representing the climax of the Christian liturgical year. That rearrangement of the course of the liturgical year makes a lot of sense, but I am not advocating that the Church adopt it. I only mention it in order to concentrate attention on the future-orientated aspect of Christmasas we near the end of the preparatory period of Advent and begin to think of the return of Christ at the end of history.

We Christians are supposed to be longing for that. As the priest used to say at Mass after the Our Father, ‘as we wait in joyful hope for the coming of our Saviour Jesus Christ;’ and now says, ‘as we await the blessed hope and the coming of our Saviour Jesus Christ’. Joyful hope? Blessed hope? Do we really? St Peter’s second letter (3:12) mentions ‘the day of the Lord’ and urges his readers to ‘do your best to make it come soon.’ Are we actually looking forward to the return of Christ as we joyfully sing, ‘O come quickly, O come quickly’ in the advent hymn, ‘Lo, He comes,’ of Charles Wesley? There is a delightful story told of how during the reign of Pope John XXIII the Lord returned, and a young Monsignore rushed into the Pope’s office to tell him and asked desperately what they should do. ‘Look busy’, was the Pope’s reply. I sometimes think we might do well to call our own bluff and ask how keen we are that the Lord will return soon in glory and bring an end to this life.

Yet for believers this should be a time for ‘joyful hope’, especially given all the economic, political and social difficulties and problems which are besetting so many countries and individuals. Not that it should necessarily be a time for optimism, for that is quite different from hope. Optimism is a secular attitude, a feeling or conviction that things will succeed or will improve. (An amusing contrast has the pessimist saying that things cannot get any worse, whereas the optimist says, ‘Oh yes they can!’) Optimism is not the same as religious hope, which is much more trusting in God’s providence and holds a conviction that he is ultimately in charge of events.

Think of the magi, for they offer, I suggest, a wonderful symbol of religious hope. As the Church is moving through Advent to celebrate the birth of Jesus, we can think of the magi as having already been on the road for some time. They are on the way, are over the horizon, and will eventually join us at Bethlehem. They are travelling in hope. Their journey did not have to be as grim as the depressed T. S. Elliot described it in his poem, The Journey of the Magi, when he wrote of the ‘cold coming we had of it.’ They were certainly not sure of where they were going, or of what they would find when they got there. They were not optimistic; but they were hopeful. I remember a Jesuit brother who worked in the Spirituality Centre at Craighead near Glasgow years ago, who was a keen supporter of Celtic Football Club. Whenever they played a home match he would aim to get to it, but, not having much money, on Saturday morning he would go down to the main road to Glasgow and thumb a lift from a passing car. As he told me, he always set out in hope and said a prayer to the three wise men to get him a lift, and apparently they never let him down!

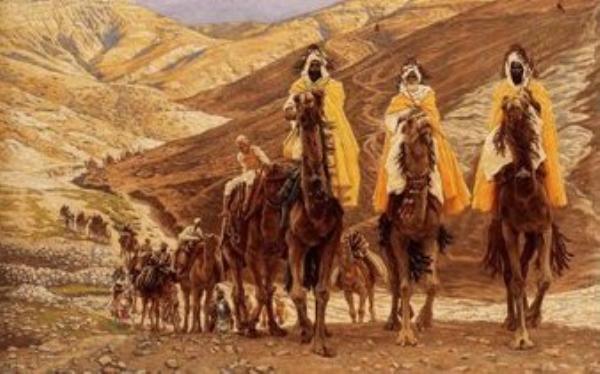

But who said they were three wise men? All that Matthew’s Gospel tells us – and his is the only gospel to include the story – is that when Jesus was born in Bethlehem, ‘wise men from the east came to Jerusalem’, asking where was this king of the Jews who had been born, since they had seen his star in the East and had come to honour him (Mt 2:1-2). That is all we were told about them originally, but then legend began to enter in, as often happened to fill in gaps in the gospel, as I wrote in Thinking Faith some time ago. If there were three gifts, gold, incense and myrrh, to be given (Mt 2:11), then presumably there were three magi, and if so they would conveniently come to represent the three continents which were then known to exist: Europe, Asia and Africa. Eventually one of them became black-skinned to show this, and they were given the names of Melchior, Caspar and Balthasar. They had ‘observed his star from its rising’, Matthew writes, and so the origin of their journey became Babylon, the centre of contemporary astrology, and they were evidently Babylonian scholars and scientists. Someone also had the bright idea that they were kings, since they seemed to fulfil the prophecy of Psalm 72:10: ‘May the kings of Tarshish and of the isles render him tribute, may the kings of Sheba and Seba bring gifts.’ So they were pictured as travelling with quite a royal retinue of servants and baggage, as artists like Tissot (above) were not slow to depict. No wonder Herod was alarmed!

The magi on the road well illustrate the new theology of hope which has developed in Christian thought since the Second Vatican Council. Influenced by Jürgen Moltmann’s Theology of Hope (SCM Press, 1967), and inspiring various theologies of liberation, the idea of hope has moved from an older attitude of sitting patiently waiting for God to improve things or remedy some situation for us. Now God is viewed as not sorting things out for us, but as doing so through us. Hope has become an active, transformative driving force which encourages believers to cooperate, or ‘work with’, God in achieving an improvement in a difficult situation.

At the Epiphany, I have always liked to think of the magi adoring the infant Jesus at the crib in Bethlehem (Mt 2:11) as representing the best of human wisdom worshipping at the feet of God and being recognised by God. Now, before that, I think that the magi travelling forward in uncertainty make wonderful patron saints of Christian hope for us in Advent, as we look forward to and work for the growth of God’s presence in our world. So, in continuing to reflect and pray about Advent in the days still to come before Christmas, we can ask for a great increase in ‘joyful hope’, stimulating us to work for the definitive coming of our Saviour Jesus Christ into our lives, our activities and our world.

Jack Mahoney SJ is Emeritus Professor of Moral and Social Theology in the University of London and a former Principal of Heythrop College. His latest book, Christianity in Evolution: An Exploration, is published by Georgetown University Press, Washington, D.C.