‘Fasting as a ritual act is not merely a symbol or a metaphor for some other-worldly activity. It is an experience of concrete, this-worldly changes.’ Karen Eliasen looks to the wilderness narratives of the Old Testament to explore how the physicality of fasting forms a part of God’s ongoing dialogue with his people.

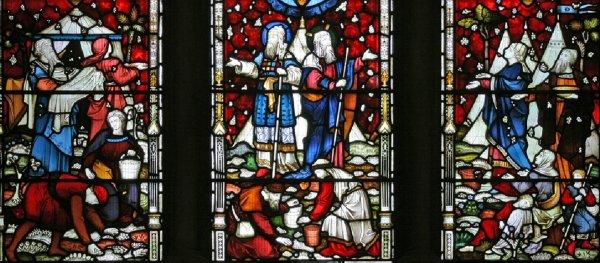

We are moving towards the end of the great fasting season of the Church, a season whose tumbling blend of ashes, repentance and promise taps into an ancient biblical world of ritual and tradition familiar to readers of the Old Testament. Many different contexts, invariably to do with loss and fear, appear in the Old Testament narratives where God’s faithful are urged to, ‘change our garments to sackcloth and ashes, fast and weep before the Lord,’ (as the first Lenten Antiphon has it). Dishevelled hair, torn garments, even gashed skin and self-mutilation, can take these actions, ritual and otherwise, to a severity well beyond having one’s forehead smeared with ash and saying sorry. But this severity is discouraged within the Old Testament. ‘Do not cut your bodies for the dead,’ says the Lord in Leviticus 19:28. Drawing one’s own blood is the sort of thing the prophets of gods other than Yahweh resort to, as we see the prophets of Baal doing with swords and spears in the great fire competition with Elijah (1Kings 18). Drawing blood may seem as extreme, life-threatening even, as ritual action can get. Nonetheless, in the Israelite religious imagination there is something about drawing blood that is recognised as a vital constituent of the dialogue between God and Israel. In Leviticus, the ritual focus is on animal blood rather than human blood. After the destruction of the Second Temple, all this ritual activity takes place in the imagination of the Torah reader. Fasting, however, remains a real practice, not an imaginative one – although surely it cannot be denied that stopping eating is a life-threatening action no less so than gashing the skin and drawing blood. Fasting as a ritual act is not merely a symbol or a metaphor for some other-worldly activity. It is an experience of concrete, this-worldly changes. It is literally an experience of starvation in which the body experiences itself beset by potentially life-threatening physical changes as it starts to feed and nourish itself on itself. What are these real physical changes meant to communicate within the dialogue carried on between God and Israel?

We might for a start gather some clues about fasting from the ritual sacrifice language of Leviticus. We might enter into that world of blood-drawing imaginatively, as the early Torah-reading rabbis did. The 4th century Talmudist Rav Sheshet puts it as concisely as it can be put. After his penitential fast, Rav Sheshet prayed ‘that my fat and blood which has diminished through fasting be as if I sacrificed them on the altar before you, and you favoured me with forgiveness’. These may not be unfamiliar theological sentiments. So well-established is the close tie between fasting and serious religious activity in most people’s minds that it may come as a surprise to realise that although fasting as such is often urged and described within the Old Testament, it is only legally prescribed on one particular occasion; and even there it is not explicitly fasting as such that is being insisted on, but rather a self-affliction of some sort. The legal text in question appears in the middle of Leviticus 16, the chapter that details the ritual ‘do’s and ‘don’t’s for the celebration of Yom Kippur, the great Day of Atonement so central to Jewish worship. Not coincidentally, this chapter is launched with a brisk reminder of what has already happened to Aaron’s two older sons during their ordinations ‘when they drew near before the Lord’: they died (see the perplexing story of Nadab and Abihu in Leviticus 10). The chapter continues with a set of legal prescriptions for the scapegoat ritual by means of which atonement for sins is made by the High Priest on behalf of all Israel and for the sanctuary itself, with a couple of dire warnings thrown in: ‘or he will die.’ Drawing near before God may be atoning and life-renewing, but it is also risky and can in the blink of an eye prove life-threatening. One of the ritual precautions for this Day of Atonement, fraught with danger as it is, involves fasting. Everyone – the High Priest, all of the Israelites, and all of the aliens dwelling among them – are subject to this ‘for ever’ commandment: ‘In the seventh month, on the tenth day of the month, you shall deny yourselves …’ (Leviticus 16:29). Or at least, ‘deny yourselves’ is how the NRSV and many other versions have it. The NJB simply has ‘you will fast’, which is also how Judaism subsequently through the centuries has understood the Leviticus commandment. But what does this phrase actually entail?

It is the King James Version that probably comes closest in translation to the original Hebrew phrase: ‘ye shall afflict your souls’. The translation ‘afflict’ rather than ‘deny’ reflects an element of active violence present in the original Hebrew verb ‘ana , whose primary meaning is to ‘try to force submission through inflicting physical pain’. The verb does appear directly in tandem with the act of fasting in Psalm 35 when the psalmist says, ‘I wore sackcloth, I afflicted myself with fasting’, but here in Leviticus 16 the usual word for fasting itself is left out. Elsewhere in the Old Testament, ‘ana occurs in quite different contexts. It is used to describe anything from Sarah’s treatment of the hated Hagar (Genesis 16:6) to Egypt’s enslavement of Israel (Exodus 1:11), and even to one army’s brutal subjection of another in war (Numbers 24:24). It is the kind of behaviour God warns Israel not to indulge in towards ‘the widow or the orphan’ under threat of death (Exodus 22:22). It is also the kind of extreme behaviour that the psalmist skirting death accuses God himself of: ‘Your wrath lies heavy upon me, and you overwhelm me with all your waves’ (Psalm 88:7). ‘Overwhelm’ is the choice of the NRSV, but the King James again sticks with ‘thou hast afflicted me with all thy waves.’ But most unsettling of all is how Moses applies this ‘ana verb, with all its connotations of physical violence, to how God behaves towards his own people wandering in the wilderness. Moses reminds Israel in Deuteronomy 8:16 that God, ‘fed you in the wilderness with manna that your ancestors did not know, to humble [‘ana] you and to test you, and in the end do you good’.

This recurring Deuteronomist theme of God ‘humbling’ his people through physical affliction might give us a glimpse into what underlies Old Testament fasting practices. An enslaved Israel escapes from Egypt only to find itself wandering in that ‘great and terrible wilderness’ for forty years in a state of near-starvation. Manna is all very well and miraculous, but the awful truth remains that the wilderness experience ends in death for almost the whole adult generation that originally escaped from Egypt, including Moses himself; only Joshua and Caleb make it through to the Promised Land. The story of the spies in Numbers 13-14 offers an explanation for so many years of wandering – people become frightened of ‘falling by the sword’, and refuse to rely on God who in turn becomes angry enough to keep them wandering. The wilderness narratives seethe with hot-headed mutual recriminations between God and Israel, and the story of the spies hints at what may lie at the heart of what human beings hold against God and what God in turn holds against human beings. ‘How long,’ fumes God in Numbers 14:11 (and far from the first or last time) ‘shall this wicked congregation complain against me?’ But the ‘complaining’, or as the King James version understates it, ‘murmuring’, is often accompanied by a loud weeping and wailing and tearing of garments – which is very naturally what frightened and hungry human beings resort to. In these desperate circumstances, any long-term hope for freedom and shalom is completely overridden by the immediacy of fear and hunger: ‘If only we had died by the hand of the Lord in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the fleshpots and ate our fill of bread; for you have brought us out into this wilderness to kill this whole assembly with hunger’ (Exodus 16:3). And: ‘Would that we had died in Egypt … Why is the Lord bringing us into this land to fall by the sword?’ (Numbers 14:3). Yet it is in the context of these concrete near-death experiences, these afflictions, that Israel finds itself drawing piecemeal closer towards God, closer towards Sinai, and closer towards the receiving of the Torah – paradoxically, the Torah at the heart of whose ritual activity beats the Day of Atonement with its commandment to, on that day, ‘afflict your souls’.

The wilderness wanderings are paradoxically double-barrelled. One barrel points at the intimacy of the encounter between God and Israel at Sinai, where what is imagined happening is the kind of intimacy that inspires Jewish liturgical tradition to place the complete Song of Songs within the Passover celebrations. It is as close, as intimate as two separate entities can get, and it is fraught alike with the potential for new life and the threat to life itself. This is the sort of link between the erotic and the fatal the midrashic tradition in Judaism excels at making. That a love-book brimming with shalom and food metaphors should be read in conjunction with ritually remembering a wilderness experience characterised not by peace and plenty but by violence and starvation, is a classic example of the utmost seriousness with which the midrashic mindset explores paradox. This violence and starvation is what the other barrel brings into perspective; it is a perspective which sees the wilderness wandering as a period of deep-rooted unfaithfulness and rebelliousness against God. This rebelliousness has an existential quality to it that emerges from real experience. Not death itself as such, but death by war and by famine; embodied life potentially entails great afflictions and consequently great fears, made all the more paradoxical in that this vulnerable, embodied life is God-given. Are these afflictions punishments for disobedience to God, as the Deuteronomists and much Prophetic poetry surmise? Or are they built into the very fabric of God’s creation, as both Wisdom literature and Priestly material sometimes seem to hint at? The extraordinary thing is that, even as they are caught in a vicious circle of mutual recriminations about the origin and purpose, even nature, of ‘afflictions’, God and Israel somehow remain in dialogue with each other as they fleet in and out of each other’s immediate company on the wilderness trek. This dialogue, this encounter, and the commitment to continuing it at all costs, is for ancient Israel especially played out in the ritual activity of the sanctuary, and there above all on the Day of Atonement, the one time at which Israel is commanded to fast, to voluntarily ‘afflict their souls’.

Afflicting our souls, diminishing our ‘fat and blood’ – as fasting Christians we may not as readily as Rav Sheshet imaginatively engage with the sacrificing High Priest entering the innermost part of the sanctuary on the Day of Atonement to be ‘humbled’ by God. But we may try to take to heart the insistence in Hebrews 10:19 that, ‘we have confidence to enter the sanctuary by the blood of Jesus, by the new and living way that he opened for us through the curtain (that is, through his flesh)’. So for us too, it is ‘as if’ we draw closer and closer to God, and discover in our dialogue with him about the human predicament that instead of being punished with death we are favoured with forgiveness. And thus assured in the face of fear and hunger, we can move closer still to the full Easter experience.

Karen Eliasen works in spirituality at St Beuno’s Jesuit Spirituality Centre, North Wales.