The Archbishop of Westminster has delivered a major lecture on the shape of the Catholic Church in England and Wales since the restoration of the hierarchy. In part one of the Cardinal’s lecture, he looks at how his predecessors have led the Church’s response to the questions asked of it by society, and asks how their examples can help us to face today’s challenges.

Introduction: Weathering an English Spring

In my idle moments, I often reflect on the lives and times of my nine predecessors as Archbishop of Westminster. It began in 1850 with the restoration of the hierarchy. The first Cardinal, Wiseman, wrote a pastoral letter to the people of England and Wales entitled, ‘From out the Flaminian Gate’. In it he said, “Catholic England has been restored to its orbit in the Ecclesiastical firmament from which its light had long vanished and begins anew its course of regularity, around the centre of unity.” While rallying the community with a sense of purpose, Wiseman’s words also stirred up a hornets’ nest. It prompted Queen Victoria to ask, ‘Am I the Queen of England or am I not?’ To the Prime Minister, John Russell, the act of restoration was the ‘aggression of the Pope on Protestantism’. Poor Wiseman had to dig himself out of a hole and he replied by issuing another letter entitled, ‘An appeal for fair play and reason on the part of the English people.’

This was a more humble letter and spoke of the dire circumstances of so many Catholics. Many were immigrants from Ireland and elsewhere and they lived in appalling poverty. The restoration and building up of the community – spiritually as well as materially – was not easy. But those early years after the restoration of the hierarchy were years of promise. The hopes of that period were perhaps summed up in a most wonderful sermon preached by Newman entitled, ‘A Second Spring’, which he gave to the assembled bishops and the first provincial synod held at Oscot College. The metaphor of 'spring' was an apt one, but Newman gave it a witty and profound turn. He said, “but still could we be surprised my fathers and my brothers, if the winter even now, should not yet be quite over. Have we any right to take it strange if in this English land the springtime of the Church should turn out to be an English spring - an uncertain anxious time, of hope and fear, of joy and suffering, of bright promise and budding hopes, yet withal of keen blasts and cold showers and sudden storms.”>

The vision and identity of the Catholic community in England and Wales during the 50 years following the restoration of the hierarchy could be summed up in two aims: “Keep the Faith” and “The conversion of England.” The vision of successive bishops here in Westminster and elsewhere in this country was to care for their Catholic people, to ensure that the faith which had been handed down to them by the grace of God was kept and held in an atmosphere and in a culture that was suspicious and antagonistic to the Catholic faith. Without in any way compromising the loyalty of Catholics to the country, there always lingered the hope that one day England would be restored to the ancient Catholic faith. It may have been a dream but it was always there in the prayers and aspirations of the Catholic people, especially those who held the memory of the trials and sufferings of our forebears, of the men and women who had died for their faith in penal times. Running with this was also the desire of an immigrant Catholic community to be recognised as a productive and trusted part of British society. There was, too, the concern of the indigenous recusant tradition not to lose its place in shaping the Church to which it had born heroic witness through the centuries.

These aims were the focus of the Catholic Church for two thirds of the next century. During the period of my predecessors, Cardinal Bourne who reigned from 1903 until 1936, Cardinal Hinsley, Cardinal Griffin and Cardinal Godfrey, the steady consolidation of the Catholic Church took place. It was not without its troubles and difficulties, but in these years the Catholic Church grew. Schools were built to educate the faithful not only in the faith but so that gradually they could make social and economic progress. Hospitals, nursing homes and care homes were also built. Many of them not only cared for Catholics, but for others who wanted to benefit from the ethos of these Catholic institutions. For almost 100 years the Church was marked by that rhythm of consolidation and growth. It had a strong sense of its identity and mission coherent with its own history, experience and teaching – ‘Keeping the Faith and the conversion of England.’

And then in 1962 we have Vatican II. I think it must rank as one of the most significant councils in the life of the Universal Church, and it was to radically alter the identity and vision of the Catholic Church in this country. Cardinal Heenan, a man whom I knew well and greatly admired, had the unenviable task of steering the Church in Westminster and leading the bishops in the turbulent years both during and following the Second Vatican Council.

To the Council itself, Cardinal Heenan’s attitude was rather ambiguous. One historian, Adrian Hastings, recounts that there was a story that two groups of journalists each selected a football team from among the Council Fathers: one to represent the conservatives, the other to represent the progressives. When they compared notes they found that each had selected Heenan to play centre forward!

Cardinal Heenan generally backed reform, but was often undermined by events. The defection of many priests at that time pained him greatly and the reaffirmation of the traditional teaching on contraception in the Encyclical Humanae Vitae caused him much anguish and trouble. The years of his Episcopate and, indeed, the long tenure of his successor Cardinal Basil Hume, found a Catholic Church in a very curious state. It could no longer claim in the old sense that its purpose was the conversion of England because it could not ignore the fact that we were now committed to serious ecumenical dialogue with fellow Christians and, in particular, the Church of England and the Church in Wales. The recognition of common baptism, Ecumenical sensitivity and an understanding of the fullness of unity which was still to be attained was part of the teaching of the Vatican Council and could not be ignored. Even more so the slogan, ‘Keep the Faith’, did not have quite the same ring about it.

Cardinal Hume managed in his own persona to suggest that Catholicism was part of English life. He himself became, as it were, almost a part of the Establishment. His period of office for the Catholic Church had been a high profile one in public life, much of it due to his own outstanding witness. Adrian Hastings summed him up by saying, “In retrospect, what matters most about Basil Hume, was not the correctness of every opinion or policy, but his spiritual integrity, recognition of which united Catholics of very differing theological opinions as well as the national community as a whole. He was a sound teacher but a superb witness through the gentle holiness of his behaviour and, as he said himself, “modern man listens more readily to witnesses than to teachers.” All of this leaves the Catholic Church of my time and your time still striving clearly to articulate and live out its identity, its vision, its hope.

As I look back I am struck by the continuing prescience of Newman’s homily on “the Second Spring”, preached over 150 years ago. The Catholic Church in England has lived a very ‘English Spring’, with its times of promise and growth but its moments of ‘keen blasts and cold shows and sudden storms’ as well.

The Present Time: Ad Extra

I want now to look at some aspects of that springtime landscape today, to reflect with you, first, on some of the challenges posed by our culture and, secondly, to speak about some central aspects of our life as a Church which I believe we are being called to deepen and to cherish. Let’s look at some challenges posed by our secular culture.

I have been a priest for over half a century and a bishop for more than 30 years. These have been years of considerable change in the international situation, in our society and also in the Church. Fifty years ago I think most of the values that the Church wanted to uphold were also those that society itself would have agreed with. I am in no doubt that many still recognise and admire the Church’s social and charitable work. But for others the Church and indeed Christian life seems to be out of step with ‘the spirit of the times.’ There has been a subtle but deep change in the way the Catholic Church has been perceived by contemporary culture. It is not that it meets with indifference or even hostility – although that is certainly noticeable – rather it is heard with certain incomprehension. Incomprehension not only makes it difficult for the Church, and indeed, individual Christians, to make their voice heard, it also means that there is the risk of distortion and caricature. Yet I believe the Church has a perspective and a wisdom which our society cannot afford to exclude or silence. The Church’s teaching has the whole human good in mind; that is why it is not simply one lobby group among others. Let me give two examples:

The Economy

Faced with the current global and economic crisis, it may seem that the Church’s social teaching is the last place to look for ideas. Prayers perhaps, ideas no! I think that would be a mistake. It would take another lecture, I fear, to show why but let me just point in that direction. One of my predecessors, Cardinal Manning, helped shape the beginning of the Church’s contemporary social teaching. Manning’s writing on the social and economic conditions of the poor, combined with his practical work for them and organised labour contributed to Rerum Novarum. He reminded Victorian culture that the worker was not a commodity purely subject to the economic demand or lack of it; the worker was a human being first and should be treated as such. He was clear that the economy must operate within a moral framework and exists to serve the common good, which is rooted in the good of the human person. If it forgets this, it becomes destructive of the very good it is intended to serve. In other words, money is not an end in itself. His words are very relevant in today’s economic climate. The Church does not offer a blueprint for economic policy, but it does argue that if the market is to serve the common good of all then it demands a strong ethical framework and effective regulation. One important test of this is to look at those who benefit. Here the Church is has always maintained that the common good cannot be secured if it means the poor just get poorer. The poor must always be given effective preferential consideration. No action, even in critical times, should further disadvantage them or weaken their capacity to participate in the economic system.

The Family

The economic crisis not only places great strains upon our financial institutions and the public purse, it has immediate and long lasting consequences for that most fundamental of all our human and social institutions, the family. We cannot be fulfilled persons without others – we are made for community. That means we must seek to sustain the health of those social institutions which are the foundations of a civilised and humane social sphere. The Church itself is one of these social spheres and that is why she has always recognised the importance of the family. The family is not only the domestic church; it is also the foundation of society. We can see that even in times of political and social collapse, the family has the power to survive and enable others to survive. It is from the family that society can rebuild itself. That is why I believe the Church is so right in continuing to emphasise the fundamental importance of marriage and family life. Socially, our culture has embarked upon experimentation with the meaning and structures of marriage and family. There is a danger that we come to undervalue their importance for human flourishing and for the strength of our cultural and civic life. A failure to appreciate the personal as well as social and economic importance of these two foundational institutions risks a profound cultural and human impoverishment. There is much manipulation of the concept of marriage today, but it should never blind us to the real value of marriage understood as a lifelong commitment between a man and a woman open to the transmission of life ordered to the good of spouses and their children. Its seems strange that one should have to preach this in our time, for when asked what is most important to them in survey after survey, people consistently place family at the top of the list; high above health or wealth. We need to secure these goods for the whole of our society and that they should enjoy legal and financial recognition and support.

I hope these two brief examples serve to make the point that the Church is not just another lobby group. It has both balance and insight which can get lost in a caricature or the prejudice that exiles it to a purely private realm of esoteric practice and belief. Taken together, the lack of ‘synch’, ignorance, and an aggressive secularism which tries to persuade us that every defeat of the Church and restriction of Christian work and influence is a social and personal gain, means that the relationship of the Church to culture is constantly being reshaped. We need, what some have called, a new apologetics of presence.

Towards a New Apologetics of Presence

What might this mean for us? Certainly, we know that there will always be a sense in which Christian life will always swim against the stream. Indeed it is that different way of seeing, that different way of being, that is the gift of faith to every culture. I think, though, that this difference is a genuinely creative encounter with culture; it is not an unfortunate by-product of being out of sympathy with contemporary trends. The distinctive way of being Christian is surely grounded in the way in which the Church understands the dignity and destiny of every person before God and their infinite value in His eyes. And it is this very depth of understanding – we might call it loving – that also gives an attunement to the longing and desire for what is genuinely good and life-giving that every person has, whether they share our faith or not, whether they can articulate it or not.

This is why the Church’s first word should never be “No”. It is always a “Yes” to the fundamental calling and dignity of life, through which we come to see more clearly the necessary “Nos” that must also be uttered if the truth is to be spoken. To be sure there is much that is deeply troubling about our culture and its values. And in fact it is tempting – and certainly headline-making – simply to list what is wrong. One could say, for instance, that we now live not in a liberal but a libertine society in which all moral and ethical boundaries seem to have gone out the window. But that is too quick, and it ignores the fact that there are very many people trying their best, deeply concerned about the future, and alive to the humanly destructive power of so many forces at large. The truth is that to be human is to be deeply tempted to be good. And what is needed is a renewed sensitivity to the moral and ethical dimensions of living which very many want to see more firmly embraced and spoken of, and in particular the importance of individual personal responsibility, which is also part of mature freedom. We need to encourage and affirm the good in each person, rather than simply naming the bad. It is only if the joys and hopes of humanity are shared first that true and lasting change is possible.

Two weeks ago I gave an interview to The Times. The two women journalists who interviewed me, not necessarily Christian, seemed remarkably attuned to the values that the Church speaks about. They were mothers, and deeply concerned about the values that they wanted to give their children – those simple basic lights we need to guide us through the complexities and changes of our lives. They wanted to give their children values that would last, that one could live by and build a life on. Those women were good parents and I believe they expressed a heart-felt concern which the majority of parents share about the emptiness and transience of so much that passes for standards and values in our society. They were searching and they need support to have confidence that their intuition was a good one. How interesting then in a survey reported this week on the BBC almost two-thirds of those questioned said the law "should respect and be influenced by UK religious values", and a similar proportion agreed that "religion has an important role to play in public life".

Many of the arguments of secularism seek to offer a new and liberated self-sufficient humanism. Yet, I think, they can only end in the death of the human spirit because they are fundamentally reductionist. They have an impoverished understanding of what it is to be human which means that in the end they have no satisfactory defence against the instrumentalisation of the person. Pope Benedict expresses this when he says, “People today need to be reminded of the ultimate purpose of their lives. They need to recognise that implanted within them is a deep thirst for God. They need to be given opportunity to drink from the wells of his infinite love. It is easy to be entranced by the almost unlimited possibilities that science and technology place before us; it is easy to make the mistake of thinking that we can obtain by our own efforts fulfilment of our deepest needs. This is an illusion. Without God who alone bestows upon us what we by ourselves cannot attain, our lives are ultimately empty.”

What marks the Church of Wiseman, Manning, Hinsley, Heenan and Hume is its response to the challenges that faced it. In many ways it was a poor and under-resourced Church, but what it may have lacked in material things it made up for in energy and confidence. This does not come from any recognition of the Church as an institution. One day the Church may be in favour with the secular powers, another it may be pilloried. We do not seek respectability, we seek faithfulness - faithfulness to the reality of Christ who is the Light of this age and every age, and to the Church which receives its truth from Him and the gift of his Spirit. And with that faithfulness to Christ and his Church comes faithfulness to what it is to be human and the building of a society in which everyone has the capacity to flourish whatever their race, creed, age, status and ability. The lamentation for a past time, some glorious golden age, is not a Christian song. It is not the song of faith but of despair, for our faith gives us a vision not of what has been but of what will be, whatever the difficulties or sufferings we have to endure. We cannot surrender or lose confidence in the future which God has secured for us. This is why the Church must always be an active agent in the creation and building up of a genuinely humane culture.

Let me make some simple practical suggestions which might help our secular society understand the Church and come to see it as a partner in the common good, not an adversary.

First, there is a need for the State to acquire a better understanding of the contribution and place of faith in British society. Legislation on discrimination, much of it good in itself, is now being used to limit freedom of religion in unacceptable ways. The sad and totally needless conflict over the Catholic adoption agencies is one example. But that is a symptom of a wider prejudice that sees religious faith as a problem to be contained rather than a social good to be cherished and respected, and which properly and necessarily has a public as well as a private dimension.

Second, extensive contributions made by Christian charities in the UK have been largely underestimated by the authorities. Governments would be wise to provide a greater and more autonomous role for the voluntary sector in delivering key public services. Many of these charities not only serve their own religious communities but the whole community irrespective of religious affiliation or none. I am thinking also of the excellent voluntary social work done in all the parishes of our country, without recompense but contributing in a wonderful way to the common good and social cohesion. /p>

These are two small practical aspects of what I am calling a new apologetics of presence. It is a way of keeping open a space for what is good and truly human, for the Christian life when it is lived in its beauty, generosity and depth is a life that is good; it is a life which is fully human.

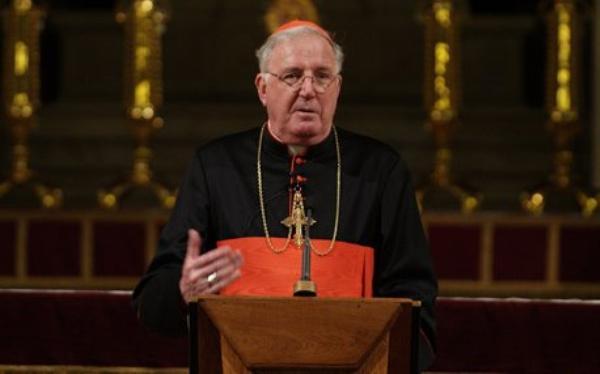

Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O’Connor is Archbishop of Westminster and President of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales.

The Cardinal’s lecture was delivered in Westminster Cathedral on 26th February 2009.

![]() Read part two of the Cardinal's lecture

Read part two of the Cardinal's lecture![]() Diocese of Westminster

Diocese of Westminster