Friday 15 June is the Feast of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, a devotion that inspires many Catholics but from which others shy away. Dermot Power encourages us to be sensitive to the truth about God’s love for us that this feast can help to illuminate.

The Sacred Heart as a devotion has for some time suffered a mixed press. The Irish priest and commentator, Brendan Hoban, sees in it a passivity which leads to a spirituality with some negative pastoral consequences.

My own early memory of the devotion to the Sacred Heart comes from my Catholic, London Irish, Angela’s Ashes upbringing and is bound up with my fear of the dark as a small child. Outside of the little bedroom I shared with my brother, there was an old-fashioned, tiny night light attached to a rather battered and old picture of the Sacred Heart. This light was just enough to see me through the night and assuage my fear. In the midst of the violent and harsh environment around the streets of Notting Hill, where Irish and West Indian immigrants lived in tenements overseen by the notorious landlord Rachman, whole families living in just two rooms, I remember being touched at some primal level by the light and the image of a tenderness that I associated with God. Somehow I knew that God had his heart aches too, which wasn’t such bad Christology for a 7-year-old!

The sentimentality, the soft, even effeminate image of Jesus, bordering on the kitsch, can often be an affront to Catholics of high culture and even those of biblical sensitivities. Like its cousin, the devotion to the Divine Mercy, it raises liturgical blood pressure if it manages to invade the sacred spaces of altar and ambo.

I can understand completely why the kitsch dimension cannot be overlooked by many, for it can interfere with the original, creative struggle or sacrifice that is associated with true art. However, we need to remember that it is what people project onto the mass-produced kitsch that must be respected. People who do not have high culture or access to its special world are often people who suffer very deeply. They have a wisdom and refinement which is cultivated in the crucible of having to live at a very profound level, and they can find some identification with an image such as the Sacred Heart. Liberation Theology in the last two decades has had to look again at its assessment of popular religion in the light of its own insistence on ideological purity. We need to learn to walk more carefully in this world of the Sacred Heart, Divine Mercy and images and relics of the saints, lest we tread on people’s dreams.

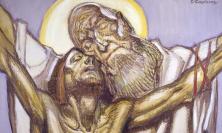

Karl Rahner, no less, saw in the devotion to the Sacred Heart a very profound way of expressing truths about the incarnation and affirmed its deep biblical foundations. For him, the Father’s giving of his eternally begotten Son, the gift of a human heart, is a radical statement of the very heart of the Christian faith itself. Without leaving his own side, in the incarnation God comes over to ours. This is echoed in the Gospel of John when we hear that God so loved the world that He gave His only Son, not that the world could be condemned but that the world could be saved. The breaking open of the body of Christ on the cross, the lance that pierces his side from which flows blood and water, is for a Christian theological imagination the outpouring of triune love into a broken and tragic world. At the heart of the world is the broken heart of God and vice versa. In Servants of the Lord, Rahner suggested that the Church in the West would lose much of its status and its value, and experience great vulnerability and frailty. In the sixties when he wrote this he called it the ‘Church of Tomorrow’, which really is our ‘Church of Today’. For him this future vulnerable community of faith would need to find its roots again and have its authenticity mirrored in the image of the Man with a wounded heart.

In the words of another theologian, John Farrell OP, the Christian, the Church, its ministry is to be the poet and prophet of Golgotha, to communicate love at the very heart of a world that does not know it is loved.

In a funny old way, many of the sugary hymns of my own youth, particularly those of the Sacred Heart, captured this dimension of unrequited love: somehow, our not being able to love back intensifies in God his wanting to love us. However sentimental this might sound to our ears, if we were to listen in between the lines, like Rahner, we would hear echoes of the prophet Hosea and the longing in Jesus Himself for us to allow Him to love us better. As one of my lovely old parishioners, in Kings Cross, a widow in her eighties who had buried her only child, used to say to me, ‘Father, thank God for the Sacred Heart of Jesus’. Sounds like sound theology to me.

Rev Dr Dermot Power is Spiritual Director at Allen Hall, the Seminary of the Diocese of Westminster.