As our Lenten journey nears its end, Fr Jack Mahoney concludes the series in which he has helped us to ‘Keep Lent with Saint Luke’. The fragmented stories of the appearances of the risen Christ that we read in Luke’s Resurrection narrative and other New Testament accounts, point us beyond the excitement of the disciples to the joyful heart of our faith. In our celebrations this Easter, the Lord says to us: ‘I have risen and I am still with you’.

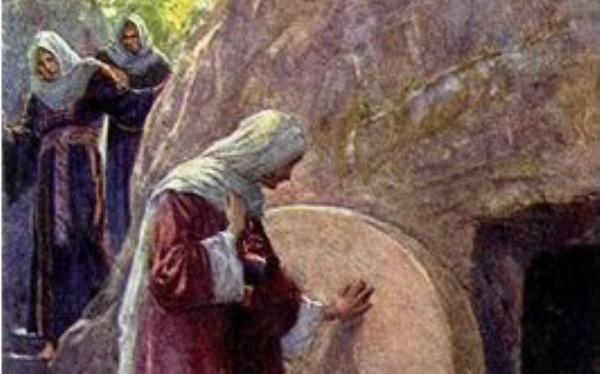

The painting of the empty tomb(shown here), for which I am indebted to the website of the Mormon Worker, captures beautifully the beginning of St Luke’s account of the Resurrection of Jesus (24:1-12). After Jesus died on the cross, according to Luke following Mark’s earlier version, a secret follower and member of the Jewish council, Joseph of Arimathea, secured the release of Jesus’s body and laid it in a tomb hewn out of the rock (Lk 23:50-53), rolling a large stone against the door of the tomb to seal it. Luke adds that ‘the women who had come with him from Galilee followed, and they saw the tomb and how his body was laid’ (23:55), but since the Sabbath was now beginning ‘they rested according to the commandment’ and ‘prepared spices and ointments’ (23:56) so that they could return after the Sabbath to anoint the body of their Lord.

‘He is not here, but has risen’

The picture shows three of the women followers of Jesus making their way to the tomb ‘on the first day of the week at early dawn’ (24:1-2), two older women cautiously feeling their way down the rock steps through the garden, with a younger woman, no doubt Mary Magdalene, having led the way and standing at the entrance to the tomb in the rock face. She has a hand reached out questioningly to touch the large round stone, which had evidently been rolled back from the doorway, leaving the tomb with an air of emptiness which she appears about to explore. Luke says of the women (24:3) that ‘when they went in, they did not find the body’, to their bewilderment. But suddenly to their added terror they became aware of two men in dazzling clothes standing just beside them. These figures asked them, ‘Why do you look for the living among the dead? He is not here, but has risen’ (24:4-5). The men went on to remind the women that when Jesus had been in Galilee with them he had foretold that he would be put to death and would rise from the dead on the third day (24:6-7). ‘Then they remembered his words’, Luke continues, ‘and returning from the tomb, they told all this to the eleven and to all the rest’ (24: 8-9).

The remainder of this brief opening section of Luke’s account goes on to identify the women who reported their experience of the empty tomb back to the apostles ‘and to all the rest’, describes how their news was dismissed by the apostles as ‘an idle tale’, and tells (in most manuscripts) of how Peter then ran to the tomb to check for himself and found it empty, and ‘went home’ at a loss to what had happened (24:10-12).

This concludes the gospel passage from Luke for this year’s Easter Vigil, leaving us hanging in the air, and dissatisfied, as I think we can sometimes be at the gospel passages selected for Sunday Mass. However, Luke’s full account of the Resurrection of Jesus, his whole 24th chapter, is more substantial, and contains the famous story of the meeting and conversation between the risen Christ and his two dejected disciples whom he sought out on the way to Emmaus, a typical instance of the good shepherd collecting his scattered sheep together (24:13-33). As soon as the two disciples recognised Jesus at supper from the way in which he handled the bread, and he ‘vanished from their sight’ (24:30-31), they rushed back to Jerusalem to report to the apostles ‘and their companions’, only to discover it was not just to them that Jesus had appeared, but also to Simon! (24:33-34). And to cap it all, as the followers, including the women disciples who had first found the tomb empty and were now finding themselves justified against appalling male rudeness (24:11, 22-23), were excitedly comparing notes, suddenly to their general consternation, ‘Jesus himself stood among them and said to them, “Peace be with you”’! (24:36).

It has often been observed that if the followers of Jesus had wanted to create out of whole cloth a consistent account of the resurrection of their Master from the dead, they could surely have done a vastly better job than the bewildering array of confused and untidy stories which we have before us today as we read all the four gospels. In addition, Paul’s recital of the traditional list of appearances of the risen Christ of which he learned on his conversion and now repeated as commonly accepted to his Corinthian converts (1 Cor 15:3-7) – without any mention of the empty tomb, or of the women – contains additional intriguing details of appearances which none of the four gospels provides! It would be mistaken to regard all these fragments of memory, here in Luke and in the other passages, as so many tesserae in a mosaic, or pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, capable of being interlocked into a single coherent picture. The situation is much more like possessing a collection of particles whizzing around a nuclear truth: the still point, or central conviction, that Jesus had risen from the dead! The excitement at the unbelievable events, and the individual and group experiences, and the accumulating news, all proved too much for the wineskins of daily intercourse and coherent recollection in tranquillity.

Besides the many questions about the facts of what actually happened and to whom, there is also difficulty arising from conjecture: for instance, did Jesus appear to his mother? There is no mention of this happening, but many people, once the question has arisen, will simply reply that he must have. Ignatius of Loyola in his Spiritual Exercises, for one, lists the appearance of Jesus to his mother as the very first event of Jesus’s risen life on which retreatants should meditate. He acknowledges that this is not explicitly mentioned in the gospels, but he observes that ‘Scripture expects us to use our intelligence’.

The Significance of Easter

The liturgy of Easter contains a variety of themes and metaphors connected with the resurrection of Jesus designed to help believers and enrich our faith in what happened. In restoring his Son to life, for instance, the Father was doing incomparably more than just vindicating Jesus’s innocence in the face of the charges laid against him; he was conferring the glory of the risen life on his Son, the glory of which we had an anticipatory glimpse during the Transfiguration of Jesus (9:31). As Jesus was to argue to the Emmaus disciples, ‘Was it not necessary that the Messiah should suffer these things, and then enter into his glory?’ (24:26) This was the regular refrain of Jesus in his journey proceeding from Galilee to Jerusalem (9:22; 13:33; 18:31-34).

Another Easter theme, and the main one that figures now in the Easter Vigil service, whose gospel we are considering, is the acceptance of the risen Christ as a new light for humanity, emerging out of the darkness of death. It can be very impressive at the Vigil to see the candle lights springing up and spreading all through the darkened congregation, as people share the ‘light of Christ’ by receiving it from the paschal candle and passing it on to others; and to appreciate this as a living picture of the reality of our shared faith in the risen Christ, the faith which we are meant to continue to live afterwards as we draw continued enlightenment from Our Lord into the light of common day.

We can think of Jesus’s dying and death as a work of restoration, seeing the purpose of the incarnation as to repair the relationship of friendship between humanity and its creator God which humanity had destroyed through its sin of disobedience. Paul expressed this dramatically in 1 Cor 15:3-4 as ‘the good news . . . that Christ died for our sins.’ So much so, that ‘if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile and you are still in your sins’ (15:17). Now, however, through Christ ‘God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace through the blood of his cross’ (Col 1:20). Associated with this theme of reparation are various other expressions of recovery, including the offering of a sacrifice of reparation to God, unlocking the gates of heaven to erstwhile sinners, and identifying the risen Jesus as the great victor over sin and death. Connected with this also is the great theme of Exodus, the political and spiritual liberation of Israel from slavery in Egypt which is recalled in readings during the Vigil service, and has become for Jews and Christians alike the great symbol of God’s saving action in freeing his people from all types of subjugation.

A further significance of Easter which can arise today in the light of evolution, I suggest, is to view the incarnation as God having decided to unite himself with the evolving human species and to take on the evolutionary inevitability of death, breaking through in his human death and resurrection to a new phase of existence in union with God which the risen Christ shares with his fellow-humans.

‘I have risen and am still with you’

At the start of this series of articles I observed that keeping Lent can be seen as a time for a fresh start in our spiritual and religious lives; and the liturgical readings, especially the Sunday gospels taken from Luke’s Gospel which we have been looking at, can be seen as having been chosen to remind, inspire and encourage us to reflect on our lives, to examine our behaviour and also to think of what we can do for Christ in return for all that he has done for us. I also suggested that as we followed Jesus in his exodus to his prophetic fate in Jerusalem (9:31) we are offered an opportunity to take up our own cross – daily, Luke said (9:23) – and follow our Master in our pilgrimage. Now, as the Church’s observance of Lent closes with the celebration of the resurrection of Jesus at Easter, our thinking and our prayer can again reflect our belief as we now share Christ’s own human relief , satisfaction and gratitude at having achieved what his Father had set him out to do, and rejoice with him.

When I was a Jesuit novice in charge of the choir, well before the Second Vatican Council, I remember being particularly struck by the plainchant music for the Latin Introit verse for the Mass of Easter Sunday: Resurrexi, et adhuc tecum sum – ‘I have risen, and I am still with you.’ At first hearing, the Gregorian melody seemed remarkably plain and placid, almost dull, I thought. Then it dawned on me that the spiritual mood was not meant to be one of jubilation and delight and excitement, not at all Mozartian! It was a mood of peaceful self-awareness and quiet confidence. Musically, through the liturgy, Jesus was repeating his teaching to the women at the tomb, that he was certainly going to die, but equally certainly and confidently going to rise again from the dead. ‘Behold. I have risen and I am still with you.’

Three years ago in his homily at the Easter Vigil, Pope Benedict quoted these words, originally from the old Latin Psalm 138 (139):18, as being addressed prophetically by the risen Christ to his Father; but he went on to explain that they can also be understood as spoken by the risen Christ to each one of his followers. As the Pope explained, ‘“I arose and now I am still with you,’ he says to each of us. ‘My hand upholds you. Wherever you may fall, you will always fall into my hands. I am present even at the door of death. Where no one can accompany you further, and where you can bring nothing, even there I am waiting for you, and for you I will change darkness into light.”’

That is certainly ground for rejoicing, but not for surprise.

Jack Mahoney SJ is Emeritus Professor of Moral and Social Theology in the University of London and author of The Making of Moral Theology: A Study of the Roman Catholic Tradition, Oxford, 1987.

![]() Keeping Lent with Saint Luke

Keeping Lent with Saint Luke

![]() The Temptation of Jesus

The Temptation of Jesus

![]() The Transfiguration of Jesus

The Transfiguration of Jesus

![]() ‘Repent or Perish’

‘Repent or Perish’

![]() The prodigal son and his jealous brother

The prodigal son and his jealous brother

![]() The Woman Caught in Adultery

The Woman Caught in Adultery

![]() The Passion According to Saint Luke

The Passion According to Saint Luke