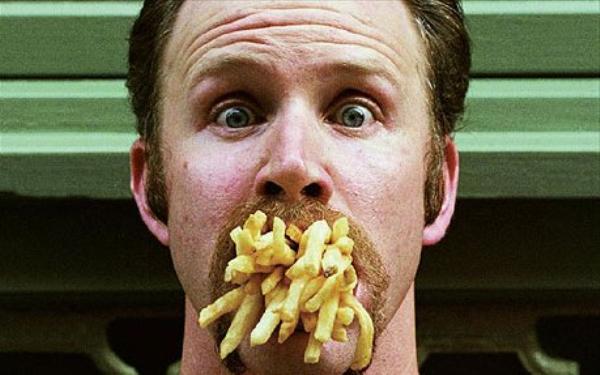

In his 2004 film, Super Size Me, Morgan Spurlock documents his experiment of eating only McDonald’s food for 30 days. This film does showcase the sin of gluttony, argues James Hanvey SJ, but not necessarily on the part of the consumer. The penultimate article in our Lenten series uncovers the reality behind the many guises that gluttony wears and the flaws in the ‘logic of excess’ on which it thrives.

There are many images of gluttony. Within the classical canon of painting stands Hieronymus Bosch’s depiction of the seven deadly sins and the four last things. He painted in the great medieval tradition of seeing the seven deadly sins as a commentary on daily life. In the paintings of Fra Angelico’s Last Judgement, it is clear that even cardinals, popes and emperors are not exempt either from the sins or from the judgement they attract.

Bosch depicts gluttony in terms of figures engaged in over-eating, absolutely filling themselves way beyond what their bodies need or indeed might actually enjoy. It is irrational excess and, as with the other seven deadly sins, a surrender to instincts which degrade our human nature. It is not surprising that Bosch manages to insinuate an animality into his figures. Nor is it surprising that even though the images are exaggerated, we can still imagine that we are looking at scenes from daily life: the expressions, gestures, grasping and cunning, they are all there. Perhaps Bosch gives us a clue: the ‘deadly’ sins are not rare; they are to be witnessed in the humbler routines of our daily lives – just look around you!

What Bosch and his contemporaries accomplished for his age, so modern cinema does for us. We normally associate gluttony with food but it can be that uncontrolled desire for excess in anything: excess for the sake of excess. While out for a meal, have we not wondered if we might just be about to see a figure like Mr. Creosote from Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life? After some spectacular projectile vomiting he manages to blow himself up with a final After Eight mint. The film Seven offers a particularly vivid and disturbing image of gluttony: a massive, sauce-spattered figure lies face down in a plate of spaghetti and vomit, flies buzzing around his swollen head. He has been forced to eat until his intestines ruptured, a human foie gras. That fatal excess, though in most cases not so gruesome, is everywhere: you see it in the whole phenomenon of ‘bling’, vulgar excess which has no purpose but to be excess. Excess has the appearance of being intoxicating; an unrestricted freedom to indulge. That is the great illusion. Excess is deadening and that is what the deadly sin of gluttony signifies: it eats up life, body and soul. On the surface, Morgan Spurlock’s film documentary, Super Size Me (2004) looks like a straightforward exposé of the fast food industry, especially McDonald’s. Obesity is presented as the physical manifestation of the problems inherent in the industry, but obesity is not necessarily gluttony. Obesity may be the result of many factors: it may indicate some sort of deficiency or addiction; gluttony requires a deliberate intention to seek excess. Although the glutton may appear out of control there is a willful decision behind their behaviour. In some way it is an exercise of power, a demonstration of ego, a refusal to accept restraint or to restrain.

After three days of his experiment of eating only McDonald’s food, we see Spurlock vomiting out of his car window. It is a vivid image of the body’s protest; it represents a craving for the healthy option. But despite the increasing damage to health and mind, he sees the experiment through to the end. In the course of 30 days – the length of the experiment – we also learn a lot about the power of the fast food industry, and about people and the way in which we are all shaped by contemporary culture. There is also an enormous medical and human problem that is being built up for the future, a future that the American Health Insurance Industry will no doubt find very lucrative, whatever the cost may be in terms of human suffering. Super Size Me ends with no surprise: Spurlock has been eating himself to death and the quality of his life has declined. Indeed, the Big Mac is addictive and if this were not an ‘experiment’ one wonders if Spurlock’s only comfort would not be the food itself. Fast food is not food, it is a way of life, a way of comfort whether one is rich or poor.

Super Size Me is about gluttony, but it would be a mistake to think it is about the people who are eating fast food. To be sure, they may be culpable, at some level they all know the risks; but they have been enticed cleverly and deliberately into the web. Even children are ‘groomed’ to associate fast food with pleasure and good memories. The sin of gluttony lies with the companies and the market systems. It is they that devour people.

In recent years we have all seen the effect of these market systems. The logic has been impeccable and we have all been ‘Super Sized’. It little mattered that the actual product was toxic; all that mattered was the profit margin. There is no rule for how big a profit margin should be except ‘as big as it can be’. What does excess mean in this context? Excess only makes sense when it is measured against standards and values which represent reason, and measures of genuine need; it needs to be measured against a good or a mean. I only ‘need’ 2500 calories each day, not 6000. I only ‘need’ to earn x amount for a reasonable, secure life not x + millions. So what takes over? Under the guise of being in control and making choices I find that I am driven only by the momentum of excess. Excess becomes its own reason or logic. When excess becomes its own end, it is destructive of my life, my relationships and my happiness and, often, the happiness of others. Gluttony has no sense of responsibility; it does not acknowledge that it owes anything to anyone. But it would be a mistake to think that it is chaotic. It can be quite systematic and ruthless in its pursuit of its own excess. We find this in many systems and it is this hidden ‘logic’ of gluttony which Super Size Me uncovers in the callous, driven industry of which fast food is only one example. The market is not just about meeting needs, it is about creating them. The consumer society makes us consumers under the illusion that in the ‘Super Size’ we are actually getting something extra, that we are beneficiaries. Gluttony is not always gross; it does not always reveal itself in the grotesque or animal feeding frenzy. It can be quite clever, well-dressed, slim and sleek, enjoying a sophisticated life and tastes, but utterly rapacious. It does not see people; it only sees bodies, minds, souls to feed up.

Spurlock’s experiment was designed for 30 days. There is an alternative 30 day experiment: it is called the Spiritual Exercises of St Ignatius of Loyola. The whole point of these exercises is how to free myself from illusion and inordinate attachments; to grow in self-knowledge, freedom, love of God and love of neighbour. What better way to detoxify body and soul and discover a healthier way of living?

Rev. Dr. James Hanvey SJ lectures in Systematic Theology at Heythrop College, University of London and is Superior of the Jesuit Community at Mount Street, Central London.