Josef Mario Briffa SJ describes the glimpse into Byzantine life offered by the new exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts. What do the art and artefacts on display reveal about Byzantium, and what more could have been done to transport the visitor back to this bygone civilisation?

Attempting to showcase a civilisation, especially one that spanned over a millennium as did Byzantium, is bound to be equally fascinating and problematic. It is hard to be as representative as possible, while also expressing the development within a culture that, at first sight, appears so static and unchanging. Moreover, as noted by the organisers themselves, Byzantine civilisation and art have suffered from negative press given to them by western European scholars, who have considered the civilisation as decadent, and far too tied with Christianity in a theocratic system at which modern western thought cringes.

Byzantium 330–1453,the result of collaboration between the Royal Academy of Arts and the Benaki Museum (Athens), certainly lives up to the promise of highlighting the splendours of the Byzantine Empire, bringing under one roof great works from the Treasury of Saint Mark in Venice and rare items from collections across Europe, the USA, Russia, Ukraine and Egypt. The exhibition is weaved together gracefully, leading the visitor through a voyage in time while presenting major thematic blocks, from the beginning of the Byzantine empire under Constantine, through to its end at the fall of Constantinople in 1453: a time-frame that, in Western Europe, spanned from Late Antiquity right through the Middle Ages to the early Renaissance. The impact and inheritance of Byzantium in Western and Eastern Europe and beyond is also addressed.

The beginnings of Byzantium are explored through the two major figures of Constantine and Justinian. In 330 AD, a few years after the end of persecutions of the Christians and the Edict of Milan (313 AD), Emperor Constantine re-founded the city of Byzantium as Constantinople, a New Christian Rome; this date marks the start of the earlier Byzantine period, where the Eastern half was part of a larger Roman Empire, along with its Western counterpart. The treasures of this phase provide evidence of the vital link between Rome and its Eastern heir: among them the Projecta Casket [Cat. 12] with its silver embossed and partially gilt decoration portraying mythological scenes; a fragment of a marble sarcophagus from Constantinople depicting St Peter; and late Roman sculpture depicting Christian themes. A highlight of the exhibition is the Antioch Chalice [19], with its exquisite silver gilt decoration bearing vines and grapes. When discovered around 1911, probably in Syria, the artefact was believed to have been the Holy Grail, the cup used by Christ at the Last Supper. It joins a long list of contenders for this role suggested through the centuries.

By Justinian’s time (482-565 AD), the political picture is radically different: the Western Empire has long been dismembered into smaller states, as a result of both internal crises in the Western empire, and the migration of the so-called ‘barbarian’ peoples whom the Empire had previously kept at its borders. Emperor Justinian may be considered a second ‘founding’ figure of Byzantine civilisation, reconquering a substantial part of the former Western Empire, and bequeathing to the empire a revised code of law, a unified administrative system, and a single creed. A number of ivory plaques, mostly from the sixth century, provide a glimpse of the way the Emperors, such as Clementius [13], were viewed; they are portrayed using the same iconography used to depict Christ or the Virgin Mary.

Iconoclasm, with its ban on Christian figurative art and its insistence on the destruction of numerous images, proved a divisive issue for over a century until its collapse in 843, which is marked in the Byzantine church as ‘The Triumph of Orthodoxy.’ The profound theological impact and the strong feelings surrounding the end of iconoclasm find expression in two Psalters from Constantinople [50 & 51], with their parallel depictions of the crucifixion of Christ and of an iconoclast. Admittedly, as often happens, history is narrated by the victors. In the aftermath of the iconoclastic dispute, Byzantine culture experienced a resurgence of icons which led to the strong link between icons and orthodoxy, both on a level of liturgy and worship, and as a means of theological expression.

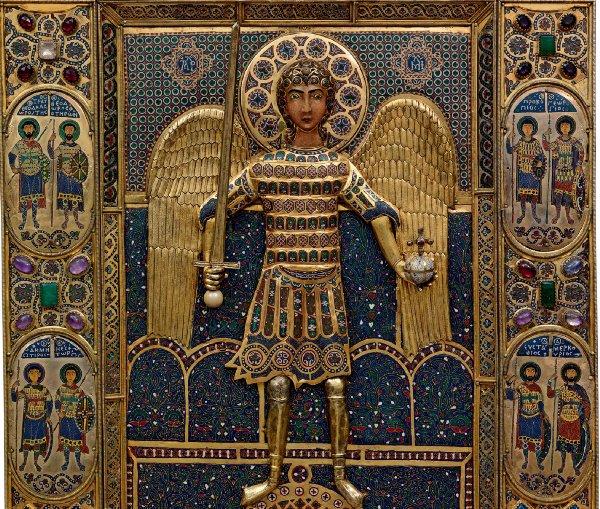

The exhibition explores three major domains of Byzantine life. The first is the Court, the centre of the political life of Byzantium and all its ceremonial happenings, centred on the Emperor. The imperial patronage of the Court, with its art serving to express majesty as well as legitimise authority, is exemplified by the ivory plaque depicting Christ blessing Otto II and Empress Theophano [70]. The twelfth century icon of the Archangel Michael [58], made of silver, gold, precious stones and enamel, rightly deserves pride of place, along with lavishly illustrated manuscripts of Psalters and Gospels [59 & 60]. A carved ivory casket from Troyes Cathedral [67], depicting emperors riding and hunting, and other decorated caskets recall more mundane aspects of courtly life, showing how the artists were still inspired by the images and text of the Classical period.

Far more could have been unlocked for the non-specialist visitor through more detailed labelling, highlighting some of the symbolism and the inscriptions. Few of the figures and scenes, both mythological and biblical, while identifiable by their symbolism and Greek inscriptions, are explained to the viewer, rendering the whole unnecessarily arcane. To mention merely one example, it is great to admire the beauty of the alabaster paten with the figure of Christ in enamel [80], but it is significant to know that inscription recalls Jesus’ words “Take and eat, this is my body” (Mt 26: 26), placing the object in its liturgical and theological context.

Moving from the Court, a healthy glimpse into the more day-to-day side of Byzantine life is ushered in, looking at the Home. The simple beauty and at times naïve decoration of domestic objects, provide a contrast with the more official and generally ecclesiastical art that dominates the rest of the exhibition. Primarily, the objects are grave goods, buried with the dead as signs of affection, of social status, and a lingering desire to give objects for the afterlife. Graves also provide a better chance of preservation, as the items are not worn out. The artefacts include not only ceramics, but metal objects and jewellery, as well as some textiles and leather ware. The decoration of a bucket [98] made of hammered, chased and punched brass, is an example of the detailed work that was invested in such mundane objects. Three examples of similar buckets have been found in Britain, an indication of the wide influence such objects had far beyond the confines of the Byzantine Empire. The fine workmanship and eye for detail emerges even more strongly in the jewellery. A child’s tunic with hood [165] and pair of sandals [166], both from Egypt and both curiously well-preserved, provide a specific glimpse into the life of children.

A final, important, domain is the Church. Understandably, icons receive ample treatment and space. An entire room is dedicated to icons from St Catherine’s monastery on Mount Sinai, icons that are very rarely available for public viewing. Other highlights include a number of examples of micromosaic work, fine mosaic work made of very small pieces of precious stones and glass: an early fourteenth century piece in two-panels (a diptych) with feasts of the lives of Jesus and Mary [227], and a two-sided icon of Virgin Hodegetria (the Virgin indicating the Way to Jesus) and the Man of Sorrows [246].

To Christian visitors especially, who know the current trend and use of icons from the Byzantine tradition in Catholic, Anglican and other churches, this would be no surprise. However, it is rather unfortunate that the importance of the icons as windows onto mystery is hardly explained, and little effort, if any, is made to unpack the significance of the symbolism and imagery that is so strongly present in them. The context, spatial and liturgical, where such icons were used is overlooked in the exhibition. The natural place of the icons is usually the church, where their positioning is significant. Their use is liturgical and devotional, linked to processions, incense, prayers and candles, not as static objects in an art gallery. This context could have been presented visually, at least through graphic illustration or the use of multimedia presentations. The rich musical tradition of Byzantium too may have enriched the canvas of presentation and provided a wider appreciation of its culture.

Byzantium 330–1453 explores the connections between Byzantine and Western Europe during the Middle Ages, and the impact this had on early Renaissance art in Italy in the 13th and early 14th centuries. A diptych of the Virgin and Child and the Man of Sorrows [247.1-2], a mid-thirteenth century work of an artist from Umbria, bears striking affinity to the two-sided icon mentioned earlier. The influence of the East on Western European art was present earlier in the Middle Ages, too, particularly in southern Europe – places like the Cathedral in Monreale in Sicily, where the architecture and especially the mosaic decorations show how far the Byzantine influence reached right into the thirteenth century. The sad chapter of the ransack of Constantinople by the Crusaders in 1204 contributed to a flow of Byzantine art to western European cities, particularly Venice (as the quantity and quality of Byzantine objects from the Treasure of San Marco attest). However, Venice did not just pillage, but also imitated the art, as in the mosaic decoration on the ceiling of the Basilica of Saint Mark, and over centuries lived in close commercial contact with Constantinople.

The more immediate inheritance of Byzantium is evident in the Christian art of the Balkans and Russia, which shows the influence and spread of distinctively Orthodox forms with Byzantine antecedents, as does the jewellery and metalwork from that region. The influence of Byzantium is also felt in the Christian churches of the former Empire, stretching from Armenia and Syria, to Cairo, Nitria (in Egypt), and Nubia (South Egypt/Sudan); the influences on all of these are represented in a selection of illustrated manuscripts of Gospels, as well as other biblical and liturgical texts [292-305]. The manuscripts are a strong reminder of the presence of minority groups and churches that have survived through centuries in a Muslim world. On one hand, this recalls the plight of churches living as minorities; on the other, the relative tolerance which allowed them to survive at a time when, in Europe, similar tolerance was unheard of.

The exhibition is certainly to be highly recommended for the works brought together here. The lavish catalogue includes essays on the history and the development of Byzantium, along with colour photographs of all the items and detailed descriptions of each. Unfortunately, the presentation of the exhibition itself presumes a certain degree of knowledge of the era. More detailed labelling and graphic presentation, as already noted, could have highlighted some of the symbolism and the inscriptions, and provided context, rendering the artefacts more comprehensible and more enjoyable. The balance leans towards the art-historical side, which no doubt deserves credit, but this points towards a missed opportunity to further unlock Byzantium as a civilisation, with its beliefs, its liturgical and religious practices, social context and its misgivings.

Josef Mario Briffa SJ is an archaeologist, and is currently reading Divinity at Heythrop College, University of London.

Byzantium 330-1453 at the Royal Academy of Arts, London

25 October 2008 – 22 March 2009

www.royalacademy.org.uk/exhibitions/byzantium

Image information:

Icon of the Archangel Michael, Constantinople, twelfth century

Silver gilt on wood, gold cloisonné enamel, precious stones

46.5 x 35 x 2.7 cm

Basilica di San Marco, Venice, Tresoro, inv. no. 16

Photo per gentile concessione della Procuratoria di San Marco/Cameraphoto