If you’ve ever wondered about the inclusion of Jechoniah in Matthew’s genealogy of Jesus, you are in good company: none other than Sherlock Holmes has posed the very same question. In our Advent exploration of Jesus’s ancestry, alongside Pray as you go, Karen Eliasen ventures some answers. ‘Jechoniah’s inclusion in Jesus’s genealogy reminds us of God’s hand at work, even in the depth of unimaginable national disaster, to restore his anointed king and kingdom.’

The question ‘Why is Jechoniah included in Jesus’s genealogical record?’ has been asked in all seriousness by no less famous a literary character than Sherlock Holmes. It is a question which Holmes’s sidekick Watson counters with another question, as might well the rest of us: ‘Who is Jechoniah?’

This exchange occurs not in any of the original Conan Doyle stories, but in a recently published take on Holmes and Watson entitled Sherlock Holmes and the Needle’s Eye: The World’s Greatest Detective Tackles the Bible’s Ultimate Mysteries by Len Bailey. In this fanciful collection of stories, the two travel in a time machine back to ancient Israel to investigate ten of these ‘ultimate mysteries’, one being the inclusion of Jechoniah – or Jehoiachin, as he is called in the Old Testament – in Matthew’s genealogy. Questions undermining Jechoniah’s inclusion in Jesus’s genealogy centre on a text from Jeremiah in which God himself places a curse on Jechoniah: ‘Record this man as childless … for none of his offspring shall succeed in sitting on the throne of David.’ (Jer 22:30). This is a typical Old Testament scenario that seems to show God up once more as self-contradicting; elsewhere, God has made a covenant with David and his descendants that ‘his throne shall be established forever’ (1Chr 17:14). How, then, can meaningful claims be made about a Jesus who, as the Messiah, does just that: sit on David’s throne? Jechoniah, as Holmes puts it, seems ‘an intruder.’

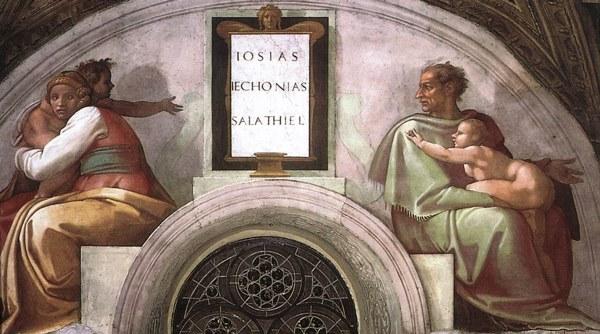

In Bailey’s story, Watson reads Matthew’s genealogy only to dismiss it with the comment that Jechoniah’s name blends in with all the others and gets lost. But this is not really true. The flow of names is broken two thirds of the way through in such a way as to make Jechoniah’s name stand out from the rest. The expected pattern consisting of a steady sequence of fathers, ‘Josiah the father of Jechoniah and his brothers, and Jechoniah the father of Salathiel’ is sliced right down the middle by a double reference to the Babylonian exile: ‘Josiah the father of Jechoniah and his brothers, at the time of the deportation to Babylon. And after the deportation to Babylon: Jechoniah was the father of Salathiel …’ (Mt 1:11-12). The name of Jechoniah, first as son and then as father, straddles not a comma but a great and terrible event; so when Matthew sums up his genealogy at the end by dividing it into three equal parts, Jechoniah’s name is left out altogether, replaced by this terrible event. Thus the three divisions run from Abraham to David, from David to the deportation, and from the deportation to the Messiah. By the time Matthew has finished covering Jesus’s genealogy, he has managed, paradoxically, both to include emphatically and altogether exclude Jechoniah’s name.

But there is a third question to be asked, in addition to the immediate who and why of Jechoniah the cursed and deported king of Judah. The story in which Holmes and Watson tackle the Jechoniah intruder mystery has a cheeky title – ‘Who’s Your Mama?’ It suggests the importance of the role of the queen mother, the gebirah, for the whole biblical royal narrative stretching across both the Old and the New Testaments. Matthew’s genealogy has a handful of women in it, including a reference to the Israelite monarchy’s first gebirah. The reference is not to a name (Bathsheba, Solomon’s mother) but simply to ‘the wife of Uriah’; then no further reference to queen mothers until we get to the very last one, Jesus’s mother, who is named: ‘Mary, of whom Jesus was born’ (Mt 1:16). In the Book of Kings all the kings of Judah, with the exception of only a couple, are listed with named queen mothers; so some curiosity about Jechoniah’s mother, sandwiched invisibly as she is between ‘the wife of Uriah’ and ‘Mary, of whom Jesus was born,’ seems called for. Although the delightfully imaginative writer Len Bailey is no biblical theologian, his three questions do hint at points of engagement with Old Testament theology that might reveal something of who Jesus’s ‘people’ are and what his kingship is about: who was Jechoniah, why is he included among Jesus’s ancestors when strictly he ought not to be, and who was his mother?

The paradox of his inclusion/exclusion in Matthew’s genealogy may reflect some unique elements of Jechoniah’s own life. These elements become more obvious when we appreciate that there are really two kings vying for designation as Judah’s last reigning king – Jechoniah/Jehoiachin and his successor, his uncle Zedekiah. They both find themselves up close and personal with the unstoppable force of history that is Nebuchadnezzar, and neither wins. But their ultimate fates are as different as day and night. Zedekiah as king (ironically made so by Nebuchadnezzar after Jechoniah has been deported) is plagued by heated debates on whether to rebel against or surrender to Nebuchadnezzar hovering at the gates of Jerusalem. In these debates, the prophet Jeremiah is on the side of surrender as a response to the tenor of the times. But when the city is finally breached, Zedekiah neither rebels nor surrenders; instead he and a few followers flee into the night, with tragic consequences. He is captured, his sons are executed in front of him and he himself is blinded, shackled and deported to Babylon, never ever to be heard of again; and the nobles with him are slaughtered (these consequences are related in Jeremiah 39).

But Jechoniah – he is the king who is heard of again! So what is his secret to the survival of his name? One thing is clear: it has nothing to do with goodness. We are told in 2 Kings 24:9 that like innumerable kings before him, Jechoniah ‘did what was evil in the sight of the Lord.’ This is not said of Zedekiah, and in many ways Zedekiah comes across as a well-intentioned king, even if a weak and dithering one. The names of these two kings vying for the honour of being considered last king of Judah contain some kernel of what is at stake here, which, as mentioned is not goodness – righteousness – per se, but rather God’s will to act. Zedekiah literally means ‘Yahweh is my righteousness’, just as Jechoniah/Jehoiachin means ‘Yahweh establishes’ or ‘raises up’. All these wicked kings that litter the Old Testament, and that Matthew lists … when all is said and done, out of their line emerges the Jesus, born of Mary, who is the Messiah, the anointed king. And the last king before this Jesus the Messiah is the one Yahweh raises up, not the one who takes Yahweh as his righteousness. What sort of king does God raise up? How does Jechoniah begin to fit this bill?

If Zedekiah’s story is that of an undiscerning rebel who does not heed the Godly tenor of the times, then Jechoniah’s story is that of someone who does heed the Godly tenor of the times – and surrenders fully to it. Only a few months after Jechoniah has become king, Nebuchadnezzar appears at Jerusalem’s gates; Jechoniah does not flee, but he does not resist either. He does not question and he does not dither. What he does do is simply actively surrender. ‘King Jehoiachin of Judah gave himself up to the King of Babylon, himself, his mother, his servants, his officers, and his palace officials’ (2Kgs 24:6-16). The Hebrew uses the simple verb ‘he goes out’, implying a plain movement; it is neither fleeing nor fighting, but nor is it waiting passively. Jechoniah goes out of Jerusalem, with his mother, with his whole retinue, to meet head on but non-violently his God-willed fate: Nebuchadnezzar.

So Jechoniah is someone who on the one hand does evil in the sight of God, but on the other hand, when push comes to shove, surrenders to that same God’s will. Perhaps hidden in that conundrum is an insight into Jechoniah’s inclusion/exclusion in Jesus’s genealogy. As we learn at the very end of both the Second Book of Kings and the Book of Jeremiah, Jechoniah’s story surprisingly does not end with the surrender of an evil king of Judah to Nebuchadnezzar. Further down the timeline, after deportation and prison, Jechoniah finds his personal fortunes changed for the better. If he is cursed at the height of his kingship in Jerusalem, he is blessed at the end as a king in exile in Babylon. Although Jechoniah is deported and imprisoned (this is related in 2Kgs 24:6-16 and in 2 Chr 36:9 ff), at some later stage he is released from prison and given a generous lifestyle at the Babylonian court. ‘So Jehoiachin put aside his prison clothes, and every day of his life he dined regularly at the king’s table.’ This fairy tale ending, reminiscent of the ending of Job, is a restoration of sorts and certainly a glimmer of a fate that hints at God’s generosity, quite in contrast to the frightening fate of the resisting, bereaved, blinded, shackled and forgotten Zedekiah – one could be excused for thinking Zedekiah rather than Jechoniah is the cursed one here. All is not hopelessly lost, even if Jerusalem and its temple have been destroyed. Rabbinic tradition makes much of this hope in the midst of seemingly total loss, and of what might have changed Jechoniah’s fortunes from an evil king in a besieged Jerusalem to a comfortable and well-respected king-in-exile in Babylon. The rabbis surmise that his sad experiences changed Jechoniah’s nature entirely, to the point where he repented of his sins as evil king. In the Old Testament, human repentance is of course the key to many a change of heart of God’s.

However we are to understand Jechoniah’s unquestioning surrender to Nebuchadnezzar, and the meaning of this act within the whole king narrative from David to Jesus, at play may be a gender theme to do with queen mothers. It is hard not to associate surrender with a certain feminising, and the presence of the queen mother in a king’s life as feminising. Mary’s ‘yes’ to Gabriel gives a focused slant to that question of all origin questions, ‘who’s your mama?’ to which Jesus might answer: the one who surrendered completely to the power and might of God (the Hebrew root gbr which means ‘strength’, as in hunter or warrior strength, gives rise both to Gabriel’s name and to the queen mother title, gebirah). Given Jechoniah’s penchant for surrender, it should come as no surprise that his mother (her name is Nehushta, meaning ‘serpent’, as in Moses’ bronze serpent called a nehushtan) makes brief but emphasised appearances in the Old Testament. The description of Jechoniah’s deportation is repeated three times (2Kgs 24:12 and with slight variations in v15, and then again in Jer 29:2), and what is immediately obvious in all three renderings is that the mother is listed right after the king. She, too, is surrendering and being deported. An indirect allusion to Jechoniah’s deportation appears also in the prophecy in Jer 22:26: ‘I will hurl you and the mother who bore you into another country, where you were not born, and there you shall die.’ These events do not happen to Jechoniah alone, but to Jechoniah and his mother. Queen mothers in the Old Testament tend, like its kings, to ‘do evil in the sight of the Lord,’ but we know nothing of what Nehushta was actually like. What we do know beyond a shadow of a doubt is that she went out of Jerusalem with her son the king to surrender to Nebuchadnezzar, that she was deported along with him to Babylon, and that this fact is somehow relevant in the bigger scheme of things.

These observations only touch the tip of the iceberg of this bigger scheme of things. Jechoniah may at first glance appear as an ‘intruder’ in Jesus’s genealogy, but his particular experience of and response to the deportation to Babylon tell us something about what it means to be a Davidic king, to be a son of David – a Solomon at the beginning, a Jechoniah in the middle, and a Jesus at the end, three kings with powerful queen mothers, and each a marker for a different phase. Jechoniah’s inclusion in Jesus’s genealogy reminds us of God’s hand at work, even in the depth of unimaginable national disaster, to restore his anointed king and kingdom.

Karen Eliasen works in spirituality at St Beuno’s Jesuit Spirituality Centre, North Wales.

Read more:

5. Zechariah, Elizabeth and John

For further reflection, try Pray as you go’s Advent retreat, ‘All the Generations’. Listen >>