In December 2008, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith released a new document about the issues surrounding IVF and embryo experimentation. Dr David Jones offers a guide to the principles appealed to and the issues addressed in Dignitas Personae, and asks how this timely teaching applies to recent debates in the UK regarding hybrid embryos and stem cell research.

The Instruction Dignitas Personae on Certain Bioethical Questions was released by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith in December 2008. This new Vatican document about in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and embryo experimentation is an update of a document written twenty years ago, Donum Vitae (1987), and seeks to address the questions raised by recent developments in biomedical research.

Why now?

In the last twenty years there have been many developments in fertility treatment and in the use of human embryos and so there was an obvious need to update Church teaching. Some of these new questions were examined in the 1995 encyclical of Pope John Paul II, Evangelium Vitae, but there have been still other developments since then. In recent years, there have also been political and legal changes in parallel with scientific developments. The United Kingdom has just passed a new law on fertility treatment and embryo experimentation: the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008. The new administration in the United States, elected in 2008, is expected to pursue a very different policy on embryonic stem cell research: George Bush had vetoed federal funding for embryo experimentation but Barack Obama has stated that he will approve it. The Vatican has been watching these developments closely and is aware of specific challenges faced by different countries. The document is written with an international audience in mind.

How authoritative is it?

This is a document from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF). The CDF exists to support the Pope in providing clear teaching on Church doctrine. The Pope has explicitly approved the document and therefore it shares his ordinary teaching authority. This kind of instruction does not have quite the same status as a Papal encyclical or a Church council, but it carries great weight. It is possible to criticise the way in which the CDF might express itself, or the wisdom of speaking on a particular issue at a particular time, but very strong reason is needed to dissent from the teaching itself. Dignitas Personae gives the most up-to-date official Catholic view on bioethical questions.

What topics does it cover?

The subheadings in the second and third parts of the document provide a useful summary of the issues addressed in Dignitas Personae:

Second Part:

- New Problems Concerning Procreation

- Techniques for assisting fertility

- In vitro fertilisation and the deliberate destruction of embryos

- Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) [a form of IVF]

- Freezing embryos

- The freezing of oocytes [women’s eggs]

- The reduction of embryos [selective abortion]

- Preimplantation diagnosis [screening embryos]

- New forms of interception and contragestion [e.g. the morning after pill]

Third Part:

- New Treatments which Involve the Manipulation of the Embryo or the Human Genetic Patrimony

- Gene therapy

- Human cloning

- The therapeutic use of stem cells [embryonic and adult stem cells]

- Attempts at hybridization [trying to creating human-animal hybrid embryos]

- The use of human ‘biological material’ of illicit origin [e.g. cells from aborted foetuses]

Are there issues that are not covered?

The document has made a valiant attempt to cover the main new issues in fertility treatment and the use of human embryos. However, it cannot cover everything and some prominent issues that arose in the UK debate about the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008 were not included, probably because they were raised at a very late stage. The United Kingdom is allowing the creation of clone and hybrid embryos for scientific experimentation without the consent of the adult who gave the tissue. This raises not only the issues of embryo destruction and cloning but also the issue of procreation without consent. The use of someone’s gametes or cells to create an embryo without consent contradicts the nature of parenthood.

No doubt there are also other issues that are not covered – this is an area that is rapidly changing so no document can be expected to cover everything. One thing which can and must be said is that if some particular issue is not covered in the document, it cannot be deduced from this that the process or concept in question is acceptable. It might be acceptable or it might be wrong. The principles set out in the document need to be considered and applied to other situations which are not directly addressed.

What is the significance of the title?

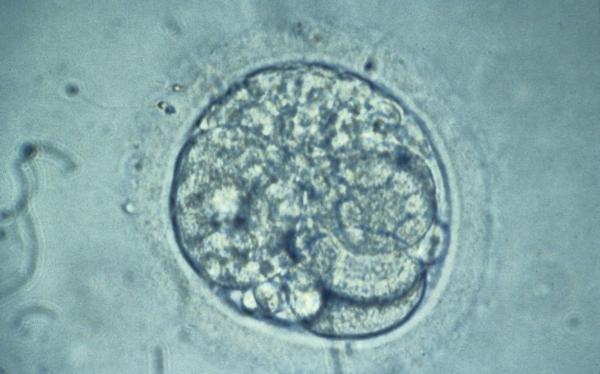

The title Dignitas Personae echoes that of the Second Vatican Council document on religious liberty, Dignitatis Humanae. In something of a contrast to Donum Vitae (whose title was a deliberate echo of Humanae Vitae), the focus of this new instruction is less on the transmission of life and more on the dignity possessed by the human embryo. The word persona in the title, rather than vita, emphasises that the human embryo is a personal reality sharing in human dignity. It is not only a means by which life is transmitted. ‘The human embryo has, therefore, from the very beginning, the dignity proper to a person’ (5)

What principles does the document appeal to?

Dignitas Personae reaffirms the two key principles of Donum Vitae and of Evangelium Vitae and applies these to new questions. The two fundamental ethical principles affirmed by the document are:

· The human being is to be respected and treated as a person from the moment of conception; and therefore from the same moment his or her rights as a person must be recognised, among which in the first place is the inviolable right of every innocent being to life. (4)

· The origin of human life has its authentic context in marriage and in the family, where it is generated through an act which expresses the reciprocal love between a man and a woman. Procreation which is truly responsible vis-à-vis the child to be born must be the fruit of marriage. (6)

A third principle relates to the proper distribution of the benefits of research:

· [The Church] hopes moreover that the results of such research may also be made available in areas of the world that are poor and afflicted by disease, so that those who are most in need will receive humanitarian assistance. (3)

These principles help to distinguish between authentic medical science at the service of the human person and the common good, and research or treatment that fails to respect the dignity of the human person and may even involve the deliberate destruction of human lives.

Is this a development of church teaching on the embryo?

The first key principle of the document, on the moral inviolability of embryo, is in fact a quotation from Donum Vitae. The document does not say that the human embryo is a person but that it must be ‘respected and treated as a person’ as it has ‘the dignity proper to a person’. The human embryo has ‘full anthropological and ethical status’(5). The implication is clear: human embryos must not be deliberately destroyed or abandoned, nor should they be conceived irresponsibly in circumstances where they will not be given a chance of life. The document does not define, as a matter of faith, that the spiritual soul is given at conception; it repeats the teaching of Donum Vitae that ‘the presence of the spiritual soul cannot be observed experimentally’. (5)

Recent Vatican documents are moving closer and closer to a line without actually touching it. Theologians are more and more convinced that the evidence from science and the arguments of philosophy support the view that the embryo is a human person with a spiritual soul from the moment of fertilisation. Nevertheless, they are aware that there are different views on when, precisely, the soul is given and so are cautious about making this a matter of faith. What is key is not the question of the soul, but the real protection for embryonic human beings. In this case the primary concern of the Church is moral and practical rather than metaphysical.

How does the Church regard scientific research?

In this document the Church offers a positive picture of ethical scientific research. ‘The Magisterium also seeks to offer a word of support and encouragement for the perspective on culture which considers science an invaluable service to the integral good of life and dignity of every human being. The Church views scientific research with hope and desires that many Christians will dedicate themselves to the progress of biomedicine and will bear witness to their faith in this field.’(3) The document strongly encourages scientific endeavour that is both ethical and effective in areas such as research ‘involving the use of adult stem cells’ (32).

Why are these issues so prominent in the United Kingdom?

It should be remembered that the first child born after in vitro fertilisation (in 1978) was conceived in the United Kingdom, as was the first child born after preimplantation diagnosis (in 1989), as was the first cloned sheep (in 1997). For better or worse, this is an area in which the United Kingdom has been at the forefront of developments.

Since 1990, in vitro fertilisation and embryo experimentation have been regulated by a statutory body: The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). This is sometimes said to be ‘strict regulation’ but in fact in nearly twenty years the HFEA has never refused a license for embryo experimentation. The HFEA pays lip service to the ‘special status’ of the human embryo but has never turned down any application to use human embryos. The membership of the Authority does not reflect a full range of opinion on the embryo: it has no members who hold the embryo to be inviolable.

How does Dignitas Personae apply in the current UK context?

The instruction is addressed to ‘all who seek the truth’ and has a global audience, but it has particular application in the United Kingdom and some passages seem addressed especially to the situation here, for example the discussion on animal-human hybrid embryos (33).

In the current UK context, Dignitas Personae is a welcome reaffirmation of the fundamental principle that embryonic human life is to be respected and protected with the utmost care. Since the first child conceived by in vitro fertilisation there have been tens of thousands of children born by this method, but there have been hundreds of thousands of embryos deliberately destroyed or discarded. At any one time there will be thousands of human embryos frozen in various fertility clinics within the United Kingdom.

Dignitas Personae prompts us to remember these frozen lives, many of whom have been abandoned by their parents to be discarded or handed over for experimentation. Of particular relevance for the UK is the plea of Pope John Paul II, quoted in Dignitas Personae, that ‘the production of human embryos be halted, taking into account that there seems to be no morally licit solution regarding the human destiny of thousands and thousands of ‘frozen’ embryos which are and remain the subjects of essential rights’.(19)

Dignitas Personae is also helpful in a UK context for its teaching on human cloningand on hybrid embryos. These passages give magisterial force and an explicit rationale to the case that the Catholic Church, among others, has been making in the United Kingdom. Though cloned and hybrid embryos have been approved by Parliament, it is important to restate the Church’s objection to them. In this area many non-Catholics feel a repugnance that they find hard to articulate, and the teaching of the Church is heard sympathetically by many people.

Another specific teaching that is welcome is the affirmation that parents may use vaccines produced from aborted foetuses, if this is the only way to protect their children.(35) However the document also urges against too easy a compromise on these kinds of ‘cooperation’ issues.

Also significant, from a United Kingdom perspective, is the promotion of ethical science and especially adult stem cell research. During recent debates in Parliament, some politicians denigrated adult stem cells as unpromising. However, only a week after the Bill was given royal assent, there was a report from Spain of a whole organ grown from stem cells taken from a woman’s bone marrow. There is clearly a long way to go in adult stem cell research but enough has been achieved so far to show that the promise is real and that this research should be celebrated, promoted and encouraged, instead of embryonic stem cell research.

Are there parts of the document that are directed at other countries?

Some issues in the document are less relevant to the United Kingdom, as would be expected from a document addressed to a global audience. More than once the document cautions against, or rules out, various compromise solutions, for example the use of embryonic stem cells produced ‘independently’ by someone else. Recently, University College, Cork, decided to begin doing embryonic stem cell research using cell lines that had been produced in other countries. No embryos would be destroyed in Ireland, but the embryos would have been destroyed for their cells in another country. The justification here is that it can sometimes be legitimate to use knowledge or material that comes from injustice, if you have had no part to play in the injustice. However, while embryos are being destroyed every day in experimentation it is scandalous to work on cells from an embryo that someone else has destroyed – this is just getting someone else to do your dirty work.

Another example of a compromise proposal is the freezing of oocytes (women’s eggs). This allows an alternative form of IVF which does not involve freezing embryos and so does not result in the deaths of so many embryos. The intention behind freezing oocytes, which is practised in Italy and elsewhere, may be to help protect embryos, but it still involves the practice of IVF, which has other ethical problems. IVF separates the act of marital union from the production of offspring. It involves an element of manufacture and has been consistently criticised in Church documents. Therefore, while freezing oocytes may be less objectionable than freezing embryos, it is still problematic. There is no such thing as Catholic IVF.

Another compromise proposal, one that has been accepted in the United States, is to allow people to ‘adopt’ frozen embryos that have been abandoned by their biological parents. This idea has some support among Catholic theologians and pro-lifers, but again it seems to imagine a form of Catholic IVF using someone else’s embryo. Dignitas Personae is the first official Church document to consider the ‘embryo adoption’ argument and it states the argument is problematic (19). There is no clearly acceptable ethical solution to the problem of frozen embryos abandoned by their parents. The real solution is to make sure that these unwanted embryos are not created in the first place.

In the United Kingdom, these compromise issues are less relevant as the situation is such that the compromises are not even suggested. In this country the deliberate destruction of human embryos is both licensed by the state and paid for by the tax-payer. Alas, in relation to the human embryo, the United Kingdom is near the bottom of the league table for ethical standards. Dignitas Personae, then, may be welcomed as a timely and challenging comment on recently legalised UK practices and a call to rethink the implications of scientific advancement on the dignity of the person.

Professor David Albert Jones is the Director of the Centre for Bioethics & Emerging Technologies at St Mary’s University College, Twickenham, and author of The Soul of the Embryo: An enquiry into the status of the human embryo in the Christian tradition.

![]() Dignitas Personae

Dignitas Personae![]() Centre for Bioethics and Emerging Technologies at St Mary?s University College, Twickenham

Centre for Bioethics and Emerging Technologies at St Mary?s University College, Twickenham![]() The Soul of the Embryo at Continuum Books

The Soul of the Embryo at Continuum Books![]() 'An Ethical Look at Human-Animal Embryos' by David Albert Jones

'An Ethical Look at Human-Animal Embryos' by David Albert Jones