What became of all that wine at Cana? Where did the Holy Family get to in Egypt? Who was the mysterious young man who ran away from Gethsemane? Fr Jack Mahoney offers a light-hearted look at attempts to increase our knowledge of Jesus and the Gospel.

Fr Paul Edwards, an English Jesuit who headed the St Beuno’s Spirituality Centre in Wales, once wrote a delightful series of essays on characters in the Bible for the inside front cover of The Month which he later published as People of the Book (Templegate, 1987). In this he filled out imaginatively and reflectively the often meagre details which the Bible had provided about these individuals and, in so doing, he was satisfying what seems to be a feature of devotion which it shares with nature, that it cannot abide a vacuum. In aiming to fill out the contents of the Bible, he was following a tendency to be found in the Church since its earliest years, that of what I call filling gaps in the Gospel.

Apocryphal fillings

There is a body of early Christian literature that we today term the ‘apocryphal’ books; that is, literally, books which are unlikely to be true (the best account is The Apocryphal New Testament, ed. J. K. Elliott, Oxford: 1993). Of course, at the time when they first appeared, these books were not yet identified as ‘apocryphal’; rather, until they were judged unacceptable they jostled for recognition alongside the works that were in time recognised by the Church as a whole as the authoritative ‘canon’ of the Bible.

Much of the content of the apocryphal gospels was aimed at promoting the theological movement known as Gnosticism, which was condemned as heretical in the second century. It held that secret knowledge (gnosis) about God was available to an elite and ascetical group of believers, who could have direct mystical access to the deity. For example, the rediscovery in the 1970s and the publication in 2006 of the apocryphal Gospel of Judas, which we know to have been attacked in its day by orthodox theologians, excited a number of people into reassessing orthodox Christianity, and envisaging Judas’s role as that of betraying Jesus with the latter’s secret agreement, contrary to the awareness of the other apostles. Again, the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas is best known as purporting to provide a collection of ‘secret words’ of Jesus addressed to the apostle Thomas, which do not occur in the four canonical gospels, though there are many similarities and echoes. Some of these sayings may possibly be authentic – after all, it is only from one verse, Acts 20:35, that we know of Jesus’s saying that ‘it is more blessed to give than to receive.’

By contrast, other apocryphal writings were more innocently concerned to provide information to feed the hunger of pious believers who were eager for details concerning the life of Jesus, especially relating to his childhood about which regrettably little information had been provided by the Gospels. There is some similarity between this approach and the method of prayer known as ‘contemplation’ taught by Ignatius of Loyola in his Spiritual Exercises, in which one puts oneself imaginatively into a Gospel scene, watching and listening to what is going on and taking a prayerful imaginative part oneself in the action. Among Jesuit retreat directors there is a story (apocryphal, I hope) about a woman once involved in this method of mental prayer who was persevering in contemplating the Last Supper but who was dreadfully distracted because she was afraid she had put Jesus in a draught! One of my distractions in prayer occurs whenever I think about the Gospel feeding of the five thousand, where we are told that once everyone’s hunger was satisfied, twelve baskets of fragments were collected (Mk 6:43). ‘Twelve’ I can understand, with the apostles all being involved in gathering up the leftovers; but where on earth did they get all those baskets?!

However, my major distraction comes from the scene in which Jesus is preaching and is informed that his mother and brothers and sisters have turned up and want to speak with him (Mk 3:32). Jesus is reported as typically turning the news into a statement that all those who obey God’s will are his mother and brothers and sisters (Mk 3:34), but that leaves unanswered my persistent question: what did his mother and brothers and sisters want with him? We are told elsewhere that on one occasion his family tried to restrain Jesus when they thought he was neglecting himself in his enthusiasm (Mk 3:21), but quite possibly they had another reason here for coming to have a word with him. So what was it? Perhaps it was to give him family news? To let him know that Joseph his father was ill, or even had died? Or did they want to ask Jesus if he was planning to attend this wedding coming up in Cana (Jn 2:2)? As for the wedding in Cana, that creates another gap: whatever became of all that excellent wine which Jesus produced towards the end of the reception (Jn 2:6-10) – six jars holding twenty or thirty gallons each?

The apocryphal writings relating to Jesus’ childhood fill in his ‘hidden life’ with various tales of his miraculous deeds. The Infancy Gospel of Thomas describes how the youngster modelled some sparrows out of clay and, when he clapped his hands, they flew away. As a three-year-old in Egypt he gave life to a dry fish. He restored children to life who were killed in accidents and perplexed his teachers with his superior (divine) intelligence. Out of one grain of corn he grew a harvest large enough to feed all the poor in the village, and he once miraculously extended a beam of wood to save Joseph the carpenter embarrassment.

The legendary Protevangelium of James concentrates by contrast in pious detail on the birth and youth of Mary who would become the virgin mother of Jesus, and on his conception and birth in Bethlehem. It informs us, as one may expect, that Mary herself was born miraculously as a result of prayer, to a childless elderly couple whose names are given as Anne and Joachim, and that she was consecrated to the Temple from an early age to be prepared for her divine motherhood. The spirit of the apocrypha was captured exquisitely by Titian in the sixteenth century, with his painting of The Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, showing the self-composed four-year-old dressed in her best blue dress entering the Temple in Jerusalem, carefully holding up the hem of her gown in one hand while confidently manoeuvring the steep flight of steps into the Temple, and extending her other hand in greeting to the High Priest. He is waiting up at the entrance with his attendants in all his elderly magnificence, prepared to receive her into his care – and possibly looking a little apprehensive as he wonders what he may have let himself in for! It was he who decided later that Mary should marry the respected widower Joseph who already had a family. This neatly answered, for those who were concerned to respect Mary’s permanent virginity, the difficulty of Jesus being reported several times in the Gospels as having brothers and sisters, Joseph’s previous family providing Jesus with step-brothers and sisters.

The Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew aimed also at promoting the veneration of Mary. It introduces the traditional ox and ass adoring the infant Jesus in the manger. Then as the Holy Family journeyed to Egypt to avoid the malevolence of Herod, wild animals adored Jesus and led the way through the desert (an echo of paradise), and as the family rested once in the shade of a high palm tree, Jesus had it lower its branches to provide dates for his mother and produce a spring of water from its roots to refresh them all. As they eventually arrived at a city in Egypt and entered its temple, all the 365 idols there prostrated themselves and shattered into pieces before the divine child.

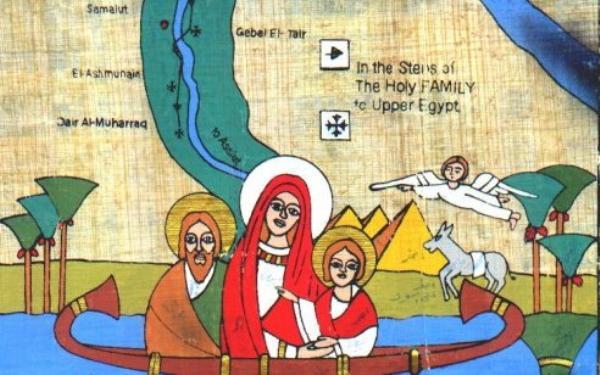

The flight of the Holy Family and its time in Egypt, totally lacking in details as they are in the canonical gospels (Mt 2:13-15), have always had a mild interest for me, and I cherished a holy picture I once had from China which showed Joseph, Mary and Jesus with oriental features and dress travelling through the rice paddies in a sampan being poled along by Joseph. In Manila, in the Family Institute there, I admired an impressive Filipino statue of all three riding through the mud, mounted somewhat precariously on the back of a large water buffalo. And somewhere in a village church in England I have come across a sculpted grouping of Joseph and Mary seated exhausted by the roadside while a young bright-eyed Jesus is looking excitedly down the road at what lay ahead. On holiday once in Alexandria I had evidence in a Coptic Church of the understandable Egyptian devotion to the Holy Family when I came across a charming wall map showing their itinerary through Egypt and marking as shrines up and down the Nile all those places where they had stayed in the course of their journey! Details of the Holy Family’s itinerary in Egypt over some four years were later revealed by Mary, in a dream naturally, to a Coptic Pope in the fifth century. I have always regretted not buying a copy of the map.

The Dormition of Mary

One especially popular apocryphal work of devotion dating from about the fourth century described the ‘dormition’, or falling asleep, of Mary, and became a medieval best-seller, doing much to popularise the belief in Mary’s assumption into heaven. (‘Falling asleep’ in the Lord was an early Christian synonym for dying, in anticipation of being awakened at the resurrection.) According to this affectionate account of Mary’s last days on earth, about which there is a complete gap in the canonical Gospels, she was informed of her impending death by an angel – none other, of course, than Gabriel – and she journeyed again to Bethlehem, summoning John and the other surviving apostles to join her there from wherever they were engaged in preaching the Gospel. They were conveyed from different lands by the Holy Spirit, including (interestingly) Peter from Rome, John from Ephesus, Paul (!) from Tiberias, Thomas from India and James from Jerusalem. Other disciples who had died were brought back to life by the Spirit, who warned them not to think the resurrection was occurring but to realise that they were being prepared to be with Mary on the day of her departure for heaven. Angels and heavenly phenomena surrounded the house, many sick people were cured in the region, and the whole of Bethlehem and its inhabitants marvelled as they had done at the birth of Jesus there. Mary and the apostles were then transported by the Spirit to Jerusalem, where she died. The apostles copied the burial of Jesus, laying her body in a new tomb in Gethsemane, where it stayed for three days before being summoned from the tomb by Jesus in glory and being transported by the angels to paradise, after which the apostles were returned by the Spirit rejoicing to their respective evangelising locations.

In some versions of the Dormition of Mary, as in a version alleged to come from Joseph of Arimathaea, a diverting episode describes how Thomas arrived too late to be present at Mary’s deathbed and was chided by Peter for being absent again, as he had been when Jesus had first appeared to the others after his resurrection. Thomas apologised and asked where her body was, but when the apostles indicated Mary’s tomb Thomas declined to believe them (again!) and indeed, when the apostles opened the tomb they found, to their confusion, that the tomb was empty and Mary’s body was not there. Then Thomas explained how he had been saying Mass in India (and was still wearing his priestly vestments) when he was transported to the Mount of Olives. While rushing over the hill heading for Jerusalem he looked up into the sky and actually witnessed Mary being assumed into to heaven, in proof of which he produced her girdle which she had thrown down to him. Game, set and match to Thomas!

The mysterious young man

Finally we can consider the gap surrounding the mysterious young man, mentioned only in St Mark’s Gospel, who fled from Gethsemane when Jesus was being arrested. Who was he? What was he doing in the garden? And why did he run away? All that we are told is that ‘A certain young man was following him, wearing nothing but a linen cloth. They caught hold of him, but he left the linen cloth and ran off naked’ (Mk 14:51-2). For lack of any other explanation, some commentators, according to a second century tradition stemming from Papias, suggest that this young man was Mark himself who, they suggest, provided here a personal reminiscence which only he would know about. However, others also could have witnessed and remembered the event, and Papias comments that Mark had never heard or followed Jesus (Migne, Patrologia Graeca 20, 300), which scarcely agrees with the proposal that he was the young man in Gethsemane. In any case, the identification with Mark explains nothing about the incident, leaving the mystery still to be solved.

I like to think that the young man who ran away naked from Gethsemane was in fact the ‘rich young man’ whom we met earlier in Mark’s Gospel, asking Jesus how he could enter into eternal life (Mk 10:17-22). Jesus had advised him disconcertingly to sell all his possessions and give the money to the poor and then to follow Jesus, but ‘when he heard this, he was shocked and went away grieving, for he had many possessions’ (10:22). I suggest that the rich young man’s desire for eternal life kept nagging at him, like many a vocation, and eventually he decided to accept Jesus’ challenging invitation to become one of his followers. He sold up everything he possessed and handed over the proceeds to the poor, leaving himself with only a rather expensive linen shift to wear; and he then set out to find Jesus, knowing that he and his disciples tended to spend the night in the garden of Gethsemane when they were in Jerusalem. However, it so happened that on that evening Jesus and his disciples were having supper in the city and were delayed, so the young man found himself alone in Gethsemane, and he fell asleep while waiting for the others to turn up. When they did arrive, Jesus went further into the garden to pray and the apostles likewise fell asleep (Mk 14:32, 37). When Jesus had finished praying Judas arrived with his cronies and they arrested Jesus (Mk 14:41-6). The young man was awakened by the tumult of the crowd, and when he saw Jesus being arrested he lost his nerve and tried to make a bolt for it. However, he was grabbed by the guards and ‘he left the linen cloth and ran off naked’ (Mk 14:51-2).

So he had not after all had the chance to follow Jesus. Was that the end of his seeking? Or did he manage later to become a disciple of the risen Lord? We do not know, of course; or perhaps, rather, we cannot know about this or other gaps in the Gospel, at least for the present. The New Testament writings which we possess and acknowledge as canonical, that is, the four gospels and a collection of occasional letters, have survived by comparison with others which may have perished, but we are in no position to know what writings may still await our discovery.

In considering the apocryphal New Testament writings which we possess we can usefully distinguish between those which were produced for apologetic and polemical purposes to promote a Gnostic version of Christianity, and the others born more to satisfy the devout curiosity of the faithful by filling in what were considered gaps in the story of Jesus’s life as told in the Gospel. In the latter case it is possible to dismiss their naiveté and credulity, of course, but one can also sense more positively almost a feeling of the faithful sharing in a sort of intimate family gossip. They are perfectly comfortable with their religion and with their belief and unguarded trust in God. I am reminded of a term used by Ignatius of Loyola, that of familiaritas with God, which does not so much mean ‘familiarity’ with God, but more having a family feeling, or feeling completely ‘at home’ with God and the things of God. It is an enviable religious sentiment, however it may find expression.

Jack Mahoney SJ is Emeritus Professor of Moral and Social Theology in the University of London and author of The Making of Moral Theology: A Study of the Roman Catholic Tradition (Oxford, 1987).