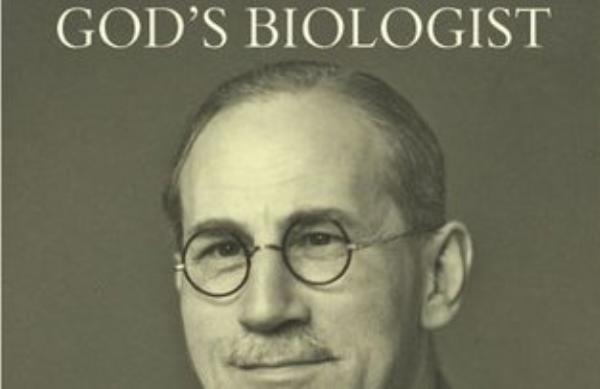

This book might almost have been entitled, ‘From Plankton to Prayer’. Bizarre, to be sure; but one does not often come across someone who is an expert in the biology of oceans and the relationship between plankton and the movements of fish, and who also has a deep interest in the relationship between the theory of evolution and research into religious experience. Such a man was Alister Hardy. He did oceanographical research on board little fishing boats from Hull, as well as on the Royal Research Ship, Discovery deep in the Antarctic. He held professorships in Biology in Hull, Aberdeen and Oxford. Yet the more complex depths of his character came from an important experience he had as a schoolboy at Oundle, which he describes as follows:

There is no doubt that as a boy I was becoming what might be described as a nature mystic. Somehow, I felt the presence of something which was beyond and yet in a way part of all the things that thrilled me…..Just occasionally, when I was sure that no one could see me, I became overcome with the glory of the natural scene, that for a moment or two I fell on my knees in prayer – not prayer asking for anything, but thanking God, who felt very real to me, for the glories of his Kingdom and for allowing me to feel them.

That this was not a passing phase can be seen from something he wrote about the end of his first term at Oxford in 1914, just before he joined the Army:

During the term, I had become more and more convinced of the importance of bringing about a reconciliation between evolution theory and the spiritual awareness of man, At the end of the term I made a most solemn vow; it wasn’t actually in the form of a prayer, but I vowed to what I called God that if I should survive the war, I would devote my life to attempting to bring about such a reconciliation that would satisfy the intellectual world.

Hardy’s effort to live out that vow is, in David Hay’s view, the key to his whole life. To many of his contemporaries, though not to his wife, this might have been less than obvious for most of the forty years after the First World War, during which his career progressed from Hull to Oxford. Hay, however, mentions papers, now preserved in the archives of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, which include brief notes to himself as well as sketchy projects for possible books. From these papers, in Hay’s view, we can see that Hardy’s vow was still very much alive. The project surfaced explicitly, once in his inaugural lecture in Aberdeen in 1942, but in its full form in 1962 when, to many people’s surprise, Hardy was chosen to give the highly prestigious Gifford Lectures. The appointment required the lecturer to:

…treat their subject as a strictly natural science, the greatest of all possible sciences, indeed, in one sense the only science, that of Infinite Being without reference to or reliance upon any supposed special, exceptional, or so called miraculous revelation. I wish it considered just as astronomy or chemistry is.

The emphasis on scientific method, and the distancing from any particular religion suited Hardy well; he claimed that he was an Anglican in his heart, but a Unitarian in his head.

The last quarter of this book consists in a discussion of the role Hardy’s project played in the latter years of his life. By then, there was a widespread assumption that a commitment to scientific method automatically excluded the possibility that there might be any truths which that method could not reach. So his founding of the Religious Experience Research Unit tended to find little sympathy both with Anglicans and with the Unitarians who saw the project as threatening their religious beliefs, and with many scientists who assumed that religious experience was perhaps a strange sociological phenomenon to be studied as such, but certainly not the source of any kind of truth about the universe. Hay himself became the Director of the Research Unit in 1985 and is very well placed to give an account of the many controversies in which it was perforce involved. Two perhaps stand out: the first is the difficulty in determining exactly what the term ‘religious experience’ should be taken to include and whether, once a workable way of delimiting the field has been achieved, it can be shown that having such experience is a natural product of the evolutionary process, rather than some culturally conditioned projection of human needs; and the second major issue is whether such experience involves an awareness of a transcendent entity of some kind.

Hay’s account of this nest of controversies contains many striking examples. He is in broad terms very sympathetic to Hardy’s views and, it seems to me, does enough to help the reader to have at least some inkling why they must be taken very seriously. But the relations between evolutionary theory, the various sciences, theology and religious experience are extremely complex, and this part of the book, in which the key to Hardy’s whole life is finally in full focus, does not make for easy reading. However, David Hay is writing a biography, not a textbook on the connections between evolutionary theory and religious epistemology. He has offered an attractive portrait of a man who had both the technical competence and the personal courage to challenge some of the most entrenched prejudices of his, and our, time. In so doing, he has shown the kind of integrity and attention to detail which will be required if we are to give our own answers to Hardy’s questions.

The reviewer, Gerard J. Hughes SJ was head of the philosophy department at Heythrop College, University of London, and is currently tutor in philosophy at Campion Hall, Oxford. He is the author of Aristotle on Ethics, Is God to Blame? and Fidelity without Fundamentalism (DLT, 2010).

![]() Find this book on Darton, Longman and Todd's web site

Find this book on Darton, Longman and Todd's web site

![]() Shop for this book on Amazon, giving a 5% cut to the Jesuit Refugee Service, UK

Shop for this book on Amazon, giving a 5% cut to the Jesuit Refugee Service, UK