O Adonai! This series on the O Antiphons promised us trauma and balm. Well there has been trauma aplenty in these last months. Trauma registers in the body’s feelings. These are my feelings and I apologise if they are not yours, which they may not be – even if you and I have been preoccupied with the same events, the odds are 50/50 that we feel differently about them. What’s more, I know these feelings don’t make an argument. But these are my feelings, mornings after, months after two trauma-inducing events among the many the world has faced this year. After Brexit and after ‘Brexit plus plus plus’, as President-elect Trump named it. (O Irony!)

The feelings are jumbled. A viscous, chill, slow shock. A broken mosaic of incredulity and inevitability. A sickly sense of lost security, of emptiness where foundations were pretending to be. A future freshly veiled over with only vaguely outlined worries. And of course there’s talk to hide behind: words, post-mortems, theories, news, all scratching an itch to distraction. And of course there are jokes, banter, wit and whistling in the dark. (O Melodrama!)

These two very different but connected political upheavals have churned in me the same set of feelings. Maybe I should be glad to have such First World Problems: it beats living among shells and shrapnel in Aleppo (‘what’s a leppo?’). (O Democracy!)

I’ve been hearing a fragment of the song Democracy from the recently late Leonard Cohen: ‘It's coming through a hole in the air/From those nights in Tiananmen Square/It's coming from the feel/That this ain't exactly real/Or it's real, but it ain't exactly there’.

That’s it. I am living in a new world and it feels not exactly real, not exactly there. Help!

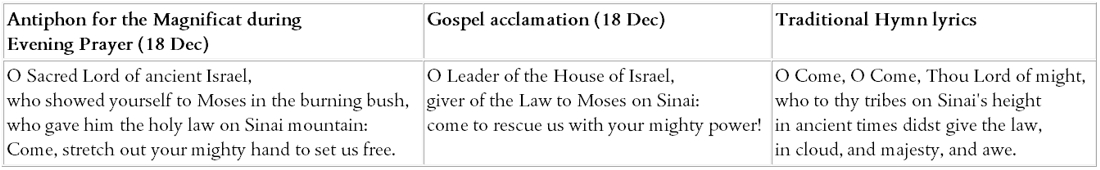

We sing the over-familiar Advent hymn till our ears ache:

O Come, O Come, Thou Lord of mightwho to thy tribes on Sinai's heightin ancient times didst give the law,in cloud, and majesty, and awe.That’s a call from the heart. O Adonai! O Lord of might. Come and fix this mess!

There seems to be something very formal about calling God ‘Lord’ — such formality sometimes signals to me that something has gone awry in my prayer, perhaps some unwanted distance has crept in if I am using this title. It reminds me of my mother calling me ‘Robert’ – I always knew I was in for it. ‘Lord’ is a name for discipline and its necessary distance. Is that who I am calling on? Come, O Come thou Lord of might? Come ‘in cloud, and majesty, and awe’. Come and put things right. Come and smite. I wouldn’t mind some well-aimed smiting.

‘Lord’ is also a euphemism. It’s a way of speaking of God without naming the unnameable. It isn’t God’s proper name: God is who God is! ‘Lord’, ‘Adonai’ affords us a necessary distance. Instead of taking to our lips The Name which written once must not be erased, we say ‘Adonai’, ‘Lord’. Calling God ‘Lord’ gives us distance, distance and height: we crane our necks to see the Lord or we cast down our unworthy eyes to avoid the Lord’s unmediated gaze.

We risk calling on Adonai because we need a saviour. We need the Might that makes Right. ‘It's coming from the feel/That this ain't exactly real…’

We have several variations on the antiphon to pray with: we’ve seen the hymn but there’s also the lectionary version and the one in the Liturgy of Hours. The antiphon in the lectionary for Mass is adds a note of euphemistic blandness:

O Leader of the House of Israel, giver of the Law to Moses on Sinai: come to rescue us with your mighty power!

It feels a little tamer and adds a little clarity. ‘Lord’ is now ‘Leader’ but the plea is the same: come to rescue us with your mighty power. But alongside Leader we now have Lawgiver. Why this reminder of Moses, of Sinai, of the Law? Why do we invoke Adonai in this context? Perhaps because we think Law brings Order, Might enforces the Law, and disorder gets punished.

O Come, O Come, Thou Lord of Might. The foundations are shaky, uncertainty is encroaching. The centre does not hold. We need a Leader. Another Leader! We need to know where we are, to whom we belong.

Has my prayer gone awry? How has this necessary distance crept in? Am I in for it now? Where is the God whose names are more intimate and tender? The God of Law and Order is some kind of answer to my trauma but it isn’t balm, it might be a tough leader for troubled times, but … my heart is not settled.

The Liturgy of the Hours says more and says better:

O Adonai of ancient Israel, who showed yourself to Moses in the burning bush, who gave him the holy law on Sinai mountain: Come, stretch out your mighty hand to set us free.

Adonai, not just of the mighty hand and holy law and Sinai’s breathless heights, Adonai who shows herself in fire that does not consume. Adonai who offers a name, a proper name, a name for unspoken whispers, a name that is not to be erased. Adonai who speaks ‘in cloud and majesty and awe’ for sure but also reveals who he is:

‘I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob. … I have seen the miserable state of my people in Egypt. Yes, I am well aware of their sufferings. I mean to deliver them.’ (Ex 3: 6-7)

Moses encounters a God of forgotten familiarity, a God of unexpected partiality, a God who hears the cry of the poor, ‘my people’. In contrast to Sinai’s Law and Order candidate, the burning bush reveals a God who comes to set us free.

Free from what? For Moses in exile maybe the answer is plain: free from his people’s slavery, free from oppression, free from Egypt. Free for a land of milk and honey (and the warfare to claim it?).

But what of us, of me? What am I crying for freedom from? Nothing so tangible as slavery or oppression, perhaps. Worry? Emptiness? Disappointment? More post-mortems? More demonisation of rival voters? It’s difficult. I know in an embarrassing way I am upset because my side lost. How could that happen? How could so many people think so differently to me? But do I want freedom from democracy? I’d better be careful what I wish for.

When the bush that burns but is not burnt catches Moses’ eye there is curiosity; when a voice speaks from it there is awe and fear; when Adonai lays out his desires Moses starts wriggling for dear life. He evades and struggles because Adonai, who has seen and heard all that is broken, intends to send Moses to do the mending.

There’s the catch in praying ‘O Adonai’: we call upon the mighty hand of God to set us free, hoping for cloud and majesty and awe, and what we hear back is ‘Yes, I already know and I already care and want you to do something about it’.

Rob Marsh SJ tutors in Spirituality at Campion Hall, University of Oxford.