Ian Linden, author of a new book on Global Catholicism, looks at the history of the Catholic Church in the fifty years since Pope John XXIII’s announcement of the Second Vatican Council. To what extent can the Church be described as a ‘World Church’?

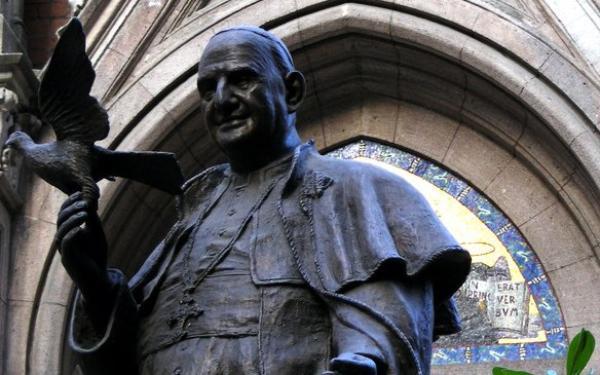

The first public announcement of the Second Vatican Council was made in the Basilica of St. Paul-outside-the-Walls fifty years ago, on Sunday 25 January 1959, the feast of the conversion of St Paul and the end of the – widely ignored in Rome – annual Octave for Christian Unity. Seventeen cardinals were present. Pope John XXIII’s sermon had been billed as a reflection on the ‘Church of Silence’, code-name for the persecuted Church in communist countries, and it was indeed silence that greeted his announcement: a frozen silence some thought, an ‘impressive and devout silence’[1] others later wrote.

Osservatore Romano printed the Pope’s strictures on Communism on the front page, relegating the announcement of the most important event in the life of the Catholic Church for almost a century to the centre pages. The official Vatican newspaper, the organ of the Curia, was behaving like the mirror image of the Communist newspaper, Pravda. The announcement shocked the future Pope Paul VI, Archbishop Giovanni Montini. ‘This holy old boy doesn’t seem to realise what a hornet’s nest he’s stirring up,’ he told a friend.

Well, the hornets are still flying. There is an insidious refrain heard in some parts of the Church that the Second Vatican Council undermined the firm edifice of Roman Catholicism and began the unravelling of Religious life in favour of secular pursuits. The counter-chant asserts that the Council saved a moribund Church, isolated and irrelevant in the modern world, and re-invigorated a declining Religious life by affirming its compassionate discipleship, striving for justice in the world. However, neither bears up to too rigorous an inspection. The Council did not represent a hiatus, a total break between the old Catholicism, before 1962, and the new, after 1965. New things were already happening before the Council, and old things continued afterwards. The Church was the crucible; the Council was the catalyst. It conducted Catholics into generous initiatives and engagements with the modern world, into deeper insights and changes in worship and spirituality. It brought together several slowly growing movements and gave them momentum and traction. Yet in several parts of the world it failed to stop incipient declines in vocations to the Religious life, in the number of priests, in Mass attendance and formal observance.

Looking Back

A fiftieth anniversary is a good time to reflect on what has happened to, and in, the Church in that half century and on what might happen in the next, none too easy a task when even the significance of the Council for Catholicism remains disputed. But few would argue against the simple proposition that during this time the Church has experienced what today we would call ‘globalisation’, to become what Karl Rahner called at the time of the Council a Welt-Kirche – a World Church.

It was through reflecting on this that I ended up with a glaring tautology, Global Catholicism, as the title of a book that had taken me over four years to write. My efforts were both an attempt to make sense of this half century of Church history, and a reflection on globalisation. The problem was that my research showed that this was a period when the ecclesiology of what might be meant by a World Church seemed to be disputed at every turn. In fact, what it meant became the core of a potentially profound fracture in the theology and practice of Catholic Christianity. On closer inspection, Global Catholicism was not so much a tautology as a description of a fault-line and of a site of struggle.

Did the phrase reflect the comforting thought that you would find the same Mass, the same Italianate statues, comparable Church architecture, vestments, and ways of doing things, dotted all around the world, so a Catholic when worshipping would be at home anywhere? Was it the proud thought that Catholicism had colonised the globe, planting identical structures, hierarchies and rituals here, there and everywhere, with 1.1 billion adherents making up its suffering or glorious membership? Or did it mean celebrating the extraordinary diversity and richness of the Catholic response to the Gospel message, created by the gift of the Spirit to different cultures, the creation of the universal Church from many different Churches?

Pluralism and Inculturation

The answer depends on how one views the most historically-sanctioned structures of the Church. A bishop is not, to quote the late Cardinal Lorscheider, ‘the local branch manager of the International Spiritual Bank Inc.’ That much could be agreed in theory at least. It might be inferred that the minimum requirement for a Church to merit the title ‘World Church’, rather being than a centralised international body in Lorscheider’s sense, would be that ideas and practices flow globally throughout its component structures and institutions. For it to be described in addition as pluralist in its internal structure and in its interaction with the modern world, a no doubt crucial requirement for a World Church, these flows would surely have to be without let or hindrance, encouraged and free. Moreover, the fundamental principle of Church unity would need to be balanced by a cherishing, a nurturing and a celebration of local diversity.

On this analysis, a fully global and pluralist Church is by nature collegiate, a community of communities, rather than a rigid hierarchical structure with its satellites controlled and ruled from a dominant centre. Or, in a definition given by the then Cardinal Ratzinger in July 1965: ‘the concept of collegiality, besides the office of unity which pertains to the Pope, signifies an element of variety and adaptability that basically belongs to the structures of the Church but may be activated in many ways…an ordered plurality’. It was a view that he appeared to set aside as head of the Church’s doctrinal congregation, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, when only ‘one way’ forward was countenanced.

The Nature of the Conflict

Global Catholicism as a contested terrain emerged most clearly in Latin America, the initial test bed for the ‘ordered plurality’ desired by the Council. I would argue that the quarter century battle over liberation theology was of course about perceptions and misconceptions with regard incorporating seemingly Marxist methodologies into pastoral practice and social analysis, but no less about the possibility and legitimacy of an inculturated theology, that is a non-Roman theology that spoke to the condition of Christians in their social and political particularity. This was but one dimension – perhaps the most important – of a wider conflict about the degree to which Catholicism could be expressed in anything other than an Hellenic thought-form and practice, an essentially European cultural form, promoted by Rome. This conflict manifested itself in such questions as whether to permit altars to ancestral spirits or Milingo-style healing, or Jon Sobrino’s Christology at the Crossroads.

Once it is admitted that the Catholic Church contains a variety of compelling positions as regards the nature of pluralism and inculturation or, as Pope Benedict wants to call it, ‘inter-culturation’, ‘Global Catholicism’ becomes somewhat less of a tautology, more a contested goal.

The Cold War

The struggle surrounding liberation theology cannot be understood outside the context of the Cold War. The history of the last fifty years, dominated by the Cold War, strongly suggests that the Catholic Church, while having an obvious presence and influence all round the world, has been some way from being a genuinely World Church in the sense described. This is trivially true when considering the distribution of high offices and influence in Rome, but more profoundly true in the priority given to certain preoccupations, problems, and political options, with those of European and North American cultures dominating concerns for much of the time. The concern about varied aspects of human sexuality would be the most striking example. The geographical distribution of Catholic Christians and their major preoccupations by the end of the millennium, were, and are, poorly and disproportionately reflected in the priorities – spiritual and intellectual – of the Vatican, and in the allocation of leadership positions in Rome. The notable and important exceptions would be the concern for peace and human rights during this period, both global themes but particularly pertinent to the life of Catholics in the developing world.

A Church growing strongly in the ‘Global South’ and diminishing rapidly in the North has remained stubbornly Eurocentric in its central leadership and primary concerns. The way that the Cold War split this Eurocentric Church, in some ways no less than the rest of the world, was particularly revealing. With the benefit of hindsight, what is astonishing was the almost total lack of understanding between the persecuted Church of the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China and North Korea and the Church of the martyrs in Latin America, the Philippines and South Africa. Here were Catholics bearing witness to and dying for their faith in two different political contexts: the former countries faced communist governments set on wiping out religion, and the latter suffered under military dictatorships and oligarchies set on sustaining religion in their own image. Never did a real meeting of minds take place. Instead, meetings took place in a sea of unresolved misunderstanding and political preconceptions. Did the central government of the Church in Rome bring the two sides together to discuss the divisions that every Superior General of a Religious Order knew existed and simmered away in General Chapters? Not that I am aware of. Synods of bishops were fraught when it came to justice issues. Pope John Paul II’s depth of understanding of, and empathy with, the Eastern European predicament was matched by preconceptions about Latin America and liberation theology that remained unresolved despite his obvious empathy with the poor of that continent. He was the missing mediator and no other appeared.

Things have moved on. But the quest for a genuinely Global Catholicism will perhaps at one level always remain a work in progress for a missionary Church. The end of the Cold War may have been the precondition for an ‘ordered plurality’, for finding the right relationships to nurture cultural diversity, and ad extra,dialogue with other religions and secularism. Pope Benedict is obviously concerned about this quest lapsing into a dangerous form of relativism[2]; he has said as much and is acting accordingly. But he is no less European than his predecessor. The next step may be a Pope who brings, in his own person, the Global South to the heart of Rome, rather than it just visiting in ad limina visits. I wonder if Rahner would be pleasantly surprised at what his vision of a Welt-Kirche had become today? Or perhaps a little disappointed.

Ian Linden is a Professorial Research Associate at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London, and Director of the Faiths Act project of the Tony Blair Faith Foundation. He is the author of Global Catholicism: Diversity and Change since Vatican II, published by Hurst on 19 January 2009.

[1] Hebblethwaite, P., John XXIII: Pope of the Council, Chapman: 1984, p. 323

[2] Allen J., Benedict XVI, Continuum: 2001, pp. 165-167

![]() Tony Blair Faith Foundation

Tony Blair Faith Foundation![]() Global Catholicism

Global Catholicism

![]() Read Thinking Faith's review of Global Catholicism

Read Thinking Faith's review of Global Catholicism