The new translation of the Roman Missal is now being introduced at Masses in the English-speaking world, after much discussion in recent months about the thinking behind the translation and its finer details. Musician and liturgist, Frances Novillo takes an extended look at the new translation, placing it in its historical context, explaining the principles that informed the translators and reviewing the changes that have been made to the text.

PART ONE: WORDS IN ESSENCE

Indeed, the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword... it is able to judge the thoughts and intentions of the heart. (Hebrews 4:12)

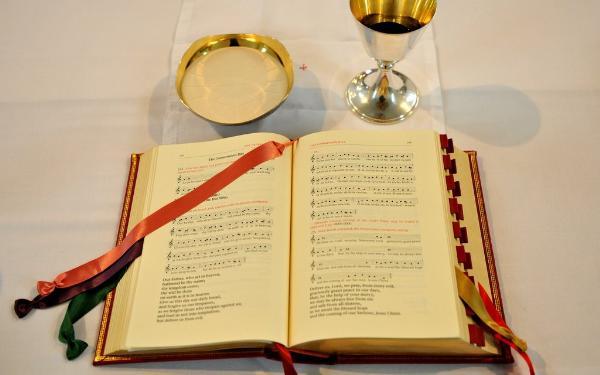

In liturgy, words are proclaimed, prayed, heard, read, written, painted, woven, beautified. They provide a source of reflection and meditation, whispered, spoken and sung. They build a doorway to God, describing and responding to him. And now the words of the Mass have changed. By the end of this year English-speaking Catholics around the world will be praying the new translation of the Roman Missal.

It is no wonder that the changes to the words of the liturgy have generated strong reactions. The concerns raised demonstrate a commendable interest in the text. If these changes were received without comment, it would signify that what is said and heard at Mass is of no importance and that would be regrettable. Even the most vehement opponent of the new translation is witnessing powerfully to the importance of the Mass. However, is a particular word or phrase lost or found really the pearl of great price?

In essence, structure and fundamentals, the Mass remains the same. During his visit to Britain last year, Pope Benedict XVI emphasised that this is a unique opportunity to catechise on the Mass as a whole. The official document governing the translation, Liturgiam Authenticam, recommends that ‘a suitable period of catechesis should accompany the publication of the new text’ (§74)2. Such catechesis was lacking in the introduction of the first English translation. In 1993, the International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) observed:

That Missal (1974) has stood the test of time but it is not perfect. The translation, though done with care, was carried out with some urgency in order to have the English texts available as soon as possible. There are some inaccuracies and other occasions where the translation lacks felicity of expression.[1]

The new translation, by way of contrast, has undergone considerable revision and debate, through official channels and among people reading study texts and leaked previews. The text was finalised in 2010 and throughout this year, training and formation has been offered to encourage parishes to introduce the text gradually in song from Easter 2011, in the Order of Mass from September and the complete Missal translation from the 1st Sunday of Advent.

Comme le Prévoit

The translators, responsible for a language of prayer used by millions, took on an enormous task, shared among several countries. Smaller linguistic groups will use the English translation to inform their own, so the pressure to achieve accuracy is increased. The 1969 document, Comme le Prévoit, which informed the 1974 English translation, explains:

The formula translated must become the genuine prayer of the congregation and in it each of its members should be able to find and express himself or herself. (§20c)

The greatest care must be taken that all translations are not only beautiful and suited to the contemporary mind, but express true doctrine and authentic Christian spirituality. (§24c)

Comme le Prévoit recognises the necessary task of future translators, saying: ‘Above all, after sufficient experiment and passage of time, all translations will need review.’ (§1)

The 1974 Missal, like some churches of its time, was not built to last! However, Comme le Prévoit has an enduring legacy in the form of ICEL. Comme le Prévoit states:

Those countries which have a common language should employ a ‘mixed commission’ to prepare a single text. There are many advantages to such a procedure: in the preparation of a text the most competent experts are able to co-operate; a unique possibility for communication is created among these people; participation of the people is made easier. (§41)

International co-operation on this scale necessitated the use of a form of English comprehensible around the world. Translators working in 1970 could not have imagined the expansion of global travel, migration and communication, nor the scale of international relationships, friendships and business partnerships which exist today, so they couldn’t have been expected to respond to this liturgically, but it is an acknowledged feature of English-speaking life in 2011.

A translation for our time

Each Missal translation is of its time. Liturgiam Authenticam admits that it is, ‘taking into account a number of questions and circumstances that have arisen in our own day.’(§7)

Catholics worshipping in their own languages for the first time, after the change to the vernacular, required a text which was accessible immediately, but there was a sacrifice inherent in this approach:

there is a general awareness that the translation, especially of the three ‘presidential prayers’ of each Mass (collect i.e. opening prayer, prayer over the offerings, prayer after communion) in many cases is too free and near paraphrase, as well as omitting some words and phrases in the Latin original.[2]

Comme le Prévoit (§34) permitted explicitly paraphrasing for the purpose of clarity and simplicity, but it is now understood as an inadequacy. By contrast, some of the newly-translated texts seem to be following the tradition for all God’s children, young and old, to put on:

…spiritual garments a little too large for them to grow into, as they will in time. And who knows what vivid image or hint of the beauty of God will remain in their mind and memory?[3]

In 1974, congregants unfamiliar with the Bible would have been oblivious to Scriptural allusions in the ritual texts. However, after 40 years of hearing Lectionary readings in the vernacular, the ground has been prepared to sow the seeds of Scripture throughout the Mass. So Liturgiam Authenticam directed the new team of translators to return to the original Latin, restoring Scriptural allusions which may now be recognised.

While it is permissible to arrange the wording, the syntax and the style in such a way as to prepare a flowing vernacular text suitable to the rhythm of popular prayer, the original text, insofar as possible, must be translated integrally and in the most exact manner, without omissions or additions in terms of their content, and without paraphrases or glosses. (§20)

Vatican II relinquished the uniformity of the Latin rite into various vernacular translations, acknowledging the effect of different cultural contexts on the practice of religion. The Directory on Popular Piety later endorsed expressions of devotion from across the world. The ritual expression of Roman-rite Catholicism was permitted to diversify and its best practice was subsequently drawn together in the Directory to inspire the whole Church. As the liturgy diversifies among many different cultures, countries and languages, the innumerable assorted elements become increasingly separated. Remaining in an ever-diversifying stage of the process could threaten, at least liturgically, the continuity and unity essential (necessary and of essence) to Catholicism. However, Liturgiam Authenticam doesn’t discredit this developmental stage, but rather promotes a rite which stands in continuity with the Second Vatican Council’s philosophy of diversification by encompassing all its richness.

This Instruction envisions and seeks to prepare for a new era of liturgical renewal, which is consonant with the qualities and the traditions of the particular Churches, but which safeguards also the faith and unity of the whole Church of God. (§7)

A time for gathering

ICEL is the alchemical vessel in which all the separated elements from assorted cultural contexts are recombined in order to create something greater than the sum of its parts. There is a time for scattering and a time for gathering (Ecclesiastes 3), and this internationally common text shared by all English-speaking Catholics symbolises that this is a time for gathering. At first glance, this new stage may appear restrictive but it is a distillation of the best of what has gone before, in the interests of balance and the quest for noble simplicity, and part of an ongoing process which will eventually lead on to another translation, for another time.

Within this broad historical and sociological context, merely changing the words is insufficient to implement the new translation. Reviewing liturgical practice as a whole and allowing the linguistic shift to draw more meaning out of the Mass on many levels honours the context from which the text has come and into which it will be received. Each person’s individual context is informed by previous experience of the Mass and changes to the liturgy. Older worshippers may claim it is easier for young people to accommodate the changes, but under-40s don’t know anything except the 1970s text. At least the over-40s have been through it before and know they can survive – as can the Church! Very young children value routine and may have only just memorised the words of prayers which are now changing.

Everyone has different hopes and expectations of the text. The deaf community seeks a text which can be communicated easily in sign language. Some wish for more gender-inclusive language, while others prefer an idiom full of poetry and mystery. There is also space for objection. Voices of dissent are just as valuable in the process as those which conform. Jesus did not choose apostles who all agreed with him or with each other and that is the model for the Church. Universality and catholicity in practice means that the Church accommodates varying personalities and backgrounds which will lead to diverse opinions, contained within the one Church.

PART TWO: REVIEWING THE TEXTUAL CHANGES

As the new Missal translation comes into use in parishes, the natural cadences and rhythms of the new phrases will emerge. There have been plenty of opportunities to preview the texts: in training groups, as well as in press leaks and online. However, liturgical texts are intended to be sounded out loud by groups in praise and prayer, and while there is value in pondering them privately, their true worth can only be assessed in public communal worship.

The changes

In the Greeting, ‘communion’ is a translation of the New Testament term koinonia, voicing the distinctive relationship between Christians, with Christ in the Spirit. It is an illustration of the nature of the Church, found in 2 Corinthians 13:13. The new translation represents a divergence from standard ecumenical formats, which usually retain the word ‘fellowship’ to the consternation of anyone with a concern for inclusive language. Liturgiam Authenticam regulated the new translation, emphasising a distinctive sound to Roman Catholic worship which has made it impossible for ICEL to prolong its membership of the ecumenical organisation, ICET (International Consultation on English Texts) and its successor, ELLC (English Language Liturgical Consultation). The official ecumenical link has been lost, but the newly-translated Mass will not prevent Catholics from praying alongside other Christians. Different denominations already vary the words of the Our Father and the new translations may offer a fresh perspective on familiar prayers, to further elucidate their meaning.

The 2010 English translation retains various versions of the Penitential Act, including ‘Lord, have mercy’. Mercy is a liturgical term which does not occupy a place in everyday vocabulary. In primary schools and catechesis, ‘Lord, have mercy’ is described as our way of saying ‘sorry’ to God, although the word ‘sorry’ isn’t actually used at Mass. It’s an example of liturgical language being counter-cultural – and perhaps that’s a good thing in a society which uses OMG and OMfG as common parlance! Comme le Prévoit emphasised linguistic accessibility, but pointed out that

the correct Biblical or Christian meaning of certain words and ideas will always need explanation and instruction. (§15a)

The phrase, ‘And with your spirit’ occurs five times during the newly-translated Mass. It honours the moment of ordination when the priest or deacon received a new spirit. Much of the liturgy is physical; worship engages the senses, and communicants are invited to taste and see that the Lord is good (Psalm 34:8). God chose an embodied human life in Jesus, yet believers are called to worship in spirit and in truth God who is spirit (John 4:24). Thus the phrase, ‘And with your spirit’ accentuates the spiritual nature of the Mass. The wording is closer to translations currently used in Spanish, French, German, Polish and Italian, and the original Latin.

Certain expressions that belong to the heritage of the whole or of a great part of the ancient Church, as well as others that have become part of the general human patrimony, are to be respected by a translation that is as literal as possible, as for example the words of the people’s response Et cum spiritu tuo, or the expression mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa in the Act of Penance. (Liturgiam Authenticam, §56)

The latter is therefore rendered now as ‘through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault’.

The new Gloria is similar to the text that was recited immediately after the change to the vernacular until 1974. Introducing the revised translation of this prayer highlights where unauthorised texts have crept in, including versified paraphrases, which may have entered common use via children’s groups or schools who were permitted to use such texts by the Directory on Masses with Children although this does not apply to regular Sunday parish Masses. Certain paraphrased settings are fun to sing, but Liturgiam Authenticam states unequivocally that ‘paraphrases are not to be substituted’ (§60, referring to the General Instruction of the Roman Missal).

The conclusion of each reading has been shortened to, ‘The Word of the Lord’, paralleling equally short phrases, ‘The mystery of faith’ and ‘The Body of Christ’ heard later in the Mass. Custom has until now varied across the English-speaking world – the USA has used ‘The Word of the Lord’ for some years now. Arguably, ‘This is’ limits the understanding of the Word to the reading only – or even to the book itself - when in fact the Word permeates the entire Rite and its participants.

The Creed is to be translated according to the precise wording that the tradition of the Latin Church has bestowed upon it, including the use of the first person singular (Liturgiam Authenticam §65).

The newly-translated Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed is thus analogous to the Baptismal Promises where respondents avow ‘I do’, not ‘We do’, even when a group say it on behalf of one infant, or a congregation reaffirms baptismal promises together. Also within the Creed, the unique word ‘consubstantial’ describes the matchless relationship between God the Father and God the Son.

Fidelity and exactness with respect to the original texts may themselves sometimes require that words already in current usage be employed in new ways, that new words or expressions be coined, that terms in the original text be transliterated or adapted to the pronunciation of the vernacular language (Liturgiam Authenticam, §21)

In the new translation of the Sanctus, the ‘Lord God of hosts’ is acclaimed. This name for God is heard commonly at funerals in the reading from Isaiah 25:6, familiarising a broad congregation with this imagery. The Lord God of hosts prepares the heavenly banquet, so this title is used appropriately at the beginning of the Eucharistic Prayer leading towards Communion. Three new translations of the Memorial Acclamations are addressed to Christ, who is made present in a very special way at this moment in the Mass. It is a communal response to the preceding words of the priest in dialogical form.

Scripture resonates clearly in the words used before the distribution of Communion. ‘Behold the Lamb of God’ echoes John the Baptist’s recognition of Christ in John 1:29. Some parishioners are unable to receive Communion, but join with John the Baptist acknowledging Christ at a distance. The priest issues the invitation from Revelation 19:9: ‘Blessed are those who are called to the supper of the Lamb’, but they are not the only blessed ones, for John the Baptist was dearly loved by Christ although he did not witness the fullness of Jesus’s mission on earth. The combination of the two texts recognises the different levels of participation in the Eucharist by people worshipping together. The assembly’s collective response adopts words from an unexpected source – a powerful but not particularly spiritual centurion who recognised his unworthiness before Jesus when he requested healing for his servant (Matthew 8:8, Luke 7:6-7). His belief was that God can work marvels within each person regardless of circumstances, extent of need and measure of faith. The new texts acknowledge that the healing transformation occurs at the profound level of the soul.

Bishops at the Synod on the Eucharist in 2005 requested a stronger sense of mission in the words which conclude the Mass. This Synod yielded the Papal document, Sacramentum Caritatis and eventually provided additions to the Missal in 2008 which now appear in the 2010 English translation.

Priests have a big task to change the words they’ve memorised, co-ordinate familiar gestures with new texts and guide the assembly through the process. Intelligibility and clear delivery was advised by Comme le Prèvoit in 1969 and is equally important today. Some of the sentences in the new presidential prayers are as long and complicated as those found in St Paul’s epistles, yet readers regularly prove these can be negotiated successfully. Scripture infuses the texts. In Eucharistic Prayer II, there is a beautiful image of ‘sending down your Spirit upon them like the dewfall’, reminiscent of the provision of manna with the morning dew. It is an allusion to holy water and Baptism, and when the text is used in Advent there will be additional resonances with the seasonal plainchant, Rorate Caeli: ‘Come, Saviour, come like dew on the grass, break through the clouds like gentle rain.’

Restored to Eucharistic Prayer I is the phrase: ‘he took this precious chalice in his holy and venerable hands’. In 1969, Comme le Prévoit decided that the English would misinterpret the word ‘venerable’ to mean elderly (§18.2), so the 1974 translation yielded merely, ‘he took the cup’. The new approach is faithful to the Latin, and opens up additional linguistic and spiritual treasures. For example, it is suggestive of the hands of the Father in Rembrandt’s Prodigal Son and the ‘hands that flung stars into space to cruel nails surrendered’ in Graham Kendrick’s, ‘Servant King’ song. ‘From the rising of the sun to its setting’ replaces, ‘from east to west’ in a more accurate translation of Psalm 113:3 and Malachi 1:11, quoted in Eucharistic Prayer III. Similar imagery is well-known from the hymn, ‘The day thou gavest, Lord, is ended’, with its illustration of continuous praise.

Time will tell

It takes time to accept and implement change. This is no bad thing, apart from for those people who would like to ‘get Mass over with’ in 20 minutes! Those who prepared the text took their time, going slowly, exploring cautiously the possibilities and the end result includes increased references to pauses and silences during the Mass. Time is necessary to assimilate the novel phrases, to read, absorb, remember and not stumble over them. Time is valuable to appreciate the imagery of the words and ‘the finer shades of meaning or emotion evoked by them’ (Liturgiam Authenticam §52).

Comme le Prévoit outlined the purpose of the words of liturgy in this order: communicating between people; Christ communicating to his people; and the people communicating with God (§5). Perhaps this hierarchy was not intentional, but after Vatican II comprehension by the people had to be a priority for liturgy in the 1970s. In 2011, in a society which confesses all to therapists, support groups, social networking followers and the national media, liturgical language which turns attention back to God may be a refreshing and necessary change. Liturgiam Authenticam (§19) seems to re-arrange the priorities, stating that the words of liturgy are the means by which God communicates with the Church and by which the faithful respond.

After the Philosopher ponders the time for every activity under heaven, he muses:

I know that whatever God does endures forever; nothing can be added to it nor anything taken from it; God has done this so that all may stand in awe before him. That which is, already has been; that which is to be, already is; and God seeks out what has gone by. (Ecclesiastes 3:14-15)

In searching for God in the new translation, blessings may be discovered. Something which was lost may be restored. More of God's enduring, awesome nature may be discovered. The richness of these texts can be revealed by careful elucidation, clear leadership and due time to savour them; or it may be obscured by anxiety, poor preparation, and haste. The changes can be implemented in a way which delves deeper into the mystery which is celebrated, or startles worshippers away from what is most precious about the sacrament. Time will tell how the words which have been wrangled over, debated and discussed, settle into use in prayer, praise and petition, shaping the future of the Church and the public expression of Catholic faith.

Frances Novillo is a musician and liturgist based in the parish of Mary Immaculate and St Gregory the Great, High Barnet. She is a Regional Music Adviser for the Royal School of Church Music.

[1] ICEL report to the United States Bishops’ Conference, 17 June 1993, p.3. Quoted in Maurice Taylor, It’s the Eucharist, Thank God, (Decani Books, 2009) pp.41-42.

[2] Taylor, It’s the Eucharist, Thank God, pp.41-42.

[3] Dorothy Coddington, writing in 1923, quoted by Julie McCann in Spiritual Garments: A handbook for preparing liturgical assemblies in schools (Decani Books, 2006)

More articles on the new translation of the Missal on Thinking Faith:

![]() ‘Domine, non sum dignus’ by Andrew Cameron-Mowat SJ

‘Domine, non sum dignus’ by Andrew Cameron-Mowat SJ

![]() ‘And with your Spirit?’ by Jack Mahoney SJ

‘And with your Spirit?’ by Jack Mahoney SJ