Many commentators on the crisis that has rocked banks and stock markets all over the world would tell us that the problem is simply greed. But a brief look at the remarkable insights into economics of the Canadian Jesuit, Bernard Lonergan, would suggest a rather different diagnosis, as well as a new way out of our recurring economic injustices, argues Peter Corbishley.

“Greed and fear on the way up and greed and fear on the way down” was how the editor of a national newspaper, speaking recently on BBC TV, characterised the current economic crisis. His version of key economic drivers, as well as his belief that boom and slump are the inevitable counterpart of these drivers, presents a bleak scenario of the human condition. Runs on banks, the ‘credit crunch’, job losses are an inevitable part of what it is to be human. Maybe all moralists, secular and religious, concur on greed as the root of the present malaise. Bernard Lonergan would beg to differ. In 1980, while describing how recession turns to depression, into a crash, and even stagnation, he wrote:

In equity it (the basic expansion) should be directed to raising the standard of living of the whole society. The reason why it does not is not the simple-minded moralist’s reason: greed, but the prime cause is ignorance. … When people do not understand what is happening and why, they cannot be expected to act intelligently. When intelligence is a blank, the first law of nature takes over: self-preservation. It is not primarily greed but frantic efforts at self-preservation that turns recession into depression, and depression into crash.[i]So, in our ignorance, we are now heading for a recession, and maybe worse: panicking by queuing up outside Northern Rock, promoting non-competitive mergers or spending billions of public money on bailing out the banking system. But what is that we are ignorant of?[ii]

Social teaching

Stephen Martin has recently shown how in comparison with Lonergan the diverse insights of Catholic social teaching are rather like sheep without a shepherd. [iii] The insights are there, but taken on board differently by different people and so the real analysis easily shifts from the body of Church teaching to other, and often non-economic, forms of analysis.[iv] For Lonergan even the Church’s most economically prescriptive social teaching, say on the living wage, is difficult to apply judiciously in a modern economy. So the strong presumption in Catholic Social Teaching in favour of private property might well have been quoted in support of the recent drive in the USA and the UK to extend home ownership as widely as possible, but that drive has led us into the present housing bubble and ensuing crisis in the money markets. Similarly, more or less all of us are against ‘unbridled profit’, as even the phrase suggests. But what level of profit is allowable? And is the same level of profit justifiable at all stages and in all sectors of a modern economy? In this area at least, to be effectual, moral principles need the grounding of technical specifications. [v]

Autobiographical contexts

Lonergan’s interest in the workings of the economy lay in his own experience of the depression in the Canada of the 1930’s and the rise of Hitler in Europe. He was, for example, studying for his BA finals at London University in 1929-1930, and had to hurry home from Rome back to Canada before World War II. He had practical understanding of the way in which the strictures of the Social Credit Movement were a recipe for economic disaster for those business people who tried to apply them. He saw how economic upheavals could have drastic political consequences. Further his work on economics is an expression of his intellectual concern, developed while still at Heythrop College, for how we are to participate in a redemptive, and so progressive, human history – a topic we return to below. Later, with the development of his general account of world process, known as emergent probability, he understands levels of technology and standards of living as emergent within economies. The question he faced up to was how standards of living could be distributed equitably across everyone living within a modern economy.[vi]

A religious perspective

Yet it needs to be emphasised that during this period he also became a Jesuit and a priest. So he undertakes his dialogue with economists such as Keynes, Klecki, Kregel, Robinson, Saffra, Scuhmpeter and Walras from within a religious horizon. He has in mind, as he used to say in asides during his lectures, the needs of the ‘widow and the orphan’. His dialogue, too, is increasingly based on his personal encounter with the mind of Aquinas and so reflects not the manuals on Aquinas but a shared desire to bring new things out of the old. Lonergan’s first step, then, is not to appropriate the Church’s social teaching and then step into the direct application of that teaching. Rather he engages in a three step process. He takes a first step backwards into the vetera. Then, working with the dynamism given by the ‘old’, he takes a second step out of the immediate arena of practical engagement and enters into a somewhat lonely dialogue with modern economists. He was unable personally to take the third and forward step into practical application, but the need for that step is increasingly evident. George Soros[vii] for example, calls for a new paradigm for economics based on a different epistemology to the one he sees as prevailing. It is to the merit of Lonergan that his dialogue with Aquinas provides a grounding for such an epistemology, and that his dialogue with economists provides them with a paradigm that enlarges the world in which they, and so all of us, might one day live, while remaining true to the Gospel.

Insight into a sustained path for economic growth

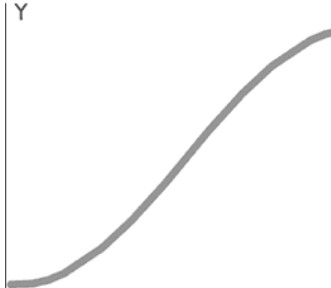

Lonergan’s fundamental insight is to identify an S-shaped cycle for the economic cycle. With proper management of the economy we can smooth out the cycle of ‘boom and bust’ into an S-shaped wave. [viii] He comes to this insight through recognising that any economy, from earliest times onwards, operates with two separate circuits - one related to consumption and the other to production. A modern economy, he argues, does not run through a single circuit from production to consumption, moving up and down like a roller coaster between boom and slump, but through two. The first Lonergan calls the basic circuit, the second the surplus circuit. The S-shaped curve is Lonergan’s account of how we could link these two circuits together to smooth out the ride into a single upward movement.

Basic and surplus circuits

The initial distinction between basic and surplus circuits can be noted from the fact that from early on in human social development we give time to creating technologies. We take resources from the basic task of finding and consuming a standard of living and devote this surplus to developing technologies. In the basic circuit of the economy we deliver a standard of living to each other, but in the surplus circuit of an economy we invest in developing new technologies which expand the means of production and provide the basis for a higher standard of living.[ix] The economic requirement for literacy and education in modern economies requires that young people be taken out of direct production and placed within the surplus circuit so that at a future date the society as a whole reaps the benefits of the higher standard of living that comes from higher educational standards. An individual, too, can take time out from earning a living to undergo training or receive education before returning to the work place to earn a higher standard of living, as is still generally the case for UK graduates from university.[x]

The surplus expansion

The expansion of the basic circuit provides a higher standard of living. The expansion of the surplus circuit expands capital formation to underpin higher standards of living in the basic circuit. Surplus expansion comes about through investment in technological, or as we have just indicated, in ‘human’, capital. As investment in capital develops, surplus expansion becomes increasingly complex. We will illustrate a simple one-to-one investment in making a knife, and then something of the complexity of the multi-levelled structure of capital development using the example of the clothing sector in an economy where innovatory investment is driven firstly by industrial and then by scientific revolutions.

The knife culture

In ‘pre-historic’ leather manufacturing[xi] a cutter uses a single knife to cut up an animal skin to produce a leather ‘coat’. One animal leads to one ‘coat’, but the one knife can be used time and time again. Time, it is true, has to be taken out from hunting animals in order to make the knife in the first place, but once made, the knife increases efficiency. A technological innovation becomes part of an economy. Making the knife brings in a line of production – that of making knives – that is surplus to the basic stage of production in which we make and sell ‘coats’, for example. The knife improves the standard of living as the ‘coat’ is now no longer just something ‘thrown together’ across the shoulders. Equally importantly, there develops a secondary level of production which makes the machines that make the knives. In addition the machines that make the knives for cutting leather can also be used for making knives that do things other than cut leather or make clothes.

The machine culture

As we have just indicated, machines are used to make tools, and, in turn, machine tools are used to make machines. There is not only a basic circuit of production and consumption, but there are one or more secondary or surplus lines of production producing the machines that produce the machines. Staying with our example of the clothing industry, plantations produce cotton like hunting foxes produces the material for fur coats. But, as the industry develops, cotton gins clean cotton, spindles make that cotton into cotton thread, looms weave the thread into cloth, and sewing machines make the cloth into cotton dresses.[xii] One cotton plant is still made into one cotton dress, but time and money has been taken out from making cotton dresses to make the machines that make the cotton gins, the sewing machines, the looms and so on. The introduction of different power sources – water, steam, electricity – further increases the possibilities for ranges of available machinery. So we can have a great number of levels of production, not all focussed on the clothing industry, which are in a hierarchy of removes from the basic stage of making a dress or a suit purchased as part of a standard of living. [xiii] Investment in the application of new power sources in new types of factory, or in investment utilising new scientific knowledge leads to further expansion of the surplus circuit.

Raising capital for the expansion of the surplus circuit

The complexity of modern capital investment in the surplus circuit of production can be glimpsed from Andrew Marr’s recent BBC series on ‘Britain from Above’. More importantly, from an economic point of view, is the sheer scale of the capital investment and the time required to invest in inventions that expand existing levels of surplus production in such a modern complex society. The amount of money is one thing, but it may well be the case that years go by before new goods are sold into either the surplus or basic circuits. If the benefits of new inventions are to be shared across the society, somebody has to take the risk of investing in the latest wave of innovation, in a new level of surplus expansion. Historically, risk-taking individuals have invested in what we are calling a surplus expansion. Our understanding of the risks of such entrepreneurship gives us our understanding of profit.

The role of profit

Raising money for the surplus expansion is relatively unproblematic. “The fact, of course, is that no difficulty is experienced in financing the surplus expansion. It is the first step towards increasing the standard of living of the whole society, and there seems to be little evidence that entrepreneurs, financiers, engineers, workers, are commonly hesitant about taking that step.”[xiv] A major reason is profit. Shortly we again quote Lonergan at some length on profit, but, given his reference to equity in the first quotation above, we should note that he recognises the value of the anti-egalitarian shift involved in risk-taking investment in the surplus expansion. In that sense, he is not anti-capitalist. Risk-taking investment in a surplus expansion realises the possibilities open to us in an emergent world order. Nor is he anti-socialist in that he stresses the importance of ‘to us all’, namely the ‘egalitarian shift’ that comes from the full expansion of the basic circuit within a given economic cycle. The moral norms for the surplus expansion can be said to be ‘thrift and enterprise’, those for the basic expansion might well be ‘benevolence and enterprise’. Neither set can be applied without regard to our technical understanding of where we are in the economic cycle.

Signalling the transition into the basic expansion

Lonergan, therefore, distinguishes between a surplus circuit and a basic circuit within the economic cycle. His economic model moves from investment in expansion of a surplus circuit to investment in expansion of a basic circuit. Investment in a surplus circuit increases the efficiency of production. Investment in a basic circuit creates rising wages and falling prices. Our critical mistake is to apply the rate of profit appropriate to risk-taking investment in the surplus circuit to investment in the expansion of the basic circuit. Profit moves from being a motive to being a criterion of economic activity. Profit-making as a motive for risk-taking investment in new technology is one thing, entrepreneurial rates of return as a criterion for low-risk investment is another. Moreover, if in fact we are investing in generalising the benefits of new technology to new consumers in the basic circuit, but we continue to expect the level of profit that motivates a surplus expansion, then sooner or later we will lead ourselves into a slump. The slump begins, that is, when the providers of low-risk investment in the expansion of the basic circuit find that entrepreneurial level profits are not materialising and they use this fact as the criterion for contracting their operations. To maximise the standard of living realisable within the possibilities of a given technology, we have to have economic reasons for changing the expectations about profit that currently surround investment in the basic expansion. So, for Lonergan the economic reasons are that firstly ‘profit’ is a social dividend produced by the economic expansion of the surplus circuit, and that, secondly, to avoid the bust that follows boom we have to learn how to manage the distribution of that dividend across the longer cycle of the economy. The requirements for a ‘normal profit’ remains, but any excess over that is a social dividend. “It is not money to be spent. It is not money to be saved. It is money to be invested …..”[xv]

The social dividend

In accounting terms, profit is simply the excess of what has been received over what has been paid out. When profits are ‘excessive’ this definition of profit easily leads to demands for higher wages, or for the lowering of prices. Lonergan, however, is not focusing on the accounting understanding of profit. Instead he is pointing to a social dividend that, at certain phases of the economic cycle, is available to invest in raising the standard of living of the whole population. The social dividend is founded on ‘pure surplus income’, namely the income over and above the income required for current consumption and the current replacement of what is required to produce that level of consumption. All organisations require the consumption and replacement income that keeps Mr Micawber happy and provides the ‘constant normal profit’ familiar to so-called ‘not-for-profit’, co-operatives or third sector organisations within our own society. In aggregate ‘pure surplus income’ is what is left over when normal profits have been made. Lonergan identifies pure surplus income with ‘net aggregate savings’, namely the money available to the whole economy that does not need to be spent to maintain the standard of living of that economy.

Identifying pure surplus income – in Lonergan’s own words

However, the phenomena here referred to by the term ‘pure surplus income’ are not, as is the term, a creation of our own. The phenomena are well known. Entrepreneurs are quite well aware that there are times of prosperity in which even a fool can make a profit and other mysterious times in which the brilliant and the prudent may be driven to the wall. Entrepreneurs are quite aware of the ideal of the successful man, a man whose success is measured not by a high emergent standard of living nor by the up-to-date efficiency of some industrial or commercial unit but by increasing industrial, financial, and social power and prestige. In the old days when the entrepreneur was also owner and manager, pure surplus income roughly coincided with what was termed profit. Today, with increasing specialisation of function, pure surplus income is distributed in a variety of ways : it enters into [the] very high salaries of general mangers and top-flight executives, into the combined fees of directors when together these reach a high figure, into the undistributed profits of industry, into the secret reserves of banks, into the accumulated royalties, rents, interest, receipts, fees, or dividends of anyone who receives a higher income than he intends to spend at the basic final market.[xvi]There are echoes here of the contemporary moral condemnation of windfall profits, excessive city bonuses, high salaries, and the life styles of the ‘rich and famous’. However, Lonergan moves on from decrying individual ‘greedy bankers’ on Wall Street or in the City to an account of how we can establish an economic order that is both efficient and moral.

The “baseball” diagram

We have briefly introduced Lonergan’s key distinction between surplus and basic circuits which allows him to distinguish between two different types of growth or expansion. However we have not described the ‘baseball diagram’ which Lonergan uses to express mathematically the financial flows across production, consumption and redistibutional circuits as supply, demand and redistributional functions.[xvii] The redistributional function works through banks, investment companies, colonial powers, international companies, larger firms and wealthier individuals who ‘pitch’ quantities of money into the circuits. Their actions accelerate and decelerate the movement of finance between the surplus and basic circuits, within and across economies, often further impoverishing the weaker. In the context of the contemporary crisis, the resale of houses is redistributive, whereas financial operations are partly redistributive and partly payments for services that are part of the basic circuit. So in terms of the current debate in the USA there is not only a Main Street and a Wall Street, but an ‘E’ Street [xviii] that invests in the long term surplus expansion. Current liquidity problems in the redistributional circuit may spill over into a depression in the High Street - to revert to a UK phrase – and to increasing unemployment leading to a real contraction in the basic circuit. What Lonergan enables us to note is that the loss of liquidity may also negatively affect entrepreneurial investments in, say, the technologies of renewable energy, which in the UK are not currently regarded as ‘commercially’ viable, and this would lead to a failure to realise the possibilities actually available to us in the face of climate change.

Research into the categories of the analysis

Lonergan has provided just a beginning. Work needs to continue on understanding his theoretical work. But for that to become practical we also need to be able to ‘read off’ which parts of an economy are in the surplus or basic circuits. Our present economic statistics are built on the belief that fundamentally there is only one circuit, namely straight from production to consumption. They measure what they can and in any case are descriptive of what ordinary people can recognise as buying and selling. In contrast Lonergan’s categories are analytic, so we need to develop different categories to research the statistics to underpin the narratives of where we are up to and what we are to be about. At the moment Lonergan’s analysis just provides what he called “rather convincing indicators”.[xix] Lacking statistically based narratives, Church commentators and others will find it difficult to produce decisive policy statements, suggest relevant programmes or support effective interventions. Other interests and motives will remain dominant. Fortunately the task is not merely academic, and given these pointers, it is now time to return to indicate some of the non-economic pre-conditions for managing an equitable economy, an economy that embeds justice in a way that reaches the parts that other versions of distributive justice cannot reach.

Towards a democratic economy

In Lonergan’s worldview, one of the conditions for establishing an equitable economy is that the teaching of a fuller understanding of the economy comes to inform the democratic actions of ordinary citizens in their everyday lives. Lonergan is not a friend to bureaucracy [xx] whether of the state or the international corporation. He argues instead that the radical re-distribution implied in the basic expansion comes about through citizens, including business people, acting on a critically realist understanding of how an economy works. There is a role then for a Church with a world-wide educational system in preparing the ground for the reception of a critically realist account of the economy, and here it can be noted that Lonergan wrote on education and schooling as well as the economy.

Human bias

The difficulties to be faced are not only intellectual. Implementation of a new economics will not be without problems. For those for whom all this talk of economics seems to leave faith and human weakness outside the window, Lonergan also has an understanding of ‘bias’, of our tendencies to limitation rather than transcendence. He points to those elements of individual and group behaviour that have formed the backdrop to much of the left-versus-right political-economic accusations. Groups exploit their positional situations to preserve their own advantage. Individuals, too, use their intelligence to maximize gains for themselves against the interests of others. In addition, there are the lacunae in our psychological make-ups that open us up to dysfunctional uses of power in advertising, in the board room or on the factory floor.[xxi] Finally, and perhaps most difficult to overcome, there is our pragmatic realism. The short-termism referred to by commentators on the City reflects our inability to see further than in front of our noses. A new economics requires the partnership of a renewed evangelisation.

A renewed evangelisation

Moments of heightened anxiety and crisis open people to look for solutions, to hear good news. And it is indeed true that the suffering servant can heal contemporary evils. But, if the proclamation of the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ is to be at the level of the crisis of our times, the Church needs to operate with theoretical understandings that can lift our contemporary, common sense grasp of how an economy works out of its current pitfalls. After all, it is when economies falter and fail that economics begins to rule our lives, and it is not only believers who want a world in which politics is not reduced to the economy (as in Bill Clinton’s famous phrase, “It’s the economy stupid.”) It is not only Christians who want their family life to be free of impoverishment and the insistent and incessant need to ‘make a living’. It is not only Catholics who see the raison d’etre of humanity as something more than just economics, and who want to live without the ups and downs of the economy being the central focus of our understanding of what it is to be human.

Peter Corbishley lives and works mainly in the Third Sector in the East End of London. He holds a Licentiate in Philosophy from the Gregorian University and degrees in Sociology and Theology. Further details can be found on www.english-english.co.ukIf anyone has the money or the time to make co-operative housing (and other forms of resident-controlled housing) part of the 2012 legacy in East London please e-mail[email protected]

[i] P82 Lonergan, BJF (1999) Macroeconomic dynamics : an essay in circulation analysis University of Toronto Press

[ii] The ignorance extends to our choice of politicians cf Alesina, A, Roubini, N, Cohen, G Political cycles and the Macroeconomy Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press. Nouriel Roubini has been predicting the current crisis for a number of years.Cf. www.nytimes.com/2008/08/17/magazine/17pessimist-t.html

[iii] Martin, S (2008) Healing and creativity in economic ethic : the contribution of Bernard Lonergan’s economic thought to catholic social teaching University Press of America

[iv] Cf Longley, C (23rd August 2008) ‘An acceptable face of capitalism’ The Tablet p10-11. Here organisations with different interpretations of how to run our economy are both said to claim the mantle of the Church’s Social Teaching. Then, as happens in this article, the real argument easily shifts both from the economy and the Church’s teaching to a left-right political analysis.

[v] Cf Shiller, RJ (2008) The subprime solution Princeton

[vi] A sympathetic account this period of Lonergan’s life, including of his economics, can be found in Matthews, WA (2005) Lonergan’s quest : a study in desire in the authoring of Insight University of Toronto Press cf pp109-131. For the his economic writing up to the end of World War II see Lonergan, BJF (1998) For a new political economy University of Toronto Press

[vii] Soros, G (2008) The New paradigm for financial markets : the credit crisis of 2008 and what it means London : Public Affairs Ltd

[viii] For a diagrammatic representation please see Appendix 1

[ix]We need to distinguish two different kinds of technological investment. To give examples from the UK, there is, firstly, the kind of technology currently called ‘high tech’, although the phrase ‘high tech’ covers a number of distinct technologies .In an actual modern economy, therefore, there may be surplus expansion taking place with several different technologies. In contrast, investment in the basic expansion is spent on technologies that expand consumption directly. It may be that the UK has not recently invested in this kind of technology, but instead bought in ‘high tech’ consumption goods from abroad, eg. Korea or Japan. The lack of investment in the second kind of technology probably underlies the common belief in the decline of UK manufacturing.

[x] The fact that the economic model of education can lead to a reductionist playing down of a genuine humanistic understanding of the benefits of education, as may well be the case currently in the UK, does not take away from the distinction between basic and surplus circuits in the economy.

[xi] Leather manufacturing has been taken as an example because of my own experience of working with local CMT companies and support agencies in the 1970’s in Tower Hamlets, in the East End of London - businesses which now only exist if they produce for the expensive end of the market. Tower Hamlets, itself, is a telling comment on our inability to deal with poverty on a national let alone an international scale. An area north east of St Dunstan’s in Stepney, close to where I live, was chosen as the location for a neighbourhood based poverty reduction programme of the early New Labour government. Ironically the programme area substantially overlaps with an area mapped out as “vicious and semi-criminal” or as experiencing “chronic want” nearly 150 years ago.Cf 1889-99 map http://booth.lse.ac.uk/cgi-bin/do.pl?sub=view_booth_and_barth.Relative poverty seems to have a persistent geographical element to it.

[xii] The clothing industry in Tower Hamlets now remains as an “import-modify-export with a made in the UK label” industry, but Lonergan also uses clothing as an example. The question remains as to whether real investment in computerising the industry would have retained rather more employment in the local area.

[xiii] With the clothing industry we have already noted the one-to-one relation of cotton and coat, as well as the one-to-many of a single knife or loom to many coats. One to many relations of a loom, say, to a line of production can be expressed mathematically as point to line relationships, then machines that make the looms are in a point-to-surface relationship with a standard of living, and so on through point-to-volume into ‘n’ dimensions to be handled, Lonergan believed, through matrix algebra. Finally, the distinction between basic and surplus is not through classification of objects or activities as either basic or circuit. The distinction and the hierarchical relationships are explanatory and functional. The same object or activity can at one time be part of the basic circuit and at another part of the surplus. Electricity can be used to power the CERN experiment or light bulbs in a house. The same make of light bulb can be used in an office in a factory, in a shop or at home.

[xiv] P82 Lonergan, BJF (1999) op cit.

[xv] P81-2 Lonergan (1999) op cit. It may well be that what has happened in the UK is that the surplus income available for investment from the surplus expansion has been spent through raising the standard of living directly, for example by taking out credit against ‘privately owned’ but mortgaged houses.

[xvi] Written in 1944, P153 Lonergan, BJF (1999) op cit.

[xvii] Redistribution here does not mean giving from the rich to the poor, but models how financial institutions redistribute money between basic and surplus circuits.

[xviii] ‘E’ street where ‘E’ stands for entrepreneur. The name ‘E’ street is my illustration, not Lonergan’s. However, he does suggest that investment cycles that produce a fundamental transformation of the capital equipment of an economy include long-term accelerations that prepare for the fundamental transformation, and long term accelerations that realise the benefits of that fundamental transformation. Cf p162 Lonergan (1999) op cit. If Lonergan is correct then in a modern complex economies there is a third street of entrepreunerial activity that continues to run alongside the High Street and Threadneedle Street in the City, even if the rate of activity in ‘E’ street varies over time.

[xix] p72 Lonergan (1999) op cit.

[xx] Interestingly his critical comments on bureaucracy come first in his writings on education cf pp60-61 Lonergan, BJF (1993) Topics in Education University of Toronto Press lectures delivered in 1959. De Neeve, E (2008) Decoding the economy : understanding change with Bernard Lonergan Thomas More Institute Papers/08 p131 notes that “More than half of all international trade takes place within global enterprises. This means that sales are not organised through market exchanges, but through a command system of accounting prices decided within the corporation.” After going on to comment on the international financial and currency transfers that are part of the business of multinational corporations and international fund investors, she concludes this paragraph by saying, almost prophetically as regards the present situation, that “Regulating international financial transaction equitably remains an issue for world financial stability.”

[xxi] Cf for example Zimbardo, P (2007) The Lucifer effect (London : Rider) on Abu Ghraib

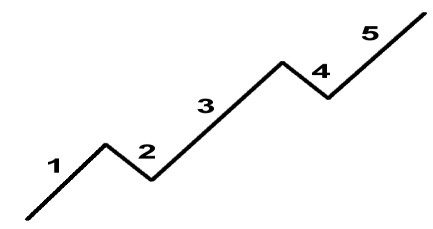

Appendix 1

The ‘s’ curve

The following diagram describes a series of 2 booms and 2 slumps in a modern economy. The 5 phases do not form a cycle. Living standards do rise across time, but are inequitably distributed.

In contrast Lonergan’s model of the economy enables him to smooth the sequence of booms and slumps into a single cycle based on the ‘s’ or ‘sigmoid’ curve. The model has 5 phases (not marked here) where phase 5 at the top of the curve is equal to phase 1 at the bottom of the curve but clearly at a higher standard of living as indicated by the greater quantity of goods available in the economy. Now the redistributional function equitably switches the focus of investment from surplus expansion to basic expansion over the longer term. In addition there is a single identifiable cycle. [xxi]

Further Reading

The Lonergan titles are more readily available on www.amazon.com than on the UK site.

Burley, P (1989) A von Neumann Representation of Lonergan’s Production Model Economic Systems Research 1:3 317-30

De Neeve, E (2008) Decoding the economy : understanding change with Bernard Lonergan Thomas More Institute Papers/08

http://www.thomasmore.qc.ca/tmi.html

Lonergan, BJF (1998) For a new political economy University of Toronto Press

Lonergan, BJF (1999) Macroeconomic dynamics : an essay in circulation analysis University of Toronto Press

Martin, SL (2008) Healing and creativity in economics the contribution of Bernard Lonergan’s economic thought to Catholic social teaching University Press of America

Matthews, WA (2005) Lonergan’s quest : a study in desire in the authoring of Insight University of Toronto Press cf pp109-131

McShane, P (1998) Economics for everyone Das Jus Kapital Axial Press

http://www.lonergan.org/axialpress/index.html