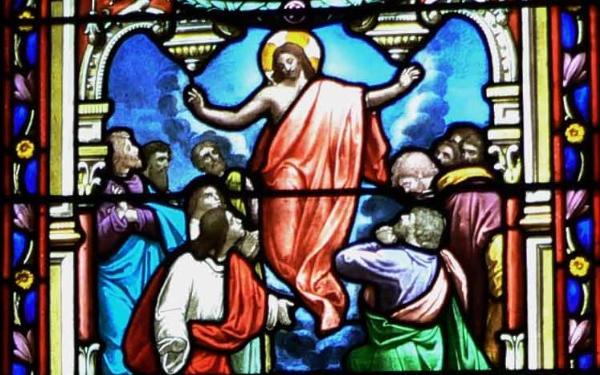

‘For Paul, Easter shapes and colours the very identity of God.’ In Easter week of the Pauline Year, Gerald O’Collins SJ explains what the apostle tells us about early faith in the resurrection. What did the resurrection mean for early Christian understanding of God, the Eucharist, and universal salvation – and what does it mean for us today?

As the earliest Christian writer, or at least the earliest Christian writer whose texts have come down to us, St Paul opens for us a window through which we can see what the very first Christians believed and practiced. Through his letters we can glimpse what they preached and professed, and how they worshipped.

In particular, Paul opens a window on their faith in the resurrection of the crucified Jesus. At the same time, the great apostle makes his own contribution by adding his firsthand witness to the risen Jesus and by interpreting in fresh ways the great truth of the resurrection. To illustrate this double function of Paul, let me take up four distinct themes about the resurrection: (1) the post-resurrection appearances of the risen Christ; (2) the identity of God as the God of resurrection; (3) the link between the Eucharist and the resurrection; and (4) the cosmic promise conveyed by Christ’s resurrection.

The post-resurrection appearances of the risen Christ

In a letter written around 54 AD, Paul quotes a concise formula about the resurrection that he had received when he joined the Christian community around 35 AD. He reminds the faithful in Corinth of this common testimony, which went back to the origins of the Christian movement: ‘I handed on to you as of prime importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he has been raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas [Peter], then to the Twelve’ (1 Corinthians 15: 3-5, emphasis added). Two verbs form the heart of this ancient formulation: ‘died’ and ‘has been raised’. The formula centres on Christ’s death and resurrection and presents these events as supported by historical and biblical evidence. Historically, the burial of Christ establishes the reality of his death: he was truly ‘dead and buried’. The appearances to Peter and then to the core group of Jesus’ original disciples (‘the Twelve’) establish the truth of the resurrection. Further, the death and resurrection took place ‘in accordance with the scriptures’. Those who had deeply pondered the inspired Scriptures they had inherited from Judaism (our Old Testament) should have been predisposed to accept the resurrection of the crucified Jesus. The formula does not cite any particular biblical texts, but we should think of passages that we know the first Christians treasured, such as one on the violent death of the servant of the Lord (Isaiah 52:13 – 53:12) and another on the glorious exaltation to God’s right hand of ‘my Lord’ (Psalm 110:1).

After recalling this key formula that he had received about Christ’s resurrection from the dead, Paul presses on in the next verses (1 Cor 15: 6-7) to list other appearances of the risen Christ that he knew of. Finally, he adds his own personal testimony: ‘last of all, he appeared also to me’ (1 Cor 15: 8). That meeting with the risen Jesus transformed the way Paul thought about God and about himself. It was the moment of grace that the apostle treasured for a lifetime. But what was it like?

In the Acts of the Apostles, Luke describes three times Paul’s meeting with Jesus on the road to Damascus, and has a fair amount to say about that encounter. But Paul himself remains discreet and even laconic. He has few words to say when it comes to reporting his life-transforming experience of the risen Jesus.

We have just cited the brief statement, ‘he [Christ] appeared also to me’. Earlier in the same letter, instead of phrasing matters in terms of the risen Christ ‘showing himself’ or ‘letting himself be seen’, Paul recalls the encounter which made him an apostle: ‘I have seen the Lord’ (1 Cor 9: 1). But what was it like to ‘see’ the risen Lord? In another letter the apostle remains equally laconic when he states that God ‘revealed’ his Son ‘to me’ (Galatians 1: 16). Once again, Paul’s version of his Damascus road experience does not press beyond a very general expression about the Son being ‘disclosed’ to him. We are left with the question: what was this revelation of the Son of God like?

In yet another letter, Paul lets us inside his experience of the risen Jesus when he writes: ‘The God who said “let light shine out of darkness” has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God on the face of Jesus Christ’ (2 Corinthians 4: 6). When we remember that, in the Scriptures, ‘glory’ often overlaps with ‘beauty’, we can say that in a new act of creation, which evokes the original creation of light, God let Paul glimpse the divine beauty on the face of Christ. The beautiful Christ took over Paul’s existence, became his great love, and transformed his existence forever. After that meeting with the beautiful, risen Lord, Paul was driven by one desire only: to spread everywhere the good news about the crucified and risen Jesus.

The identity of God as the God of resurrection

Secondly, through Paul’s letters we catch sight of a new way in which the Christian community described God: as the Father who had raised Jesus from the dead (Galatians 1:1; 1 Thessalonians 1:10). Being Jewish, the first Christians had inherited various ways of speaking about God: for instance, as the God of ‘Abraham, Isaac and Jacob’, as the God who had brought his people out of Egypt. In the aftermath of Jesus’ resurrection from the dead, they saw God through the lens of the first Easter and added a further divine ‘attribute’. They now spoke of God as the One who had raised and glorified the crucified Jesus.

Paul made his own contribution to this language by stating forcefully that belief in God stands or falls with the resurrection. When some of the Corinthian Christians began to have doubts about the resurrection of Jesus, Paul insisted: ‘if Christ has not been raised, then our proclamation has been in vain and your faith has been in vain. We are even found to be misrepresenting God’ (1 Cor 15:15). Obviously, it would be tragic for preachers to proclaim, and for their audience to believe, something that is simply untrue; but in religious matters an even greater error would be to ‘misrepresent’ God. To doubt or deny the resurrection means doubting or denying God. In other words, faith in the God who has raised the dead Jesus and will raise us with him, is no optional extra for Paul. Easter shapes and colours the very identity of God.

Some Christian groups in Britain have reacted to current publicity for atheism by paying for such counter-signs as: ‘There definitely is a God. So start investigating and enjoy eternal life’. Paul would want to be more specific: ‘There definitely is the God of resurrection. So start investigating and enjoy eternal life.’

The link between the Eucharist and the resurrection

Thirdly, after he was baptised and joined the Christian community, Paul found believers to be already celebrating the Eucharist on the Lord’s Day (Sunday) as their central act of worship. In his turn, he introduced Eucharistic practice when he founded local churches in Corinth and elsewhere. In the light of the Eucharist, he found it intolerable that factions split the Corinthian community. When seeking to heal these divisions, he reminded the faithful of what Jesus did at the Last Supper:

On the night he was handed over, the Lord Jesus took bread, and, after giving thanks, he broke it and said: ‘This is my body which is for you. Do this in memory of me.’ In the same way, he took the cup, after supper, and said: ‘This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Whenever you drink it, do this in memory of me.’ (1 Cor 11: 23-25).

After recalling the words and gestures that Jesus used at the Last Supper, Paul drew out the meaning of the Eucharist for the Christians at Corinth: ‘as often as you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the death of the [risen] Lord until he comes’ (1 Cor 11: 26). In this way, Paul summed up the meaning and message of the Eucharist as preaching the death of Christ – now invisibly but really present in his risen glory – in the hope of his future coming when human history ends. There is a straight line from what Paul wrote to the Eucharistic acclamation: ‘When we eat this bread and drink this cup, we proclaim your death, Lord Jesus, until you come in glory.’

Jesus instituted the Eucharist to express sacramentally what his death and resurrection would bring: an intimate fellowship among his followers, through a new covenantal relationship with God, which would endure until the final kingdom came. When tackling divisions that plagued the Christian community at Corinth, Paul went to the heart of the matter. By celebrating the Eucharist, they were proclaiming among themselves and to the world the death and resurrection of Jesus their Lord as they waited for his future coming in glory. How then could they tolerate the divisions that were wounding their union in the body of Christ?

The cosmic promise conveyed by Christ’s resurrection

Fourthly, when we read Paul’s letters attentively, we can spot some development in his thinking about Christ’s resurrection and its impact. In his very first letter, Paul reflects on the resurrection within a framework that his fellow Christians shared with him. When witnessing to their hopes about the final coming of Christ in glory, they and Paul think simply of the men and women who make up the Christian community, both those who will already be dead and those who will still be alive at the coming of the Lord (1 Thess 4: 13-18). All the faithful will be equally blessed at the end, and will live forever with the risen Lord.

Ten years or so later, Paul’s own horizon of thought about the resurrection has expanded dramatically. He now understands the resurrection to be working itself out, through the power of the Holy Spirit, for the good of the whole created world. The new age of final freedom from decay and death has already begun, and is a foretaste of the future, transformed universe. Whether they are aware of this or not, all human beings and the entire cosmos are in fact living in expectation of the definitive, glorious transformation that will come (Romans 8: 18-25).

Such then are four areas in which Paul enlightens us about the Easter faith of the earliest Christians, and what that faith entailed for him personally. Beyond question, there is much more to be added about that Easter faith and Paul’s reflections on it, but it is worth exploring at least these four areas. They let us see where the apostle adds precious details about his meeting with the risen Lord and his own insights about what Christ’s resurrection means for the identity of God, the celebration of the Eucharist, and Christian hope for the whole of humanity and the created universe.

The weeks and months of a special year dedicated to St Paul are slipping by fast. We would do well at the one Easter which falls in the year of Paul to pause and reflect on how the great apostle has enriched our knowledge and appreciation of the glorious resurrection of Jesus and what it holds out to us.

Gerald O’Collins SJ is a research professor at St Mary’s University College, Twickenham. His latest book, Catholicism: A Very Short Introduction, is published by Oxford University Press.

Read more of Thinking Faith’s series on Saint Paul:

![]() Who Was Saint Paul? – Peter Edmonds SJ

Who Was Saint Paul? – Peter Edmonds SJ

![]() The Long Road to Damascus – Bishop John Arnold

The Long Road to Damascus – Bishop John Arnold

![]() Paul the Pastor – Jerome Murphy-O’Connor OP

Paul the Pastor – Jerome Murphy-O’Connor OP

![]() The Vision of Saint Paul – Nick King SJ

The Vision of Saint Paul – Nick King SJ

![]() Getting to know Saint Paul today – David Neuhaus SJ

Getting to know Saint Paul today – David Neuhaus SJ

![]() Paul, Trinity and Community – Michael Mullins

Paul, Trinity and Community – Michael Mullins

![]() Power in Paul – David Harold-Barry SJ

Power in Paul – David Harold-Barry SJ

![]() St Paul and Ecumenism – Bishop John Arnold

St Paul and Ecumenism – Bishop John Arnold

![]() The Letter of Paul to the Philippians – Peter Edmonds SJ

The Letter of Paul to the Philippians – Peter Edmonds SJ

![]() The Letter to the Colossians: Jesus and the Universe – Brian Purfield

The Letter to the Colossians: Jesus and the Universe – Brian Purfield