Reviewing the fourth and final part of BBC1’s The Passion, Gerald O’Collins SJ examines how it handles what is perhaps its most difficult task – the portrayal of the Resurrection, and of the way in which the risen Jesus interacts with his still-not-wholly-comprehending disciples.

A barren, deserted landscape and then a glorious sunrise set the scene for the burial of Jesus and the appearances that follow his resurrection. New light and new life have come into the world and remain forever. This fourth episode in the BBC drama draws from the Gospels and imaginatively adds to the story.

When Joseph of Arimathea wants to bury Jesus, Pilate grants permission, but, uncharacteristically, does not seek any kickback. Instead, the Roman prefect puts the haunting question: “Sent by God, he let himself be crucified?”

We switch to the disciples and see them tormented by grief. James echoes Pilate by asking: “Do you think that God would let his only Son die like that?”

When Joseph of Arimathea buries Jesus, from inside the tomb the camera shows the great stone being rolled into place and viewers are plunged into darkness. We are left with a tragic sense of closure. As the wife of Caiaphas says to her husband, “it’s over. It’s all over thanks to you.” But Caiaphas is still troubled by what he has done. He angrily disowns his guilt: “Joseph accuses me of sending an innocent man to his death!” He insists: “Everything I have done, I have done for the good of our people.”

After the burial, Mary and Mary Magdalene will not leave the tomb. With her hand on the stone blocking the entrance, Mary turns to the camera and sorrowfully asks: “Where are his friends now?” The two women are then driven away by Temple guards who arrive to guard the tomb.

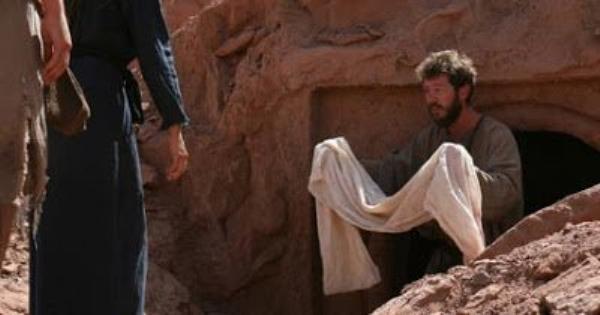

The film blends and adapts three Gospels to present the first Easter Sunday morning. When Mary Magdalene comes to the tomb and finds it open and empty, she runs to tell Peter and the beloved disciple and bring them to see the tomb. They too fail to find the body of Jesus, and Peter emerges carrying the grave cloths (John’s Gospel). The guards, who have gone to get some food, return and also discover the stone to be have been rolled away. They rush to tell Caiaphas that the body has disappeared and suggest that grave-robbers have been at work (Matthew). Back at the tomb Mary Magdalene becomes hysterical at the thought that the body has been stolen (John). Suddenly Jesus appears to her and, using words Luke puts in the mouth of two angels, asks: “Why do you look among the dead for someone who is living?” The film likewise follows Luke by having some male disciples dismiss Mary Magdalene’s news of the resurrection as self-delusion: “You wanted to see him.”

The Passion adds three more appearances of the risen Jesus. At Emmaus he breaks bread with the two disciples and they recognize him when he says: ‘This is the bread of life. This is my body given up for you. This is my blood poured out for you.’ We then see him appearing to the disciples back in Jerusalem. At the very end he meets Peter on the side of a pool in Jerusalem, where Peter is washing the feet of a disabled man. The script follows John’s Gospel when Jesus questions Peter about his love and commissions him for his coming ministry to the world.

To enhance the sense of a happy ending, Pilate and his wife ride out of Jerusalem and evidently expect advancement in the imperial service. The Emperor Tiberius has left the island of Capri and returned to Rome. Pilate remarks with satisfaction: “I served him well.” The film switches to the wife of Caiaphas who gives birth to a son. The high priest is overjoyed to have now an heir as well as two little daughters.

Dramatic licence shapes history. In fact, Pilate stayed on as prefect and was removed for misgovernment six years later. For someone who became high priest twelve years before Jesus’ crucifixion, Caiaphas is improbably young in the film and decked out with an even younger wife. They both look wonderful on the screen. This is the first Jesus film in which I have seen the wife of Caiaphas. Pilate’s wife enjoys at least a mention in one of the passion narratives (Matthew 27: 19).

The Passion struggles to be historically authentic and also with the challenge of representing the risen body of Jesus. The words of Mary Magdalene catch a sense of his transformation: “It wasn’t him. But it was.” He was and is the same Jesus, but now gloriously different through rising from the dead. The film ends with Jesus looking at Peter with love and then walking away down a street in Jerusalem. Those who pass by do not notice or interact with him. The risen Jesus is truly there in their midst, but only those who love him and follow him can recognize him.

Gerald O’Collins SJ is currently teaching Theology at St Mary’s University College, Twickenham. He is the author of many books, including Easter Faith: Believing in the Risen Jesus (DLT, 2003), Jesus Risen: An Historical, Fundamental and Systematic Examination of Christ's Resurrection (Paulist Press, 1987) and Jesus Our Redeemer: A Christian Approach to Salvation (OUP, 2007).

![]() St Mary's University

St Mary's University

![]() Easter Faith: Believing in the Risen Jesus

Easter Faith: Believing in the Risen Jesus

![]() Jesus Risen: An Historical, Fundamental and Systematic Examination of Christ's Resurrection

Jesus Risen: An Historical, Fundamental and Systematic Examination of Christ's Resurrection

![]() Jesus Our Redeemer: A Christian Approach to Salvation

Jesus Our Redeemer: A Christian Approach to Salvation

![]() Visit the BBC’s The Passion web site

Visit the BBC’s The Passion web site

![]() Watch this episode on BBC iPlayer (available until 30 March)

Watch this episode on BBC iPlayer (available until 30 March)