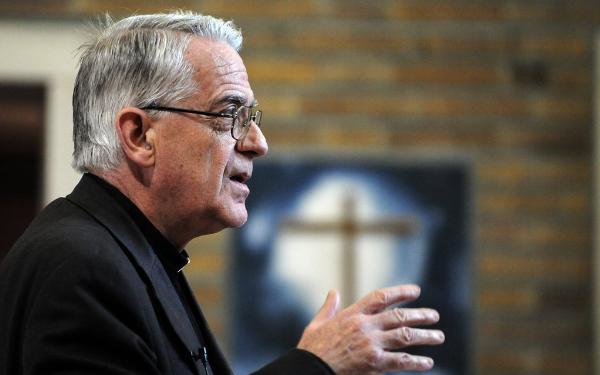

In the second part of his World Communications Day lecture, Fr Federico Lombardi SJ looks at the communicative styles of Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict, and speaks of the inevitability that the Church’s message will be a challenging one. How can those whose vocations lie in communicating this Gospel message avoid the dangers posed by the media?

We must not be of this world

In our service to the Church, we need to be constantly asking ourselves whether the limits and defects of our own communication skills in any given moment are making it more difficult for others to understand the Church’s message, so that they reject it, or whether the message itself is being rejected even though it has been understood – or precisely because it has been understood.

We are called to be witnesses to God’s love for humanity and for this world, but we cannot hide from the fact that the Gospel of Christ often becomes a sign of contradiction during the course of the vicissitudes of the world.

We cannot fool ourselves into thinking that a perfect communications strategy could ever make it possible for us to communicate every message the Church has to offer in a way that avoids contradiction and conflict. Truth be told, success in this sense would be a bad sign – at the very least, it would indicate ambiguity or compromise, rather than authentic communication.

I am convinced that in the present Pope and in his predecessor – and doubtless in others that came before them, as well, though I will speak of Benedict and John Paul II because I know them better – we have had and continue to have two eminent witnesses of the courage to speak the truth, to be oneself, and not to become enslaved to the desire for approval, which is one of the greatest idols of the modern world and of contemporary communications.

It is important to realise that many of the things the Church says – and that we should say if we would be faithful to Her – go against the grain. We need to hope that this is the case, not because we are outmoded or out of touch with the times in which we live, but because the Gospel of Christ is itself often against the grain.

To preach forgiveness in situations of hate and desperate conflict is against the grain. To preach a vision of human sexuality rooted in love and responsibility is against the grain.

To preach hope for a life beyond death to a world that is closed in on itself is against the grain, as is every concrete, everyday choice to live in faithfulness to Christ and His Church, a faithfulness founded on precisely that hope, which sees beyond death and yearns for eternal life.

Here we come to the very heart of communications in the Church, the heart of the Church’s mission of communication to and for the world. The ‘hard core’ that is strong enough to resist the trials and travails of history, is the credibility of the Gospel message, the authoritative character of the message that comes from authentic witness to the faith in the lives of the faithful. I am convinced that much of the respect that John Paul II earned from the world and from professional communicators, was at the end of the day a consequence not so much of his charisma as it was of his personal credibility. He was long criticised as a conservative, a retrograde, the ‘old Polish fellow’ unwise to the ways of the modern world and modern ideas, but at the end he was respected as a man of courage and integrity, firmly rooted in his faith and able to bear personal witness to it through all the different trials he faced during his long life.

Pope Benedict XVI has a very different personality, but no one can doubt his integrity and his intellectual and spiritual coherence. From these come his courage unabashedly to take and to maintain positions that are unpopular for those who have embraced the dominant culture. Think of his recent letter to the bishops; it is a most personal and admirably courageous communication. He expresses himself in the first person, repeating and defending the priorities and the criteria of action that he has set out for his pontificate, and leaves no room for doubt that his choices, as a generous search for reconciliation, have their deepest inspiration from the Gospel.

A few weeks ago, a journalist asked me to share my thoughts on good and evil in communications. In particular, he asked me to identify the principal faces of evil in our work and in the flow of communications.

It is easy to paint the big picture. The hard part is recognising the real, concrete, individual cases and situations, and then to put people on their guard, especially those most susceptible to the blandishments or tricks of evil.

There is the classical face of falsehood, more or less explicit, and often mixed with half-truths, motivated by interests of different kinds. It always aims to deceive.

There is the face of pride, of self-referencing self-centeredness that despises his fellows and refuses to listen to other positions, but seeks always and only the absolute affirmation of the superiority of his own position.

There is the face of oppression and injustice, that would deny his fellows’ freedom to gather information and give expression – the face of injustice that denies the voice of his fellows and so denies their basic human dignity and their rightful place in society.

There is the face of debauched sensuality that seeks to use and possess, and has respect neither for the body nor for the image of the other. This face expresses the materialistic hedonism that turns persons into brutes.

There is the face of escapism, which, seeking refuge in imaginary or virtual worlds, completely subverts the purpose of the new communications technologies, making them a source of isolation and slavery.

There is the face of division, that seeks to demolish dialogue, to undermine all efforts at mutual understanding among people of different creeds and cultures, and to set them against one another rather than to help them come together in genuine appreciation. This face becomes the face of conflict and war.

We need to learn to recognise these faces of evil for what they are, in order to make communications freely able to serve the good, that is, to further the construction of a culture of respect, of dialogue and friendship, and to place the immense potential of contemporary communications in the service of communion in the Church and of the unity of the whole human family.

Communication for communion: communicating with a view to unity.

This is the best expression I can find of my vocation as a communicator, of our vocation as communicators.

I have learned the need to discover ever anew the difficulties and the struggles of this vocation, and also the beauty and the greatness of it.

There is one precise moment that remains fixed in my memory, an unexpected illumination, in which, after many years, I understood the nature of the call to communicate.

There was a young people’s prayer gathering in the Paul VI Audience Hall, in which an aged John Paul II was taking part. CTV had set up ten or so different two-way satellite links so that young people in other European cities could take part in the broadcast.

Watching the giant screen in the Hall, the Pope saw the various other gatherings; he heard the young people’s greetings and greeted them in turn. We were all more than a little tense, owing to the complexity of the technical side of the operation – I remember because I was crammed in a tiny tech van with all my CTV colleagues and was sweating buckets.

At one point the Pope, with his characteristic spontaneity, said, ‘What a marvellous thing is this television! I can see and speak with my young people in Krakow as though they were right here. Blessed be television!’ I was stunned.

Think of all the terrible, awful things that television does, and now the Pope is calling it blessed! But he was right, of course. He sees further, for television really can create communion, it can allow the Pope and the whole Church, as it did that evening, to experience the joy of communion, and this is proof that television can be used for good, that it can truly be blessed! But this depends on us. We are the ones who must make television a source of blessing, and not leave it to become an instrument of corruption.

This, then, is my vocation – our vocation: we are called to make sure that the press, the radio and television are tools and paths toward blessedness. Now, I shall have to work more, all of us shall have to work even harder, so that every day it will be more and more true to say, and so that we might be able to say with greater and greater conviction: the internet is truly blessed!

Fr Federico Lombardi SJ is Director of the Vatican Press Office, Director of Vatican Radio and Director of the Vatican's television channel (CTV)

Taken from a lecture delivered at Allen Hall on 18 May 2009.

![]() Read Part One of Fr Lombardi's lecture

Read Part One of Fr Lombardi's lecture![]() Vatican News Services

Vatican News Services![]() Catholic Bishops' Conference of England and Wales

Catholic Bishops' Conference of England and Wales