David Lonsdale explores Pope Francis’ conversations with Austen Ivereigh, which were published last year as Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future, and finds them to be rich with the fruits of a method of reflection that is closely associated with Ignatius of Loyola: discernment of spirits. How can we learn from Francis’ Ignatian approach to distinguishing what is and is not of God, especially as we seek to engage with public discourse about ‘building back better’?

The seeds of Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future[i] were planted in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic. On 27 March 2020, Pope Francis delivered an extraordinary urbi et orbi address from the steps of St Peter’s Basilica. He reflected on the pandemic in the light of the gospel story in which Jesus, in a boat with his disciples, is asleep as a storm blows up on the lake. Francis saw the world at that moment as at a turning point, facing a time of trial, from which humanity would either emerge better or go backwards. In later conversations with his collaborator, Austen Ivereigh, the pope reflected further on the crisis, its challenges, its possible outcomes and what might be done to bring about a better future. This book is the result.

Pope Francis seems to have realised early on in the crisis that the pandemic offers an opportunity for re-examining and resetting priorities and values, and changing for the better not only the daily lives of individuals and communities but also the systems, structures, organisations and institutions that sustain life for all the creatures that inhabit this planet. In the book he addresses such questions as: if you had a chance to help to shape the world as you want it to be, what would you change? Why and how would you change it? What would guide you in making those changes? What would your new world look like?

‘Discernment of spirits’ – the phrase is in the Christian tradition at least as far back as St Paul – is the method of prayer and reflection that Pope Francis chooses as his guide to shaping a better future and he invites us, the readers, to embark on a similar journey in the circumstances of our own lives. Discernment of spirits is a way of learning to distinguish between what in the world and in our lives is of God and what is seeking to frustrate God’s will (p.21). Francis sets himself a task which has three interconnected stages.

- A time to see: to use discernment of spirits to distinguish between what is of God and what is not, both in the pre-Covid world and in the contemporary world.

- A time to choose: using the same tools, to identify options and decisions which will help to shape a better world for a post-Covid future by replacing what is opposed to God’s will with what is of God.

- A time to act: to translate those options into actions that will help to embody what is of God more fully in the Church and the wider world.

The focus of this article is not so much the content of Francis’ proposals for the future as the method of discernment of spirits that Francis uses, and some of its links with Ignatius Loyola’s work on discernment.

Foundations: God, creation and grace

Two important presuppositions underpin Francis’ work in this book. The first is his belief about relationships between God and creation within the created universe, which he sums up with characteristic simplicity:

We are born, beloved creatures of our Creator, God of love, into a world, that has lived long before us. We belong to God and to one another, and we are part of creation. And from this understanding, grasped by the heart, must flow our love for each other, a love not earned or bought because all we are and have is unearned gift. (pp.13-14).

In the book he sets himself the task of setting out how all aspects of this credo can be more fully embodied in the Church and the world of the future.

Equally important is Francis’ understanding of the workings of grace in discernment of spirits. When I taught discernment to mature university students, I discovered that the members of the group who found it most difficult were the highly trained, competent, professional problem-solvers: healthcare professionals, lawyers, teachers, administrators and so on who wanted and had been trained to identify and analyse ‘the issue(s)’, find a solution quickly, apply it and move on. Discernment, in Francis’ view, calls for different dispositions. He presents us with images of God which express his conviction that the grace of God is on offer in any human situation, however dire or critical it may be. Ever-present and close is a God who, ‘by the power at work within us is able to accomplish abundantly far more than we can ask or imagine’ (Ephesians 3:20). Francis’ favourite image for this is ‘overflow’, an image of a stream or river rising over its banks to bring life to the surrounding country.

To enter into discernment is to resist the urge to seek the apparent relief of an immediate decision, and instead be willing to hold different options before the Lord, waiting on that overflow. (p.21)

The image envisages a situation in discernment in which, after prayer, reflection and honest dialogue, an apparent impasse is reached, a point at which it seems impossible to overcome the obstacles, reach a resolution, make a good choice. Francis stresses the importance in such a situation of waiting patiently on God, resisting the temptation to look for an immediate solution. It is in a time of patient waiting that ‘overflow’ happens: a way forward appears unexpectedly as a gift of grace.

Discernment of spirits

At the heart of discernment is learning to distinguish between the influences and effects of what the tradition calls two kinds of ‘spirits’, ‘the various movements produced in the soul: the good that they may be accepted and the bad that they may be rejected.’ (Spiritual Exercises §313).[ii]

Making good decisions calls for clarity about the criteria that will guide our choices. Pope Francis follows Ignatius in including ‘rational calculation’ (p.54), effectively a cost-benefit exercise:

To consider and think over rationally the advantages or benefits I would gain…and…in the same way the disadvantages and dangers…. Do the same with the alternative; look at the advantages and benefits…and conversely the disadvantages and dangers (SpExx §179-183).

Alongside ‘rational calculation’ Francis also points to specifically Christian criteria, namely the Beatitudes, unselfish service of others, and the values and principles of Catholic Social Teaching. Among the Beatitudes he highlights ‘blessed are the poor’, ‘blessed are the peacemakers’ and ‘blessed are those who hunger and thirst for justice’. One of the tests of validity of choices and actions for shaping a better future is whether they are consistent with these criteria.

This emphasis on the Beatitudes and Francis’ account of the key features of the ‘spirits’ recall two important meditations at the heart of the Spiritual Exercises. Both the ‘Call of the King’ and the ‘Meditation on Two Standards’ (SpExx §91-100 and §136-148) embody the spirit of the Beatitudes and generous service of God and neighbour. In the Call of the King, Jesus is an ‘open and kindly king’ who invites all people to ‘labour’ with him and, having done so, to share in his glory. To this Ignatius invites people to ‘respond in a spirit of love’ and to offer themselves to imitate Jesus in enduring ‘every outrage and all contempt and utter poverty’, for even in that state they may know themselves to be chosen by God (SpExx §91-100).

In the second of these meditations, Ignatius invites us to ask for the gift of discernment of spirits: ‘for the knowledge of the deceptions practised by the evil leader… and also for knowledge of the true life revealed by (Christ) and for grace to imitate him’. The contrast between the two ‘spirits’ is stark and the symbolism clear. The ‘leader of all the enemy powers’ is imagined as ‘a horrible and fearsome figure’ ‘enthroned on something like a throne of fire and smoke’. Christ, by contrast, embodies the spirit of the Beatitudes and of service. He is represented as being ‘in a lowly place, his appearance comely and gracious’. The ‘evil leader’ ‘orders’ his followers to ‘lay traps for people … to bind them with chains’ and to follow a road which leads to craving wealth and ultimately to pride. In his address, by contrast, Christ recommends his followers to ‘be ready to help everyone… to the highest spiritual poverty’, and where fitting to encourage them to follow a path that leads ‘to actual poverty as opposed to riches, to insults and contempt as opposed to worldly fame, and … to humility as opposed to pride’ (SpExx §136-146).

A complementary process in discernment is ‘interpreting and praying over events and trends in the light of the Gospel’ so as to ‘detect movements that reflect the values of God’s kingdom or their opposite’, sometimes called reading the signs of the times (p.57). As an example of this Francis highlights the global economy and in particular the distance between the need to protect and regenerate the earth for the common good on the one hand and, on the other, a global economic model that worships continuous growth at any cost (p.60). He asks whether there is an invitation here to change the global economic model radically. ‘Could it be that replacing the objective of growth with that of new ways of relating will allow for a different kind of economy, one that meets the needs of all within the means of our planet?’

This discernment step allows us to ask: What is the Spirit telling us? What is the grace on offer here, if we can only embrace it; and what are the obstacles and temptations? (p.60)

Distinguishing between the ‘spirits’

In his account of the differences between the two ‘spirits’, Francis reveals his debt to Ignatius’s Rules for the Discernment of Spirits (SpExx §§313-336), especially those in which Ignatius describes the contrasting signs and effects by which the two can be recognised. For example, he states that for those who are going forward in their love and service of God, ‘it is typical of the bad spirit to harass, sadden and obstruct and to disturb the soul with false reasoning’. The ‘good spirit’ on the other hand, will typically:

give courage and strength, consolations, tears, inspirations and quiet, making things easy and removing all obstacles, so that the person may move forward in doing good. (SpExx §315)

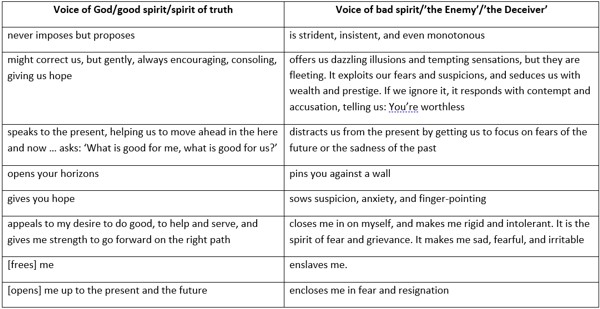

Francis refers to the ‘spirits’ as ‘voices’, which call us in different directions, speak in different languages and use ‘different ways to reach our hearts.’ (p.61) His understanding of the key differences between them can be clearly seen if we put them side by side (pp.61-2).

Applications

Francis uses discernment of spirits as a lens through which to examine and reflect on features of the pre-Covid and present world in order to distinguish what is of God from what is not. The signs of the influence of the ‘bad spirit’ are not hard to find: those systems, structures and actions which are the opposite of the spirit of the gospel and the Beatitudes. The list is long: human damage to the planet; hunger; poverty; violence; disregard for human dignity and the value of human life; injustice; exploitation and oppression by those who have power; inequalities in access to health, shelter, work, wages and the goods of the earth – all supported by ideologies, structures and institutions which benefit the few at the expense of the many, the wealthy and powerful at the expense of the poor and marginalised.

Among current trends and events in which he recognises the Spirit of God, Francis counts the generosity of the people of Bangladesh, already themselves desperately poor, towards the Rohingya refugees (p.12), and the widespread commitment of so many people to the service of others even at the risk of danger to themselves during the pandemic (p.13). There are signs of hope, too, in the cry of ‘“hunger and thirst for righteousness” … that goes up from the margins’ (p.58) and the fresh thinking of prominent economists, women in particular, about reshaping the global economy (pp.63-5). And later in the book he recalls how he has encountered in the solidarity, creative energy and capacity for radical social change among ‘the people’, and especially those who live on the margins (pp.119-122), signs of the Spirit of God.

Francis also cites his own gradual growth in awareness of the climate emergency and of the need to work for a healthy world as an example of the interior action of the Spirit of God. Ignatius wrote of the effects of the two ‘spirits’ ‘in the soul’:

With those who go from good to better, the good angel touches the soul sweetly, lightly and gently, like a drop of water going into a sponge, while the bad spirit touches her sharply with noise and disturbance, as when a drop of water falls on a stone. (SpExx §335)

Francis felt sure his growing awareness was ‘of God’ because ‘it was a spiritual experience of the sort Saint Ignatius describes as like drops on a sponge … Slowly, like daybreak, an ecological vision began growing.’ (p.31)

The Church now and in the future

As well as dreaming of a better world, Francis also addresses some contemporary issues in the Church and offers pointers towards the Church of the future that he wants to help to shape.

He finds the influence of an evil spirit in what he calls the phenomenon of ‘the isolated conscience’, for him a major obstacle to union of hearts and minds. He is referring to situations in which members of the Church set themselves up as arbiters, for example, of ‘true’ doctrine, morals, governance, practice and so on, in opposition to popes, bishops and even general councils. In response to this Francis draws on the insights into the hidden workings of evil in the human heart. In the Rules for Discernment Ignatius shows how, unbeknownst to ourselves, if we do not spot the presence of an angel of darkness disguised as an angel of light, we can be drawn progressively deeper into evil, while at the same time believing we are upholding truth and goodness (SpExx §332-335). For Francis, openness towards others is a sign of the presence of the Holy Spirit. If unrecognised and unopposed, the ‘isolated conscience’ encloses us in our own interests and viewpoints, and in the belief that we alone know the truth (p.69).

The parable of ‘Three Classes’ in the Spiritual Exercises and the notion of ‘inordinate attachments’ also throw light on this situation (SpExx §150-157). Francis suggests that hidden beneath the behaviour of an ‘isolated conscience’ is fear of losing ‘something that feeds my ego’: power, influence, security, status, whatever it may be. Fear of losing leads me to cling ever more tightly to my position, concealing my own attachments while justifying them to myself and passing judgement on others (p.70). The antidote lies in the pathway described in the Meditation on Two Standards: discernment, recognition of one’s fault, and contrition leading to humility and poverty of spirit (pp.74-75).

Francis also reflects on issues of unity and disunity in the Church in the context of discernment. In response to those who insist on uniformity in the Church, Francis points out that: ‘The Spirit always preserves the legitimate plurality of different groups and points of view, reconciling them in their diversity.’ (p.65) He also recognises the voice of a spirit of evil in polarisation and fragmentation in the Church. In response he outlines some of his longer-term plans for a genuinely ‘synodal’ Church (p.81ff), in which at every level deliberations and governance would take the form of genuine dialogue and communal discernment of spirits. His plans recall both Ignatius’s model of communal discernment outlined in the ‘The Deliberations of Our First Fathers’[iii] and the guidelines for genuine dialogue proposed by Pope Paul VI.

Transition: From a time to choose to a time to act

Francis’ guide through the final stages of the discernment process is the ‘theology of the people’, a contemporary Catholic theology recently developed in Latin America (and Argentina in particular). This theology offers a basis for translating into concrete action a vision of society that is deeply imbued with the spirit of the gospel, the Beatitudes, and other values and principles identified as being ‘of God’ through the previous stages of the discernment process.

As in earlier parts of the journey, so here Francis warns readers of likely obstacles and temptations (p.127). By way of response to them he again recalls Ignatius’s Call of the King and Meditation on Two Standards, reminding readers of the value of ‘humility and some personal austerity; this is a path of service, not a route to power … A sober, humble lifestyle dedicated to service is worth far more than thousands of followers on social networks. Our greatest power is not in the respect that others have for us, but the service we can offer others.’ (p.127)

David Lonsdale taught Christian spirituality at Heythrop College, University of London, for many years and is the author of Eyes to See, Ears to Hear: An Introduction to Ignatian Spirituality and Dance to the Music of the Spirit: The Art of Discernment.

[i] Pope Francis, in conversation with Austen Ivereigh, Let Us Dream: The Path to a Better Future (Simon & Schuster, 2020). [Page numbers in article refer to this text.]

[ii] Quotations from the Spiritual Exercises (SpExx) are taken from the translation of Ignatius Loyola’s personal writings by Philip Endean and Joseph Munitiz, published by Penguin.

[iii] ‘The Deliberations of Our First Fathers’ – the account of how Ignatius and his early companions came to make the decision that they would seek to found a religious order – can be found at The Portal to Jesuit Studies: https://jesuitportal.bc.edu/research/documents/1539_deliberationsofourfirstfathers/