Dr Timothy Howles of the Laudato Si’ Research Institute reads Pope Francis’ insights in his apostolic exhortation, Laudate Deum, as a challenge to inhabit the world in a new way. ‘We sense that something has been wrong with respect to our relationship with the earth. But if we choose to move forward and live in a different way, what world are we to encounter?’

In the 1998 comedy-drama film The Truman Show, we encounter the eponymous character Truman Burbank, as played by the actor Jim Carrey. From the moment of his birth, Truman has grown up in an artificial world, created for him by a television company, where his daily life is filmed by hidden cameras and broadcast to a global audience. Superficially, life is comfortable and secure. But Truman does not quite feel at home. Eventually he plucks up the courage to head out, sailing away towards an unknown horizon. After some time, and to his great surprise, the prow of his boat strikes a hard surface. It is a metallic wall, the great dome of the TV set in which he has lived for so many years. And so, in the final scene of the film, Truman faces a choice. Should he return to his former life and carry on as before? Or should he pass through the wall to encounter the real world that lies beyond? At stake is his future, his dignity, his very humanity.

In his apostolic exhortation Laudate Deum, released on 4 October 2023, the feast of St Francis of Assisi, Pope Francis similarly presents us with a choice. We too have an opportunity to step out bravely, if tentatively, in a new direction. But to do so we will first have to recognise that our current situation, however comfortable and secure it may seem, is an artifice. We must find a new way to inhabit our world.

Francis begins with critique of western society and its ‘technocratic paradigm’ (§20). He is referring here to the widespread assumption, which for some even has the status of ‘ideology’ (§22), that by means of our scientific, technological and economic prowess we humans have the right to extract from the earth whatever we need and, more importantly, whatever we want. Of course, the planetary boundary concept, developed in recent years,[1] shows that such a mindset cannot be upheld. The earth simply will not sustain a trajectory of endless growth. And certainly not for all people equally. To believe otherwise is, quite literally, to refuse to live in the real world.

Such a mindset can even carry through to those who are seeking to engage constructively with the environmental crisis. Take, for example, the US-based think-tank and lobby group, The Breakthrough Institute, which includes amongst its members prominent scientists and public intellectuals.[2] The Breakthrough Institute advocates what they call a ‘good Anthropocene’ strategy. The idea is that large-scale, human-devised technologies might be deployed to stabilise and reverse the effects of climate change, even as human societies continue the modes of lifestyle that have generated these harms in the first place. Thus, ‘the issue is not whether humans should control nature, for that is inevitable […] rather, we can start to think about creating natures or markets to serve the kind of world we want and the kind of species we want to become’.[3] In doing so, it is hoped that (western) patterns of consumption and growth can be maintained just as they are into an indefinite future. The Breakthrough Institute has been influential in the public policy arena in recent years, including at the highest levels of US government.[4]

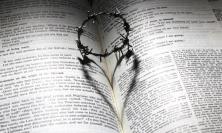

It is here that Francis invites analysis of the motives that underlie environmentalism in the contemporary world, even where good is intended. For yes, there is no doubt we have made ‘impressive and awesome technological advances’ (§28) in recent years. And surely many of these technologies can and should be deployed. But where might such a deployment conceal the need for what Francis calls ‘radical ecological conversion’?[5] Here, intentionality is what matters. For ‘not every increase in power represents progress for humanity’ (§24). Especially if the technologies at our disposal reinforce a sense that the world is nothing but ‘an object for exploitation, unbridled use and unlimited ambition’ (§25). To think this way is to see oneself as master and possessor of the earth. Indeed, to arrogate to oneself a right that is God’s alone (§73). Francis therefore calls for a reshaping of our fundamental values and orientations. By analogy with Christian metanoia, global environmentalism (in all its various forms) must seek a power that ‘transforms life, transfigures our goals and sheds light on our relationship to others and with creation as a whole’ (§61).

Perhaps like Truman, then, we too are standing at a threshold. We sense that something has been wrong with respect to our relationship with the earth. But if we choose to move forward and live in a different way, what world are we to encounter?

Here, Francis draws upon two concepts. The first is that of ‘interconnectivity’ (§57). The technocratic paradigm generated a sense of dislocation from our embedded situation in the world (what Alfred North Whitehead called ‘the bifurcation of humans from nature’).[6] We came to see the natural world ‘as a mere setting in which we develop our lives and our projects’ (§25). By contrast, we must see ourselves ‘as part of nature, included in it and thus in constant interaction with it’ (§25). Francis even alludes to the work of American ecofeminist Donna Haraway in referring to ‘companion species’, and the earth as ‘contact zone’ between human and non-human beings.[7] Of course, this is not to claim strict ontological equivalence between the two. A central pillar of the Catholic Social Teaching tradition is the absolute dignity of human life. But Francis argues that this dignity ‘is incomprehensible and unsustainable without other creatures’ (§67). For ‘the Judaeo-Christian vision of the cosmos defends the unique and central value of the human being amid the marvellous concert of all God’s creatures’ (§67). This is a sophisticated vision of theological anthropology where the telos of human existence is framed not merely in terms of autonomy, but as attentiveness to a wider set of creaturely obligations and responsibilities.

This leads to the second concept Francis calls upon, which I would tentatively suggest is that of ‘equilibrium’. To understand ourselves as interconnected with other creatures is to understand ourselves as situated within a planetary system that provides the conditions in which life can flourish. Our choices and behaviours – what we buy, what we eat, what we dispose of, where we travel, the way we occupy space – must be evaluated in terms of their potential impact on this equilibrium. Citing Laudato si’, Francis writes: ‘responsibility for God’s earth means that human beings, endowed with intelligence, must respect the laws of nature and the delicate equilibria existing between the creatures of this world’ (§62). Again, this is not reductive of human agency. For our footprint upon the earth system is uniquely impactful and risks bringing about a tipping point or disequilibrium from which it may be hard or impossible to recover: ‘we have turned into highly dangerous beings, capable of threatening the lives of many beings and our own survival’ (§28). But human agency only makes sense in the context of this wider planetary configuration. In a complex world, where the impact of our decisions can often be hard to trace, moral responsibility might take the form of asking hard questions about the extent to which we are maintaining or disrupting the delicate balance of our earth system.[8] It is finely-tuned. And highly responsive to what we do.

Just as was the case with Laudato si’ (published in advance of the Paris climate convention in 2015 and hugely influential on its outcome), this exhortation is clearly designed as a contribution to the COP28 event due to take place in Dubai in November 2023. Francis therefore offers a number of pertinent observations about previous conferences (§§44-52) and suggestions for what is to come (§§53-60).

But these practical matters are all framed by the philosophical, sociological and theological insights traced above. If the world is interconnected, and if our choices and behaviours are to be sensitive to the equilibrium of the planetary system, then a new form of politics might be possible. Here, Francis calls for ‘multilateral diplomacy’ (§41). This would be based on representation of as many as possible of the stakeholders who occupy the space of the earth, especially those who are often marginalised, and including (we might suppose) those non-human actors that don’t have a ‘voice’ at all (we must heed the ‘cry of the earth’ as much as the ‘cry of the poor’).[9] Thus, Francis calls for ‘spaces for conversation, consultation, arbitration, conflict resolution and supervision, and, in the end, a sort of increased “democratization” in the global context, so that the various situations can be expressed and included’ (§43). The global scope of the intended audience is clear, as Francis invites ‘everyone to accompany this pilgrimage of reconciliation with the world that is our home and to help make it more beautiful, because that commitment has to do with our personal dignity and highest values’ (§69).

The data is clear. The science is incontestable (§5). The time to act is now (§60). And so we stand at a threshold. Like Truman, we have an opportunity to move out in a new direction and to inhabit the world in a different way. Dare we take the first step?

Timothy Howles is Associate Director the Laudato Si’ Research Institute, based at Campion Hall, and Associate Member of the Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Oxford.

[1] See Will Steffen et al, ‘Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet’, Science 347:6223 (2015): https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/science.1259855.

[2] See https://www.thebreakthrough.org.

[3] Ted Nordhaus & Michael Shellenberger, Break Through: From the Death of Environmentalism to the Politics of Possibility (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007), p.235.

[4] For a recent study see Kristin Hällmark, ‘Politicization after the End of Nature: The Prospect of Ecomodernism’ in European Journal of Social Theory 26, no.1 (2023): https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/13684310221103759

[5] Pope Francis, Laudato si’ (2015), §217.

[6] Alfred North Whitehead, The Concept of Nature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1920), p.30.

[7] Donna J. Haraway, When Species Meet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007).

[8] For more see Timonthy Howles, ‘What kind of Thinking is needed to address the Contemporary Environmental Crisis? Reflections on the “New Political Ecology” and its relation to Theology’, Recherches de Science Religieuse 110, no.3 (2022): 503-518.

[9] Pope Francis, Laudato si’, §49.